Abstract

This essay considers the Royal Charter Storm, perhaps the most devastating weather event to occur in Britain in the nineteenth century, a gale that is named for the wreck of the Royal Charter steamship off the coast of North Wales and the subsequent drowning of most of its passengers and crew. Although this tragedy resulted in improvements in weather warning systems that contributed to the rise of modern forecasting, that is not the storm’s only legacy. In the aftermath of a parallel media storm, a host of reports ran in newspapers across the country in the days, weeks, and even months that followed, together producing a sense of this wide-ranging storm as a shared, national event. Among these reports was Charles Dickens’s account in All the Year Round, a striking portrayal of the losses associated with the wreck and an effort to ameliorate the suffering it had caused. Rather than predicting the weather, reports of the storm in the popular press turned to another kind of weather model of sorts, the retrospective work of memorializing and sympathy.

In the early hours of 26 October 1859, the Royal Charter steam clipper, en route from ![]() Melbourne to

Melbourne to ![]() Liverpool, found herself too close to the shore near

Liverpool, found herself too close to the shore near ![]() Moelfre on the coast of

Moelfre on the coast of ![]() Anglesey in

Anglesey in ![]() North Wales when winds began to pick up dangerously. Sending up distress signals, but finding no pilot to respond, the captain dropped the anchors, powered the coal engines, and eventually cut the masts, but to no avail. The ship was torn apart and then submerged by eight o’clock that same morning. Having originally sailed with a crew of 103 and 324 passengers, only 41 survived the wreck (Steele and Williams 3-5). Decades before the sinking of the Titanic, the fate of the Royal Charter was similarly unexpected. This 2719-ton, 200-horsepower marvel of Victorian shipping was fireproof, watertight, and iron-hulled.[1] Carrying a cargo of gold from the newly discovered Australian goldfields worth 500,000 pounds, she was on schedule to complete the journey in fewer than sixty days. Having successfully negotiated the tricky waters of

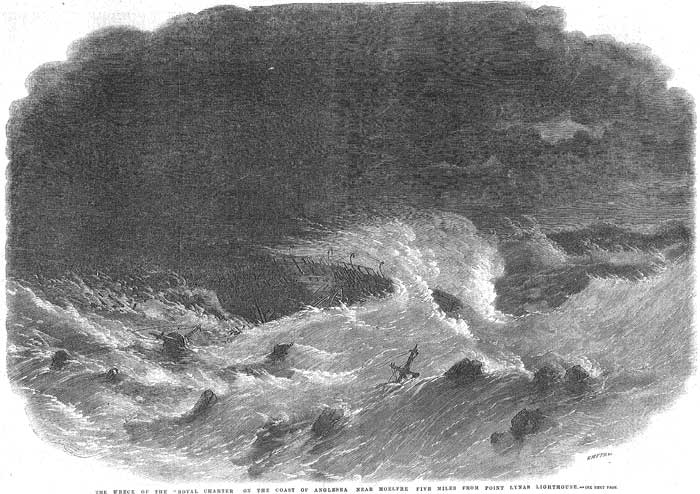

North Wales when winds began to pick up dangerously. Sending up distress signals, but finding no pilot to respond, the captain dropped the anchors, powered the coal engines, and eventually cut the masts, but to no avail. The ship was torn apart and then submerged by eight o’clock that same morning. Having originally sailed with a crew of 103 and 324 passengers, only 41 survived the wreck (Steele and Williams 3-5). Decades before the sinking of the Titanic, the fate of the Royal Charter was similarly unexpected. This 2719-ton, 200-horsepower marvel of Victorian shipping was fireproof, watertight, and iron-hulled.[1] Carrying a cargo of gold from the newly discovered Australian goldfields worth 500,000 pounds, she was on schedule to complete the journey in fewer than sixty days. Having successfully negotiated the tricky waters of ![]() the Cape of Good Hope, the journey home had seemed assured until, when only about seventy miles from Liverpool, the winds gathered devastating power to reach gale force 12. (See Fig. 1.)

the Cape of Good Hope, the journey home had seemed assured until, when only about seventy miles from Liverpool, the winds gathered devastating power to reach gale force 12. (See Fig. 1.)

