Abstract

The prolific (but rarely remembered) Victorian playwright George Dibdin Pitt wrote the first Sweeney Todd dramatization in 1847 for the Britannia in London’s East End, tailoring his melodrama for the theater’s particular audience and the acting company’s individual talents. Not published until 1883 in Dick’s Standard Plays (as Sweeney Todd: The Barber of Fleet Street, or The String of Pearls), the printed play differs significantly from Dibdin Pitt’s original, which was initially performed on 1 March 1847 as The String of Pearls, or The Fiend of Fleet Street. Scholars who rely on the 1883 Sweeney Todd to discuss the 1847 melodrama are in many respects talking about a different play. One major difference involves a main character who appears only in the 1847 version. In the 1846-47 novel, a faithful dog named Hector is important to the plot; in the 1847 play, he is transformed into a major heroic character who foils the play’s villains — no longer a dog, but a deaf-mute black boy, a former slave from British Honduras who loyally continues to serve his former owner and current employer out of love and gratitude for his freedom. By including this character, Dibdin Pitt takes an identifiably abolitionist stance, working through what was still England’s strong sense of moral achievement in abolishing slavery and still strong sense of purpose in working to end slavery in the United States. But by 1883, in regards to race and colonialism, the cultural work of Dibdin Pitt’s play without Hector operates through an unthinking backdrop of the Empire’s power and the status quo of racial hierarchy.

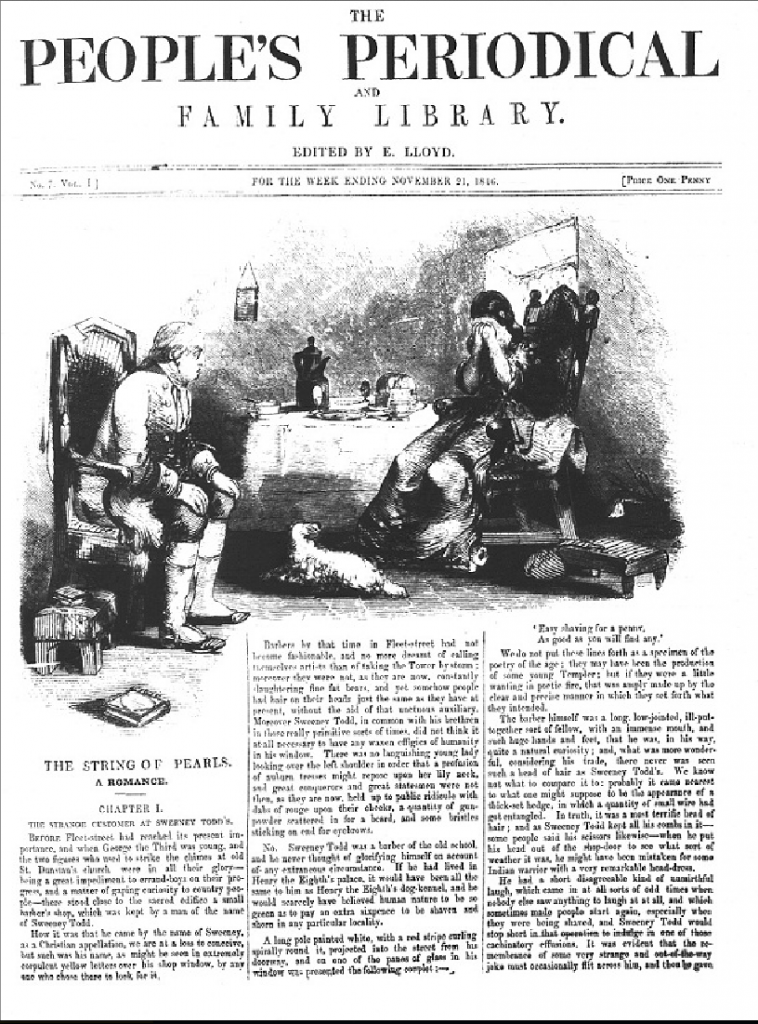

Like Dracula and Frankenstein, Sweeney Todd is what Paul Davis calls a “culture text,” one we recognize even without having read the original work. Besides the acclaimed Stephen Sondheim musical Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of ![]() Fleet Street (1979), Sweeney Todd has been made into at least four films, two TV movies, music hall ditties, radio plays, and a ballet (Mack Sweeney xxxi-xxxvii). The myth of Sweeney Todd is so powerful that many people claim in print (and particularly on fan websites) that the story was based on an actual case of murder and cannibalism, despite the fact that there is no evidence of this—at least, not on Fleet Street, not in London.[1] Yet unlike the masterpieces by Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker, the novel that gave birth to this particular hideous progeny is little studied. The lack of academic interest may be because—the compelling and wildly popular bogey-man (or bogey-couple) notwithstanding—the novel relies largely on stock characters embroiled in a disjointed plot. Several serial episodes lead nowhere, characters are left dangling, and the whole thing ends abruptly. Its beginnings are so humble that no one even knows for sure who wrote it. What is certain is that The String of Pearls: A Romance came out anonymously in eighteen weekly installments, starting in the issue for the week ending on Saturday, 21 November 1846, and concluding in the issue for the week ending on Saturday, 28 March 1847. The tale filled slender columns alongside funny sketches, rousing travel narratives, and recipes for rat poison in the otherwise insignificant People’s Periodical and Family Library. (See Fig. 1.)

Fleet Street (1979), Sweeney Todd has been made into at least four films, two TV movies, music hall ditties, radio plays, and a ballet (Mack Sweeney xxxi-xxxvii). The myth of Sweeney Todd is so powerful that many people claim in print (and particularly on fan websites) that the story was based on an actual case of murder and cannibalism, despite the fact that there is no evidence of this—at least, not on Fleet Street, not in London.[1] Yet unlike the masterpieces by Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker, the novel that gave birth to this particular hideous progeny is little studied. The lack of academic interest may be because—the compelling and wildly popular bogey-man (or bogey-couple) notwithstanding—the novel relies largely on stock characters embroiled in a disjointed plot. Several serial episodes lead nowhere, characters are left dangling, and the whole thing ends abruptly. Its beginnings are so humble that no one even knows for sure who wrote it. What is certain is that The String of Pearls: A Romance came out anonymously in eighteen weekly installments, starting in the issue for the week ending on Saturday, 21 November 1846, and concluding in the issue for the week ending on Saturday, 28 March 1847. The tale filled slender columns alongside funny sketches, rousing travel narratives, and recipes for rat poison in the otherwise insignificant People’s Periodical and Family Library. (See Fig. 1.)

Figure 1: First installment of _The String of Pearls: A Romance_ (Louisiana State University Middleton Library. Used with permission)

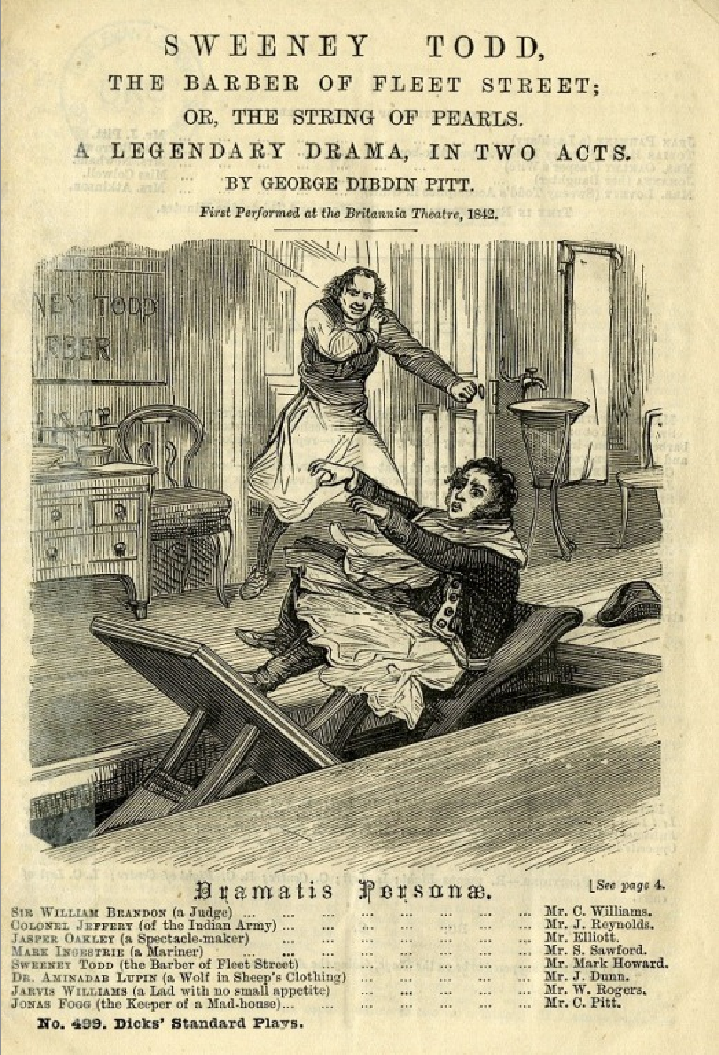

Figure 2: Title page of _Sweeney Todd, or The String of Pearls_, Dick’s Standard Plays No. 499 (Theatre Collections, Templeman Library, University of Kent, UK. Used with permission)

When George Dibdin Pitt died in 1855, the theatrical newspaper The Era ran an obituary claiming that he had written “700 melo-dramas, farces, and extravaganzas” in his career (Moore 299). As vast and perhaps unlikely as that number seems, at least 250 are known. If The Era’s figure is correct, Dibdin Pitt is arguably the most prolific playwright in British history. He was also enormously popular in his own day. By 1842, almost all the important minor theaters in London had mounted at least one of his plays, and several had produced many, many more. (A “minor” theater was any playhouse that did not have a Royal Patent to perform drama. In other words, virtually every theater in London except for Drury Lane and Covent Garden—no matter how fashionable or successful—was a “minor theater.”) His domestic melodrama Susan Hopley, the Vicissitudes of a Servant Girl (1841) was so popular that it was performed over 100 times the first season and another 50 the next, attracting droves of servant girls nightly (Brenna Theatre 33). Unlike the vast majority of Victorian plays, Susan Hopley was ultimately published in two different editions—Lacy’s Acting Editions (1866) and Dick’s Standard Plays (1883)—a testament to its enduring fame and significance. At least fourteen of Dibdin Pitt’s plays were printed in the nineteenth century, an enviable accomplishment for any playwright. Out of all this prodigious output, Pitt is now remembered solely for his play Sweeney Todd.