The gale was by no means confined to the waters off North Wales, nor would the Royal Charter be the only loss, as this storm continued on for a further two or three days (Fitzroy, Weather Book 299-301). Beginning off the coast of ![]() Cornwall on 25 October, the storm grew the next day over the mainland, the North Sea, and then northeast into

Cornwall on 25 October, the storm grew the next day over the mainland, the North Sea, and then northeast into ![]() Scotland before reaching

Scotland before reaching ![]() Norway by the 27th (Anderson 110). Another storm brewed over 1-2 November, such that from 25 October until 9 November there were up to 343 wrecks and 748 lives lost as a result of the gales (“Autumnal Storms and Shipwrecks” 2). Among the fortunate ships to escape this fate was Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s the Great Eastern, surviving the storm by anchoring in

Norway by the 27th (Anderson 110). Another storm brewed over 1-2 November, such that from 25 October until 9 November there were up to 343 wrecks and 748 lives lost as a result of the gales (“Autumnal Storms and Shipwrecks” 2). Among the fortunate ships to escape this fate was Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s the Great Eastern, surviving the storm by anchoring in ![]() Holyhead Harbour “while,” as one seaman would later put it, “all round her the shores and harbour were strewn with wrecks” (Ballantyne 352). Named for what would become its most-cited victim, the Royal Charter Gale or the Royal Charter Storm (or, in Scotland, the Great Hyperborean Storm) has earned the reputation as one of the most devastating weather events in Britain in the nineteenth century (Lamb 135-36).

Holyhead Harbour “while,” as one seaman would later put it, “all round her the shores and harbour were strewn with wrecks” (Ballantyne 352). Named for what would become its most-cited victim, the Royal Charter Gale or the Royal Charter Storm (or, in Scotland, the Great Hyperborean Storm) has earned the reputation as one of the most devastating weather events in Britain in the nineteenth century (Lamb 135-36).

Losses were so serious and alarming that they prompted significant measures to improve storm warnings along Britain’s coasts, many at the recommendation of Robert Fitzroy.[2] Formerly captain of the HMS Beagle (see Ian Duncan, “On Charles Darwin and the Voyage of the Beagle”) and in 1853 appointed as advisor to the Board of Trade (forerunner of the Meteorological Office), Fitzroy was made head of a newly formed department of meteorological statistics. Fitzroy then conducted a detailed analysis of the tragedy and presented his findings to the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1860 (Anderson 48-49; 110 n.65). His recommendation for a storm-warning system was approved that same year; it was partly comprised of a set of visual signals that could be communicated from shore to ship, a mechanical contraption of cylinders and cones hoisted on pulleys (Gribbin and Gribbin 263-64).[3] But the new system also came to embrace the further possibilities of the existing telegraph network when thirteen storm glasses were eventually placed in telegraph offices around Britain’s coastal and fishing communities.[4] There, operators were charged with reading Fitzroy’s instruments and then sending the results swiftly to a central office in London, which then issued weather warnings based on the data it had received. The local telegraph operators would then hoist a signal.[5]

But these improvements in forecasting were not to be the gale’s only outcome. In addition to meteorological advancements was another effect of the Royal Charter Storm: the ways in which newspapers were reporting the weather to a non-specialist reading public. A day after the winds reached hurricane force, The Times printed a story simply entitled “The Gale,” which included reports on the wind-storm from across the nation received by telegraph from Liverpool, London, Plymouth, ![]() Portland, Portsmouth,