Like the novel, Dibdin Pitt’s adaptation was at first called The String of Pearls, with the added subtitle “or, The Fiend of Fleet Street.” It, too, was aimed at a working-class audience. Dibdin Pitt wrote it for production at the ![]() Britannia Saloon, also known as the “The People’s Theatre.” The Britannia was a popular

Britannia Saloon, also known as the “The People’s Theatre.” The Britannia was a popular ![]() East End playhouse praised by Charles Dickens in “The Amusements of the People” in 1850 and again in “Two Views of a Cheap Theatre” in 1860.[2] George Bernard Shaw extolled the theater and its extraordinary actor-manager, Sarah Lane, in his classic 1897 essay “The Drama in Hoxton,” often read now by students as an example of Victorian dramatic criticism. Dibdin Pitt was the staff playwright at the Britannia from about 1844 to about 1851, spitting out a new play every two weeks. After its initial two-week run, The String of Pearls appeared in various forms throughout the rest of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth.[3] But it was not until 1883, thirty-six years after its premiere and twenty-eight years after the playwright’s death, that Pitt’s melodrama was published under the name of Sweeney Todd, the Barber of Fleet Street, or The String of Pearls in Dick’s Standard Plays.

East End playhouse praised by Charles Dickens in “The Amusements of the People” in 1850 and again in “Two Views of a Cheap Theatre” in 1860.[2] George Bernard Shaw extolled the theater and its extraordinary actor-manager, Sarah Lane, in his classic 1897 essay “The Drama in Hoxton,” often read now by students as an example of Victorian dramatic criticism. Dibdin Pitt was the staff playwright at the Britannia from about 1844 to about 1851, spitting out a new play every two weeks. After its initial two-week run, The String of Pearls appeared in various forms throughout the rest of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth.[3] But it was not until 1883, thirty-six years after its premiere and twenty-eight years after the playwright’s death, that Pitt’s melodrama was published under the name of Sweeney Todd, the Barber of Fleet Street, or The String of Pearls in Dick’s Standard Plays.

This published version of Pitt’s play differs significantly from Pitt’s original script as it was submitted for licensing on 15 February 1847 and archived in the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays Collection. The Theatrical Licensing Act of 1737 required scripts to be submitted to the Lord Chamberlain’s office for licensing before they could be performed on stage. Licenses could be denied for several reasons, including violent or subversive content. Because all plays to be performed on the public stage in Great Britain from 1737 until 1968 were submitted for licensing, the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays collection (1824-1968) in the ![]() British Library constitutes an extraordinary resource for anyone interested in British drama.[4] Even when a play was eventually published, as is the case with Sweeney Todd, a comparison to the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays manuscript is extremely instructive. The licensing version of Dibdin Pitt’s 1847 Sweeney Todd varies so much from the published version that it is almost a different play. The Lord Chamberlain’s Plays text was published for the first time in 2012 in Nineteenth-Century Theatre and Film 38.1.[5]

British Library constitutes an extraordinary resource for anyone interested in British drama.[4] Even when a play was eventually published, as is the case with Sweeney Todd, a comparison to the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays manuscript is extremely instructive. The licensing version of Dibdin Pitt’s 1847 Sweeney Todd varies so much from the published version that it is almost a different play. The Lord Chamberlain’s Plays text was published for the first time in 2012 in Nineteenth-Century Theatre and Film 38.1.[5]

Before discussing the variations between the play as it was initially performed in 1847 and its appearance in print in 1883, we need to consider the changes Dibdin Pitt made to create a successful melodrama out of the novel in the first place. Some modifications are typical of Victorian page-to-stage adaptation. For example, the play ends quite differently, as is to be expected since it premiered on 1 March 1847, more than a fortnight before the novel’s concluding installment for the week ending 20 March 1847. This occurrence was commonplace in the Victorian period because there were no copyright protections for authors of novels in regard to theatrical adaptation. Oliver Twist is the most famous example. The final number of Oliver Twist appeared in Bentley’s Miscellany in April 1839; George Almar’s Oliver Twist: A Serio-Comic Burletta premiered at the Surrey Theatre in the autumn of 1838. Watching a performance, Dickens was so humiliated that during the first scene he lay down in the corner of his box and hid there until the final curtain (Cox 121).

The phenomenon in which a novel is adapted for multiple stage productions before the author has completed publishing or even writing the book is analogous to international reprinting without copyright protection. The proliferation of such pirated versions of an original imaginative work was the norm at this historical moment, as Meredith McGill explains in American Literature and the Culture of Reprinting, 1834-1853. Although authors and publishers lambasted the practice that resulted in loss of revenue and a perceived bastardization of their aesthetic vision, the widespread productions also had beneficial effects. Very often, stage productions insured a novel’s subsequently wider distribution in print; theater audiences included the semiliterate and the illiterate, a far broader population even than the penny press could serve. Every neighborhood had its own theater, so the same novel could be dramatized by different playwrights for theaters all over London and the provinces in near simultaneity, each with a different take on the adaptation, each tailored to appeal to a specific audience, spreading the novel’s attractions even further. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club appeared serially from April 1836 to November 1837, at which point it first appeared in volume form. By December 1838, Pickwick had been performed in at least 26 separate adaptations at minor London theaters—and this does not take into account productions in the provinces or abroad. After the Oliver Twist mortification, Dickens’s strategy was to work with playwrights to try to influence the way his work was adapted, to extract payment for officially sanctioned adaptations, and to write books (in particular his Christmas books) with future staging in mind (Allingham Victorian Web). Just as J. K. Rowling composed the later Harry Potter books with cinematic effect as part of her plan, so some Victorian novelists wrote thinking about theatrical effect. In other words, the Victorian culture of performance affected the Victorian novelist’s aesthetic vision.

Another typical way in which authors and illustrators helped to shape how Victorian stage adaptations would ultimately interpret their popular novels is the use of Pictures or Tableaux. These are moments in which the action freezes for a moment as the actors assemble themselves into postures that the audience will recognize as exact replicas of illustrations from the fiction they already know and like. The satisfaction of seeing the familiar pictures realized on stage was a genuine pleasure for Victorian theater-goers and is still available to modern audiences in such plays as Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park with George.[6] Many twentieth-century film adaptations of Dickens do the same; for example, David Lean’s Oliver Twist (1948) sets up shots to realize Cruikshank’s original illustrations (Joseph 18), a direct inheritance from earlier film versions that closely imitated Victorian stage productions that already adhered closely to Dickens’s and Cruikshank’s vision. In the 1847 The String of Pearls, Dibdin Pitt identifies Pictures in staging that are realized from the novel’s illustrations (Weltman Sweeney 43-45, 65-66).

Music was another traditional component of melodrama that Dibdin Pitt employed in adapting The String of Pearls. Before the 1843 Theater Regulation Act legalized the performance of “legitimate” or non-musical plays outside the “major” or patent theatres such as ![]() Drury Lane, minor theaters needed to include at least five songs in any dramatic presentation or risk incurring a steep fine. This protected the patent theaters’ monopoly on drama, which generically is not a musical entertainment and which traditionally held a higher place in theatrical hierarchy. In the eighteenth century, British theater imported the French genre of melo-drame, or melody-drama, in which musical accompaniment helped to guide audiences’ emotions in response to the play’s action. Because this could be marketed as musical entertainment, it was a perfect medium to dodge the prohibition on dramatic performances in venues other than the major theaters. By 1843, these distinctions had stopped making sense since musical entertainments were so popular that the patent theaters were performing them as well, and the minor theaters had long since successfully circumvented the law by producing even Shakespeare and other classic dramatists by adding music or other gimmicks, such as Astley’s Circus’s performances of Shakespeare on horseback. (Richard III was a natural.) But after the 1843 Theatre Regulation Act was passed, even though songs were no longer legally required for the production of a melodrama, audiences enjoyed and expected the songs and musical underscoring that remained a significant aspect of melodrama’s generic conventions. Dibdin Pitt incorporated several songs into his melodrama The String of Pearls. The lyrics of only one song—a chorus singing about the tastiness of Lovett’s meat pies—are included in the script as the Act 2 opening number, but two more songs (sung by favorite Britannia actors) are advertised on the playbill for the 1 March 1847 premiere.[7] There may well have been more songs in the production; certainly the script identifies several moments of musical underscoring for dramatic effect.

Drury Lane, minor theaters needed to include at least five songs in any dramatic presentation or risk incurring a steep fine. This protected the patent theaters’ monopoly on drama, which generically is not a musical entertainment and which traditionally held a higher place in theatrical hierarchy. In the eighteenth century, British theater imported the French genre of melo-drame, or melody-drama, in which musical accompaniment helped to guide audiences’ emotions in response to the play’s action. Because this could be marketed as musical entertainment, it was a perfect medium to dodge the prohibition on dramatic performances in venues other than the major theaters. By 1843, these distinctions had stopped making sense since musical entertainments were so popular that the patent theaters were performing them as well, and the minor theaters had long since successfully circumvented the law by producing even Shakespeare and other classic dramatists by adding music or other gimmicks, such as Astley’s Circus’s performances of Shakespeare on horseback. (Richard III was a natural.) But after the 1843 Theatre Regulation Act was passed, even though songs were no longer legally required for the production of a melodrama, audiences enjoyed and expected the songs and musical underscoring that remained a significant aspect of melodrama’s generic conventions. Dibdin Pitt incorporated several songs into his melodrama The String of Pearls. The lyrics of only one song—a chorus singing about the tastiness of Lovett’s meat pies—are included in the script as the Act 2 opening number, but two more songs (sung by favorite Britannia actors) are advertised on the playbill for the 1 March 1847 premiere.[7] There may well have been more songs in the production; certainly the script identifies several moments of musical underscoring for dramatic effect.