Portland, Portsmouth, ![]() Sussex,

Sussex, ![]() Dover, Brighton, Hartlepool, Bristol, and Exeter. These reports showed how the storm that had wrecked ships in coastal regions also wreaked havoc in London on the same day in October where, among other incidents, high winds were linked to downed trees, to several injuries “from being struck by tiles and chimneys,” and most spectacularly to “a woman being carried off her feet into [the

Dover, Brighton, Hartlepool, Bristol, and Exeter. These reports showed how the storm that had wrecked ships in coastal regions also wreaked havoc in London on the same day in October where, among other incidents, high winds were linked to downed trees, to several injuries “from being struck by tiles and chimneys,” and most spectacularly to “a woman being carried off her feet into [the ![]() Surrey] [C]anal” in

Surrey] [C]anal” in ![]() Peckham where she drowned (9). The links between events near Moelfre and in the metropole became clear. Similarly, when The Illustrated London News reported that “

Peckham where she drowned (9). The links between events near Moelfre and in the metropole became clear. Similarly, when The Illustrated London News reported that “![]() Chester and

Chester and ![]() Birkenhead Railway had been destroyed in two places; between

Birkenhead Railway had been destroyed in two places; between ![]() Conway and Holyhead an embankment had been washed away,” these storm-damage details mattered to readers elsewhere in Britain. Disruption to rail lines was not a local inconvenience but a matter of national concern in the by-now networked, imperial nation (“Wreck of the ‘Royal Charter,’ and Loss of About Four Hundred Lives” 413).

Conway and Holyhead an embankment had been washed away,” these storm-damage details mattered to readers elsewhere in Britain. Disruption to rail lines was not a local inconvenience but a matter of national concern in the by-now networked, imperial nation (“Wreck of the ‘Royal Charter,’ and Loss of About Four Hundred Lives” 413).

In the aftermath of the storm, however, reports of the gale itself—the power of the winds and the damage they caused—soon gave way to many column inches devoted to the particular loss of the Royal Charter ship. This wide-ranging wind storm, it seems, required a focal point in the papers, and the ship’s distress served as one for the growing and corresponding media storm: a means by which to transform for readers a robust weather occurrence into a narrative about human fear, heroism, and in the end, death for most. Print accounts of the disaster show how, following the event, weather became a matter for a shared outpouring of sympathy, extending from the provinces to the nation as a whole. “In this town and port alone,” stated one Liverpool paper, “from which the Royal Charter sailed, and where her officers and crews were shipped, hundreds of hearts are now throbbing in anguish over friends snatched from them at the moment when they were opening their arms to welcome them; and there is scarcely a town or country in England in which there will not be participators in their grief” (“Loss of the Royal Charter”).

As the testimonials of the few survivors began to circulate, the papers often represented the storm in the moments it was happening to those on board the ship; for these frightened passengers, the weather was not all around them but with them and in their very midst, as in one account in the Manchester Guardian: “Time passed anxiously and wearily; the storm still raged. Suddenly the vessel struck, not violently, not even with sufficient force to throw the passengers off their seats. Water then came pouring down into the cabin” (qtd. in “The Royal Charter”). As the weeks went on, the story of the ship continued to run, shifting from the Board of Trade inquiry (into the cause of the wreck of a merchant vessel) that was soon undertaken, to the matter of dealing with the bodies from the wreck that were washing ashore. One such list appearing in The Times on Friday, 2 December, by this time many weeks after the storm, mentions nearly two dozen still-unidentified bodies, and of these two whose only identifying marks were the initials monogrammed on their socks (“The Wreck of the Royal Charter” 7.) The Illustrated London News, in a moment of particular poignancy, recounts on 26 November 1859 that, when the body of one of the passengers, Captain Wither, washed ashore, he was still wearing his watch and that it “had stopped at half-past seven” (“The Wreck of the ‘Royal Charter’” 504). The ILN also printed a sentimental ballad on Christmas Eve, “Christmas on the Seashore,” and while the Royal Charter tragedy is not directly mentioned in this poem, this event seems implicit; the ballad makes mention of great winds and waves, a ship going down, and the drowning of passengers. It urges those who remain alive to take comfort since the victims of the sinking have now found eternal rest in Heaven: “Mourn not for those who bravely died” for “What we are seeking, they have found, — / Sweet rest, unbroken by the storm-winds fretting” (Heevey 41-42).