Many of Pitt’s changes from novel to play remained an important part of Sweeney Todd in later stage and film adaptations and for the novel’s rewritings, expansions, and republications. One addition that has remained popular is the notion that the tale is “founded on fact,” as Britannia advertised on the 1 March 1847 playbill. But Dibdin Pitt’s 1847 text makes another important change from the novel that does not appear in later adaptations, not even in his own play as it was eventually published in 1883, involving the character from the novel named Hector. As I have written elsewhere, this character’s remarkable transformation from novel to play—and subsequent disappearance from the later version of the play—rewards particularly close textual analysis and comment for what it reveals about the moment in which it was performed and how that context affected performance (Weltman Sweeney 1-22).

In the novel, Hector is a faithful dog who leads authorities to Todd’s tonsorial parlor after his master, a sailor named Thornhill, enters for a haircut and shave, but never reemerges. The dog bravely swims to a large vessel docked at port, carrying his master’s hat in his mouth, to establish that there has been a murder and to prompt investigation. In the play, Thornhill’s loyal friend is still named Hector, but he is now a human being, a “black boy,” as the list of Characters identifies him (31). He behaves in many ways exactly as Hector the dog does. In the novel, the frantic pet pushes into Todd’s shop where, scratching at a cupboard door, he recovers his dead master’s hat. The play’s Hector does likewise; both ward off Todd as they obtain evidence, one with his teeth, the other with his Carib knife. The boy is so like the dog that he even swims out to the ship with his master’s hat in his mouth.[8] Both attempt wordlessly to convince Thornhill’s friends to come ashore. The dog howls dolefully; the deaf-mute boy makes signs. Both Hectors resort to pulling on the captain’s coat before Thornhill’s friends figure out what to do.

It may seem that the move from dog to black servant is straightforward racism. Colonialist literature includes a long tradition of muzzled black characters, as Gayatri Spivak points out. Defoe’s silent Friday from Robinson Crusoe was a staple of the Victorian stage.[9] Likewise, animal imagery is frequently invoked in depictions of blackness, with Shakespeare’s Othello a favorite among the Victorians. But it is also important to remember that the mute is a stock character in melodrama, allowing for large pantomime gestures, as Peter Brooks and others have explained. The play’s representation of Hector is both racist and traditional to the genre of melodrama, but there are other things—having to do with empire, gender, and abolition—at work here.

Hector hails simultaneously from many of the domains of England’s colonial sway: he is purchased as a baby in ![]() Honduras, dresses in Nankeen clothes, and brandishes a Carib knife. Hector was born a slave in what would later be formalized as a British colony and in a place that clearly suggests his African ancestry (Girot 73). Yet he is also from

Honduras, dresses in Nankeen clothes, and brandishes a Carib knife. Hector was born a slave in what would later be formalized as a British colony and in a place that clearly suggests his African ancestry (Girot 73). Yet he is also from ![]() India: shortly before stabbing Hector’s master Thornhill, Sweeney Todd says, “You have lately come from India Sir, by the appearance of your attendant” (36). In a successful ruse to expose the preacher Lupin, who womanizes throughout the play, Hector tricks the hypocrite by donning a dress and impersonating the minister’s abandoned “black wife” (59). Lupin admits that, when a missionary “in the West Indies and Africa, I might have tried to reclaim such a one. I despised her not because she was a Black. I clasped her to my bosom in the faith” (59). The missionary here conflates the West Indies and Africa, distant areas of British colonial power, suddenly interchangeable. The game is up for the predatory Lupin, who had spent most of the play trying to get women to attend his evangelical “love meetings” (58).

India: shortly before stabbing Hector’s master Thornhill, Sweeney Todd says, “You have lately come from India Sir, by the appearance of your attendant” (36). In a successful ruse to expose the preacher Lupin, who womanizes throughout the play, Hector tricks the hypocrite by donning a dress and impersonating the minister’s abandoned “black wife” (59). Lupin admits that, when a missionary “in the West Indies and Africa, I might have tried to reclaim such a one. I despised her not because she was a Black. I clasped her to my bosom in the faith” (59). The missionary here conflates the West Indies and Africa, distant areas of British colonial power, suddenly interchangeable. The game is up for the predatory Lupin, who had spent most of the play trying to get women to attend his evangelical “love meetings” (58).

Part of what is happening in this scene is surely the racist humor involved in the notion that any black teenage boy could convincingly play any black woman well enough to trick her white husband, which relies on the racist idea that everyone of a particular race looks alike. But there is even more going on. Hector is not only human, not only a cross-dressed black boy, not only the vehicle for racist humor, but also the figure of England’s seemingly universal colonial reach, the soothingly contented and faithful former slave of Britain. And there is an additional complication: the deaf-mute Honduran/African/Caribbean/Chinese/Indian boy impersonating Lupin’s wife from Africa or the West Indies was played by a woman (a typical casting choice for mutes and for adolescent boys in Victorian melodrama). In other words, playgoers in March 1847, would have seen with triple vision the pan-Other boy Hector, whom they simultaneously recognized as the courageous dog from the popular novel and the actress-dancer Mrs. Roby featured on the playbill from the Britannia and reviewed in the Theatrical Times (Weltman Sweeney 26, 16).