Apart from a reference to the real-life Royal Charter, the shipwreck in this poem would also have been recognizable to contemporary readers as a well-known evangelical trope: the shipwreck as an emblem of any crisis that might precipitate conversion and salvation, or as an emblem of moral courage amidst life’s trials and tribulations.[6] Storm and shipwreck had already figured in a similarly sentimental way in Charles Dickens’s earlier, 1850 fictional treatment in Chapter 55 of David Copperfield, “The Tempest,” in which Ham dies while trying to rescue the sailor who turns out to be Steerforth. In the middle of that chapter, David joins others on the ![]() Yarmouth beach who, in the midst of a violent wind-storm, look on in horror as a distressed schooner is pitched about:

Yarmouth beach who, in the midst of a violent wind-storm, look on in horror as a distressed schooner is pitched about:

The agony on the shore increased. Men groaned, and clasped their hands; women shrieked, and turned away their faces. Some ran wildly up and down along the beach, crying for help where no help could be. I found myself one of these, frantically imploring a knot of sailors whom I knew, not to let those . . . lost creatures perish before our eyes. (648)

In what ensues, Ham resolves to make a rescue attempt with the aid of a rope secured by some men on the shore at whatever the cost to his own life, and just as the ship has begun to part in the middle with Steerforth clinging to the one remaining mast.[7]

When Dickens, a decade later, wrote a journalistic account of a real-life wreck, that of the Royal Charter, his coverage of local salvage-work assesses both the effects and the affects of the storm. It was published in All the Year Round on 28 January 1860 as “The Shipwreck” and reprinted the following year along with other essays in The Uncommercial Traveller.[8] “The Shipwreck” is a sombre first-person account of the storm’s local aftermath in the Welsh community close to where the ship went down, one that also includes, in Dickensian-fashion, an instance of the political uses to which sentiment is often put.[9] Upon seeing the wreck, Dickens relates how he is taken aback by the extent of the damage to the ship. But as an “uncommercial” traveler, he is struck particularly by the gold that remains, a visible reminder and remainder of the ship’s link to a commercial, imperial economy: “So tremendous had the force of the sea been when it broke the ship, that it had beaten one great ingot of gold, deep into a strong and heavy piece of her solid iron-work: in which, also, several loose sovereigns that the ingot had swept in before it, had been found, as firmly embedded as though the iron had been liquid when they were forced there” (Dickens 4).[10] By 12 January 1860, an American paper, The Country Gentleman, was reporting that the value of the recovered gold from the wreck had reached £275,000.

Dickens’s focus, though, turns soon from the wreck and the gold that was fueling the salvage, to the trauma visited upon the community near where the ship had struck, as the bodies, and not just sovereigns, wash up. For Dickens, the incalculable cost is human, and these costs include not just the dead but also the living, including the local clergyman, the Reverend Stephen Roose Hughes of ![]() Llanallgo parish, to whom fall the duties of dealing with the dead and with those who grieve for them. Hughes comes across as an exemplary character in Dickens’s account, a man of tireless work and boundless empathy in the midst of great mourning: “So cheerful of spirit and guiltless of affectation, as true practical Christianity ever is!” (4). Dickens follows Hughes to the church, which has been transformed into a makeshift morgue. Here, the clergyman spends countless hours devoted to the difficult task of trying to identify the dead. Meanwhile, in the churchyard, there are already 145 victims of the wreck buried, for whom Hughes has conducted all the funeral services.