Even more than in the novel, the play’s Hector is a hero, heralded on the playbill equally in prominence to the young romantic lead, Thornhill, and the villain, Sweeney Todd (Weltman Sweeney 26). In addition to notifying the authorities of Thornhill’s plight, the human Hector saves Thornhill’s life and helps to overcome not one but two scoundrels, Lupin and Todd. In these achievements, he surpasses the dog Hector, who fails to save the life of his Thornhill and plays no part in Lupin’s disgrace. Dibdin Pitt’s play creates Hector’s triumphs and represents him positively. Thornhill describes the deaf-mute as having “intelligence beyond that of thousands possessing every faculty” (76); the boy “discovered, planned, and assisted [Thornhill’s] escape” (76). He helps indict Sweeney Todd because, while Todd’s apprentice Tobias makes a deposition about the villainy he witnessed in during his employment by Todd, it is “that dumb youth” who “by signs has confirmed all” (80).

Dibdin Pitt wrote several other plays for the Britannia at this time that demonstrate his interest in valiant black characters, so this characterization of Hector as hero is not a fluke. The most striking example is his 1846 play Toussaint L’Ouverture or the Black Spartacus, in which L’Ouverture courageously leads the Haitian rebellion (while also nobly saving the life of his white former master).[10] In making Hector both a hero and a former slave, Pitt comments on the positive outcome of abolition in Britain and British territories in 1833. The issue was particularly topical in the months just before and while Dibdin Pitt must have been writing the play. Thomas Clarkson, the great abolitionist, died and was buried in October 1846; his years of anti-slavery agitation were described in papers and magazines for months afterward. In the very weeks that Dibdin Pitt was writing and the Britannia performing The String of Pearls, Frederick Douglas—often compared in the press to Tousaint L’Ouverture—was concluding his 20-month lecture tour of Great Britain, during which he raised sufficient funds to inaugurate the North Star, his abolitionist newspaper.

The initial scene in which Hector enters the action addresses the issue of slavery and abolition head on:

Colonel: A sharp, clean lad that! Where did you pick him up?

Thornhill: I bought him at Honduras, do not look surprised. I did indeed buy him, he was a mere infant then, and to my surprise, after his Mother’s death, I discovered that he was deaf and dumb.

Colonel: Is it possible! And yet so intelligent.

Thornhill: On my return to England I gave him his freedom, as I had at first intended, Indeed I had no right to make a slave of him here or abroad; you see he knows by the motion of my lips, that I am speaking of him and freedom. Music, Hector expresses gratitude, kneels to Thornhill, embraces his knees and kisses his hand. (33)

Because the play (like the novel) is set in 1785, Thornhill’s reply, that he “had no right to make a slave of him here or abroad” suggests that this 1847 melodrama continued to do the ideological work of abolition fourteen years after slavery was abolished in England (and, of course, in British Honduras). This dialogue indicates that Pitt expects the working-class audience at the Britannia to agree that Thornhill had no right to make a slave of Hector, not even when it was legal, as it would have been in the play’s 18th-century setting.

The passage also supports the view of the British tar as the champion of liberty, a dogma expressed in many nautical melodramas (Waters 133) and satirized by Gilbert and Sullivan in H. M. S. Pinafore (Williams 104-114).[11] The exchange ends with quintessentially melodramatic staging. Music, a basic generic fundamental of melodrama, manipulates the audience’s emotional response to the word “freedom,” while the black servant silently expresses his thanks to his white master, demonstrating it in big gestures: kneeling, embracing his knees, and kissing his hand. This melodramatic action assures the audience that the former slave is grateful for liberty, bears no grudge about the past, and voluntarily continues to serve out of devotion. The kneeling posture conjures the famous abolitionist emblem, on which a black man kneels in supplication, encircled by the words, “Am I not a Man and a Brother?”

A comparison between the 1847 play and its 1883 version published in Dick’s Standard Plays provides further evidence that Hector’s metamorphosis (from a dog in the novel into a positively depicted former slave in the play) comments on abolition. The character evaporates almost completely in the 1883 play. No Hector is included in the Dramatis Personae. But two traces of a pre-existing Hector remain. First Todd’s apprentice Tobias looks out the window of the barber shop and expresses wonder that the sailor Thornhill’s black servant is still out there; Toby is surprised because he incorrectly assumes that Thornhill has already left the shop, shaved. This servant never speaks or even appears on stage, has no bearing on the plot, and never before or after is mentioned in the dialogue. There is no reason for his race to be identified; plot-wise, the comment about the servant functions merely to notify the audience of something suspicious, building tension. Second, the hypocritical preacher Lupin receives his retribution when his real black wife and children enter the scene to chase him around in a bit of comic stage business. The effect is far more racist than in the play as Dibdin Pitt originally wrote it, in which the humor is produced by Hector’s clever duping of Lupin, not from watching the wronged wife and children try to beat up their deceitful husband and father. Such gratuitous racism in a play without Hector suggests a cultural shift. In 1847, Dibdin Pitt’s play as performed at the Britannia explores England’s satisfaction in having abolished slavery and determination to end slavery in the United States. But by 1883, twenty-eight years after Dibdin Pitt’s death, the ideological work of his play as it was ultimately published operates in a milieu of the Empire’s ever-growing power and the status quo of racial hierarchy, with no challenge to it and no assumption that those who might perform the published play would disagree.[12] Although Victorian melodrama, generally understood as a working-class genre, lends itself to cultural critique, it clearly also accommodates conservative points of view.