Llanallgo parish, to whom fall the duties of dealing with the dead and with those who grieve for them. Hughes comes across as an exemplary character in Dickens’s account, a man of tireless work and boundless empathy in the midst of great mourning: “So cheerful of spirit and guiltless of affectation, as true practical Christianity ever is!” (4). Dickens follows Hughes to the church, which has been transformed into a makeshift morgue. Here, the clergyman spends countless hours devoted to the difficult task of trying to identify the dead. Meanwhile, in the churchyard, there are already 145 victims of the wreck buried, for whom Hughes has conducted all the funeral services.

But the most daunting task, one which Hughes continues to perform, is to write condolence letters, of which Hughes has composed an astonishing 1,075. This makes Dickens anxious to see the letters, ten of which he reprints for his All the Year Round audience to read for themselves: letters written by family and friends of the victims to thank Hughes, to make one inquiry or another in the course of identification, and one especially touching note from a grieving husband which begs the clergyman to write to him simply for consolation, “to prevent my mind from going astray” (8). Having reached a high emotional pitch with these letters—which Dickens includes one by one without linking commentary, such that they stand on their own generated and accumulated affect—he concludes the essay with “A Blessing,” one that is, in part, a wish for good weather: “May the sun of glory shine around thy bed . . . . May no sorrow distress thy days; may no grief disturb thy nights” (10). The blessing is for his readers, who have made a harrowing journey to the scene of the Royal Charter with him, and also a means to express a sense of admiration for Hughes, who weathers the storm’s aftermath with great fortitude.

For Dickens, then, writing about this tragic outcome of weather comes to rest upon a portrait of human sympathy in the person of Reverend Hughes, whom Brigid Lowe calls “Dickens’s emblem for the preservation of memory in the face of time” (30). Hughes apparently carried out his work of remembering far beyond the call of duty, for by 1862 he was dead at the age of 47. His tombstone notes his work in connection to the Charter Storm and observes that “[t]he subsequent effects of those exertions proved too much for his constitution, and suddenly brought him to an early Grave” (qtd. in Steele and Williams 25). Among memorials to the actual wreck and its victims was a monument erected in the Llanallgo churchyard “by public subscriptions to the memory of those who perished in the wreck of the Royal Charter” (“Remains of the Royal Charter” F5).

Dickens’s sympathetic and memorializing weather report might stand in contrast to a more dispassionate and standardized weather model that would follow, and which might be best summed up as the newspaper weather map. Robert Fitzroy had already begun mapping the weather in 1857 (Anderson 191), but the first map to appear in the newspapers for the British public was published in The Times on 1 April 1875 (“Weather Chart”).[11] Composed not by Fitzroy but by the polymath Francis Galton, it showed barometric pressure, temperature, and winds superimposed upon a map of the British Isles and parts of Western Europe (Hill). As Jen Hill has shown, the weather map did the cultural work of shaping British notions of geography and nationhood. It resembles, in other words, the weather map of today that inducts us into a sense of what the weather will be like: the fore-runner to our benign but informative five-day forecast. This kind of weather model is, in a sense, observed by John Ruskin (although in his case, not dispassionately) by 1884, when he delivers his lecture, “The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century,” to the ![]() London Institution. Ruskin’s storm is, of course, the result of industrial manufacturing and not the forces of nature. But more to the point here, his clouds portend a future moment, which Ruskin calls his listeners to predict and to read. He urges at the end of his lecture, sounding like prophet as much as weatherman: “What is best to be done, do you ask me? The answer is plain. Whether you can affect the signs of the sky or not, you can the signs of the times” (8).

London Institution. Ruskin’s storm is, of course, the result of industrial manufacturing and not the forces of nature. But more to the point here, his clouds portend a future moment, which Ruskin calls his listeners to predict and to read. He urges at the end of his lecture, sounding like prophet as much as weatherman: “What is best to be done, do you ask me? The answer is plain. Whether you can affect the signs of the sky or not, you can the signs of the times” (8).