Regardless of who wrote the novel The String of Pearls or what might be its literary worth, it has generated over sixteen decades—and counting—of enthusiastic stage adaptation, re-novelization, and re-adaptation to stage and screen. This ongoing process began with the successful performance on 1 March 1847 of Dibdin Pitt’s dramatization, and it is George Dibdin Pitt whose name was first attached to Sweeney Todd. One aspect of the melodrama’s appeal to the 1847 audiences may have been Dibdin Pitt’s insertion of an abolitionist element found neither in the novel nor in later versions of the play, not even as it was ultimately published in 1883, many years after its premier. That the play could modulate to include an important current issue testifies to the flexibility of Victorian melodrama, a genre that—as David Mayer has pointed out—was always “responsive to immediate social circumstances and concerns” (146). Of course, this is still true of melodrama and still true of Sweeney Todd. Sondheim’s often revived 1979 Broadway musical speaks powerfully as a text of social protest, particularly class criticism. Like the 1973 non-musical melodrama adaptation of Sweeney Todd by Christopher Bond that inspired Sondheim, the Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd (and the 2007 Tim Burton movie musical based on it) invests its title character with a fierce revenge motive, transforming the pure villain of earlier incarnations into a sympathetic anti-hero. Todd’s murders are almost ritualized retribution against the corrupt social institutions and rigid class hierarchy that manipulated and destroyed his family. Resonating with post-Watergate mistrust in authority and (in the decades since) with recurring topical worries about serial murder and an adulterated food supply, Sondheim’s musical version of Sweeney Todd continues to respond to contemporary anxieties, as the tale will surely go on doing in its future iterations.

published August 2013

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Weltman, Sharon Aronofsky. “1847: Sweeney Todd and Abolition.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Allingham, Phillip. “Dramatic Adaptations of Dickens’s Novels.” Victorian Web. http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/dickens/pva/pva228.html. Web. 10 July 2013.

Bratton, Jacqueline. Acts of Supremacy: The British Empire and the Stage, 1790-1930. Manchester UP, 1991. Print.

Brenna, Dwayne. “George Dibdin Pitt: Actor and Playwright.” Theatre Notebook 52.1 (1998): 24-37. Print.

Booth, Michael. English Melodrama. London: Herbert Jenkins, 1965. Print.

Brooks, Peter. The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess. New haven: Yale UP, 1995. Print.

Cox, Phillip. Reading Adaptations: Novels and Verse narratives on the Stage, 1790-1840. Manchester, UK: Manchester UP, 2000. Print.

Curtin, Philip. The Image of Africa: British Ideas and Action, 1780-1850. Madison, WI: U of Wisconsin P, 1973. Print.

Davis, Paul. The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1990. Print.

Davis, Jim and Victor Emeljanow. Reflecting the Audience: London Theatregoing, 1840-1880. Hatfield: U of Hertfordshire P, 2001. Print.

Dickens, Charles. “The Amusements of the People.” Household Words 1.3 (13 April 1859): 57-60. Print.

—. “Two Views of a Cheap Theatre.” All the Year Round (25 February 1860): 416-421. Print.

The Era. 857. (25 February 1855): 10. Print.

Girot, Pascal. The Americas. Psychology Press, 1994. Print.

Grimsted, David. Melodrama Unveiled: American Theater and Culture, 1800‑1850. Berkeley: U of California P, 1987. Print.

Joseph, Gerhard. “Dickens, Psychoanalysis, and Film: A Roundtable.” Dickens on Screen. Ed. John Glavin. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

Kaplan, Cora. “Black Heroes/White Writers: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Literary Imagination.” History Workshop Journal Issue 46 (1998): 33-62. Print.

Mack, Robert. Introduction. Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Ed. Robert Mack. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007. Print.

—. The Wonderful and Surprising History of Sweeney Todd: The Life and Times of an Urban Legend. London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2007. Print.

Mayer, David. “Encountering Melodrama.” The Cambridge Companion to Victorian and Edwardian Theatre. Ed. Kerry Powell. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004. Print.

Meisel, Martin. Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1983. Print.

Moore, Haley. “George Dibdin Pitt.” Dictionary of Literary Biography. Detroit: Gale Cengage Learning, 2008: 293-299. Print.

Morley, Malcolm. “Dickens Contributions to Sweeney Todd.” The Dickensian 58.337 (Spring 1962): 92-95. Print.

Nicoll, Allardyce. A History of English Drama, 1660-1900, Volume 4. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1955. Print.

Pitt, George Dibdin. The String of Pearls, or the Fiend of Fleet Street. Dick’s Standard Plays 499. London: John Dick, 1883. Print.

The String of Pearls: A Romance. The People’s Periodical and Family Library. 1.7-24. Ed. Edward Lloyd. 21 November 1846-20 March 1847, in 18 numbers. Print.

Rahill, Frank. The World of Melodrama. State College, PA: Pennsylvania State UP, 1967. Print.

Smith, Helen. Sweeney Todd, Thomas Peckett Prest, James Malcolm Rymer and Elizabeth Caroline Grey. London: Jarndyce Books, 2002. Print.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Theory in the Margin: Coetzee’s Foe Reading Defoe’s Crusoe/Roxana.” English in Africa 17.2 (1990): 1-23. Print.

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Directed by Tim Burton. Starring Johnny Depp, Helena Bonham Carter, Alan Rickman, Sacha Baron Cohen, and Laura Michelle Kelly. Paramount Pictures. December 2007. (DVD April 2008.)

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. Book by Hugh Wheeler. Directed by Harold Prince. Starring Angela Lansbury and Len Cariou. Uris Theater, New York City. Opened 1 March 1979. 557 Performances.

Waters, Hazel. Racism on the Victorian Stage: Representation of Slavery and the Black Character. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007. Print.

Weltman, Sharon Aronofsky. “Boz Versus Bos in Sweeney Todd: Dickens, Sondheim, and Victorianness.” Dickens Studies Annual 42 (2011): 55-76. Print.

—. Editor, introduction, and detailed explanatory notes. Sweeney Todd: The String of Pearls, or The Fiend of Fleet Street by George Dibdin Pitt. Transcribed from British Library Manuscript and Playbill. Special issue of Nineteenth-Century Theatre and Film 38.1 (June 2011). Print.

Williams, Carolyn. Gilbert and Sullivan: Gender, Genre, Parody. New York: Columbia UP, 2010. Print.

Young, Robert. Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race. London and New York: Routledge, 1995. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] The closest “true story” of a Parisian barber-murderer in cahoots with a pastry chef neighbor was republished in 1824 as “A Terrific Story of the Rue de la Harpe, Paris” in The Tell Tale Fireside Companion and Amusing Instructor, a London magazine. The Newgate Calendar’s Scottish cannibal clan leader Sawney Beane, who lived in a cave and dined for decades off unwary travelers, is also cited as a model. Other possible antecedents include the myth of Procne and Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus. See Mack (Wonderful 159–65).

[2] “Amusements of the People” appeared in Household Words 1.3 (1850: 13 April, p.57). “Two Views” appeared in All the Year Round and was collected in The Uncommercial Traveller (417-418). See Weltman, “Bos Versus Boz in Sweeney Todd” for more on the relationship between Dickens, the novel The String of Pearls, and Sondheim’s musical Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street.

[3] See Robert Mack for a helpful chronology of many Sweeney Todd adaptations in his edition of the novel The String of Pearls (Oxford UP 2007): xxxi-xxxvi.

[4] Scholars will find the licensing manuscripts from 1743 to January 1824 in the Larpent Plays Collection at the Huntington Library. The Lord Chamberlain’s Plays collection ends in 1968 because a new Theatres Act was passed that ended theatrical censorship.

[5] This special issue of Nineteenth-Century Theatre and Film is my scholarly edition of Dibdin Pitt’s melodrama; the introduction discusses the material covered here (and much more about the play) in greater detail. All page numbers for quotations from Dibdin Pitt’s 1847 version refer to this edition.

[6] See Martin Meisel’s Realizations for the definitive book on this practice.

[7] See Weltman’s Sweeney Todd for a transcription of the playbill housed in the British Library (25-27).

[8] See Weltman’s “Introduction” for more examples of the interchangeability of Hector as dog and boy.

[9] See Spivak for discussion of Coetzee’s twentieth-century rewriting of Friday’s silence (13-18).

[10] For more on Dibdin Pitt’s plays concerning race, see Weltman Sweeney 16.

[11] Jackie Bratton and Hazel Waters point out the clear connection between sailors pressed into naval service and slaves kidnaped into slavery, giving extra poignancy to plays such as My Poll and My Partner Joe (1835) that portray the British navy patrolling the high seas to stop slave-trading ships and liberate their victims (Bratton 49, Waters 53).

[12] See Hazel Waters’s Racism on the Victorian Stage for more about the increasingly racist trajectory of how black characters are depicted on the Victorian stage (passim). For the intensification of racism as a defining cultural feature of the British imperial context from the 1880s onward, see Robert Young’s Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race (87); see also Philip Curtin’s The Image of Africa: British Ideas and Action, 1780-1850, where he explains the effect of “the new imperialism,” when Britain “entered fully into the scramble for Africa of the 1880’s and 1890’s” (Curtin xii).