The first newspaper weather map to be published, however, as Hill points out, did not prophesy or predict the weather. Rather, it reported on the previous day’s weather of 31 March. This quirk of the first weather map—that it was retrospective rather than anticipatory—might lead us to consider whether the Royal Charter Storm of 1859 is part of a cultural moment when reading the weather was similarly not yet fully predictive. While weather-warning systems would improve after the Great Charter Storm, the storm did not function for the reading public as a sign of the times, as portent, but in the form of newspaper reports concerning the scale and scope of what had happened, as the popular press turned finally to meditations on grave markers and stone memorials to the wreck’s victims.

Whenever today’s cable news storm-trackers try to anticipate the next hurricane to make landfall, or where the impending tornado will hit, their eagerness to predict is all too apparent; there is a sense that to report the weather is to close the gap between when weather will happen and as it happens. Television reporters stand at the ready dressed in the latest rain- and wind-proof gear, eager to call the storm into being while their images are beamed simultaneously by satellites. Victorian accounts of the Royal Charter Storm remind us of how difficult it is to pin down our sense of the weather as a single, meaningful event—and why, in the face of that uncertainty, newspapers and journalists in 1859 might have turned as they did to mapping the extent of a shared national sympathy as an ensuing weather model.[12]

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published February 2013

Lysack, Krista. “The Royal Charter Storm, 25-26 October 1859.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Allingham, Philip V. “David Copperfield and Contemporary Shipwrecks.” The Victorian Web: Literature, History, and Culture in the Age of Victoria. N.p., 23 September 2010. Web. 9 May 2012.

Anderson, Katharine. Predicting the Weather: Victorians and the Science of Meteorology. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2005. Print.

“The Autumnal Storms and Shipwrecks.” The Shipwrecked Mariner: A Quarterly Maritime Magazine 7.25 (1860): 1-16. Google Books. Web. 9 May 2012.

Ballantyne, Robert Michael. Man on the Ocean. London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1863. Google Books. Web. 9 May 2012.

Dickens, Charles. David Copperfield. (1850) Ed. Mariel Fyee. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1973. Print.

—. “The Shipwreck.” The Uncommercial Traveller. 1861. London: Chapman and Hall, 1866. Print.

Fitzroy, Robert. The Weather Book: A Manual of Practical Meteorology. 2nd ed. London: Longman, 1863. Print.

“The Gale.” The Times 27 October 1859: B9. Gale Group. Web. 9 May 2012.

Gribbin, John and Mary Gribbin, FitzRoy: The Remarkable Story of Darwin’s Captain and the Invention of the Weather Forecast. New Haven: Yale UP, 2004. Print.

Heevey, Eleanora L. “Christmas on the Seashore.” The Illustrated London News 24 December (1859): C609. Print.

Hill, Jen. “Weather as (Inter)National Performance: The Weather Map, Francis Galton, and the Isobar.” North American Victorian Studies Conference. Vanderbilt University, Nashville. 5 November 2011. Conference Presentation.

Hilton, Boyd. The Age of Atonement: The Influence of Evangelicalism on Social and Economic Thought, 1795-1865. Oxford: Clarendon, 1988. Print.

Lamb, H. H. [Hubert Horace]. Historic Storms of the North Sea, British Isles and Northwest Europe. Contributor Knud Frydendahl. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1991. Print.

“Loss of the Royal Charter.” Liverpool Mercury 28 October 1859: n.pag. Print.

Lowe, Brigid. Victorian Fiction and the Insights of Sympathy. London: Anthem, 2007. Print.

Marriott, William. “The Earliest Telegraphic Daily Meteorological Reports and Weather Maps.” Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 28 (1902): 123-31. Print.

McKee, Alexander. The Golden Wreck: The True Story of a Great Maritime Disaster. London: Souvenir Press, 1961. Print.

Middleton, W[illiam] E[dgar] Knowles. Meteorological Instruments. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1941. Print.

“Remains of the Royal Charter.” The Times 6 July 1863: F5. Gale Group. Web. 9 May 2012.

“Review of Passing Events.” The Country Gentleman 15.2 (12 January 1860): 36-37. Google Books. Web. 25 January 2013.

“The Royal Charter.” Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser 1 November 1859: n.pag. Print.

“Royal National Life-boat Institution.” The Illustrated London News 5 November 1859: B444. Print.

Ruskin, John. The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century: Two Lectures Delivered at the London Institution, February 4th and 11th, 1884. Sunnyside, Kent. G. Allen, 1884. Print.

Scoresby, William. Journal of a Voyage to Australia, and Round the World for Magnetical Research. 1859. Ed. Archibald Smith. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2011. Google Books. Web. 9 May 2012.

Steele, Philip and Robert Williams. Shipwrecked! Charles Dickens and The Royal Charter Storm. 2nd rev. ed. Llansadwrn: Llyfrau Magma, 2009. Print.

“Weather Chart, March 31, 1875.” The Times 1 April 1875. Gale Group. Web. 17 May 2012.

“The Wreck of the Royal Charter.” The Illustrated London News 5 November 1859: A-C448. Print.

“The Wreck of the ‘Royal Charter.’” The Illustrated London News 26 November 1859: C504. Print.

“The Wreck of the Royal Charter.” The Times 2 December 1859: F7. Gale Group. Web. 9 May 2012.

“Wreck of the ‘Royal Charter,’ and Loss of About Four Hundred Lives.” The Illustrated London News 29 October 1859: C413. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] The Illustrated London News provides the weight and horse-power of the Royal Charter (“The Wreck of the Royal Charter” 448). For more on the Royal Charter’s dimensions and capabilities, see, for instance, Scoresby 14-19 and McKee.

[2] While there were great losses, there were also some rescues. The Illustrated London News, for example, reported on 5 November 1859 that the Royal National Life-boat Institution held a meeting, during which it handed out rewards totaling 42 pounds, 10 shillings to crews “for saving large number of lives during the recent terrific storms on the coasts” (444). To Joseph Rodgers, a Maltese crewman, was awarded the gold medal (and 5 pounds) for his rescue of persons from the Royal Charter before it went down.

[3] See also Fitzroy’s description of this storm warning system in his The Weather Book 1-46.

[4] For more on such instruments and others, see, for instance, Middleton’s Meteorological Instruments.

[5] Fitzroy embraced yet another technology of weather forecasting: the weather map. For more on Fitzroy’s synoptic maps, see, for instance, Anderson 190-95.

[6] On the significance of shipwrecks to evangelical discourse, see, for instance, Boyd Hilton’s The Age of Atonement.

[7] Philip V. Allingham has explored how the wrecks of three other ships in 1850—those of the Vine (off Whitby), the Onyx (at Ostend), and the Royal Adelaide (off ![]() Margate)—occur within months of Dickens’s October 1850 installment of David Copperfield, in which his fictional storm appears and offers a convincing account of the ways in which Dickens’s fictional story resembles these three storms in particular.

Margate)—occur within months of Dickens’s October 1850 installment of David Copperfield, in which his fictional storm appears and offers a convincing account of the ways in which Dickens’s fictional story resembles these three storms in particular.

[8] As Steele and Williams note (3), Dickens had earlier written about a fictional storm and shipwreck in his 1850 David Copperfield. For mentions of still more treatments of shipwreck in Dickens, see, for instance, Anderson 110 n. 67.

[9] On the political uses of sentiment, see, for instance, Brigid Lowe’s Victorian Fiction and the Insights of Sympathy.

[10] Nearly four years on, The Times was still reporting on continued operations to recover the gold from the sunken wreck, some of these by treasure-seekers (“Remains of the Royal Charter” 5).

[11] See also William Marriott, “The Earliest Telegraphic Daily Meteorological Reports and Weather Maps,” 123-31.

[12] Thanks to my research assistant, Miriam Love, for her work in locating newspaper articles for this essay, and thanks also to the anonymous readers.