Abstract

This essay examines depictions of one of the infamously well-known region of London called “The East End.” Scholarly and popular discussions of this part of the city have been dominated by texts emphasizing the East End’s seedy or sensational social and economic features. In particular, popular writing has focused on the history of poverty, crime, and resident “alien” or immigrant groups living in the East End. While such stereotypes were often loud in their sensationalism, and while they often overpowered competing narratives, this essay makes the case for reading them alongside a range of narratives about the East End, many of which were produced by residents of this part of London. In what follows, I consider a mix of insider and outsider lenses, of well-known and lesser-known voices that produced a varied range of depictions of the nineteenth-century East End. In the process, I argue that the East End ought not to be characterized as simply a site of crime and poverty. To understand this important part of London, we must instead examine a fuller range of voices emerging from disparate, often competing, perspectives. Through this mix, we can begin to register the East End’s economic, cultural and social diversity witnessed and described in discordant ways by visitors and residents alike.

![]() On the morning of 8 September 1888, the periodical The Illustrated London News reported the first of many articles about the gruesome Whitechapel murderer, otherwise known as Jack the Ripper. The reporter explained,

On the morning of 8 September 1888, the periodical The Illustrated London News reported the first of many articles about the gruesome Whitechapel murderer, otherwise known as Jack the Ripper. The reporter explained,

At a quarter to four on Friday morning Police-constable Neil was on his beat in

Buck’s-row, Thomas-street, Whitechapel, when his attention was attracted to the body of a woman lying on the pavement close to the door of the stable-yard in connection with

Essex Wharf. Buck’s-row, like many other miser thoroughfares in this and similar neighbourhoods, is not overburdened with gas lamps, and in the dim light the constable at first thought that the woman had fallen down in a drunken stupor and was sleeping off the effects of a night’s debauch. With the aid of the light from his bullseye lantern Neil at once perceived that the woman had been the victim of some horrible outrage. (Ryder n.p.)

This passage includes details that came to define both newspaper coverage of the murders and descriptions of the locations where they occurred—in ![]() the East End of London. The writer begins with a lurid description of Whitechapel, which by 1888 was known to be one of the poorest districts in London. The article makes particular mention of the dark street, the homeless woman (homeless, that is, for the evening), and the body’s location near the Wharf. The docks were built from the 1790s-1830s and brought shipping industry to the East End while simultaneously underscoring its identity as a place populated by foreign sailors and where newly arrived immigrants had long made a home for themselves. Over the course of the nineteenth century, literary and print culture constructed the East End accordingly, as both a place of foreigners and a foreign place. Such accounts focused on depictions of the East End’s extreme poverty, menacing aliens, and dark windy streets, which effectively prepared readers for the stories that circulated during the Ripper investigation later in the century. The description in the Illustrated London News of a policeman holding up a bull’s-eye lantern is therefore not an insignificant detail, for the light that shines on the outraged victim appears to illuminate the darkness and, like much of the writing about the East End in this period, offers a presumably unbiased, objective account of East London’s horrors.

the East End of London. The writer begins with a lurid description of Whitechapel, which by 1888 was known to be one of the poorest districts in London. The article makes particular mention of the dark street, the homeless woman (homeless, that is, for the evening), and the body’s location near the Wharf. The docks were built from the 1790s-1830s and brought shipping industry to the East End while simultaneously underscoring its identity as a place populated by foreign sailors and where newly arrived immigrants had long made a home for themselves. Over the course of the nineteenth century, literary and print culture constructed the East End accordingly, as both a place of foreigners and a foreign place. Such accounts focused on depictions of the East End’s extreme poverty, menacing aliens, and dark windy streets, which effectively prepared readers for the stories that circulated during the Ripper investigation later in the century. The description in the Illustrated London News of a policeman holding up a bull’s-eye lantern is therefore not an insignificant detail, for the light that shines on the outraged victim appears to illuminate the darkness and, like much of the writing about the East End in this period, offers a presumably unbiased, objective account of East London’s horrors.

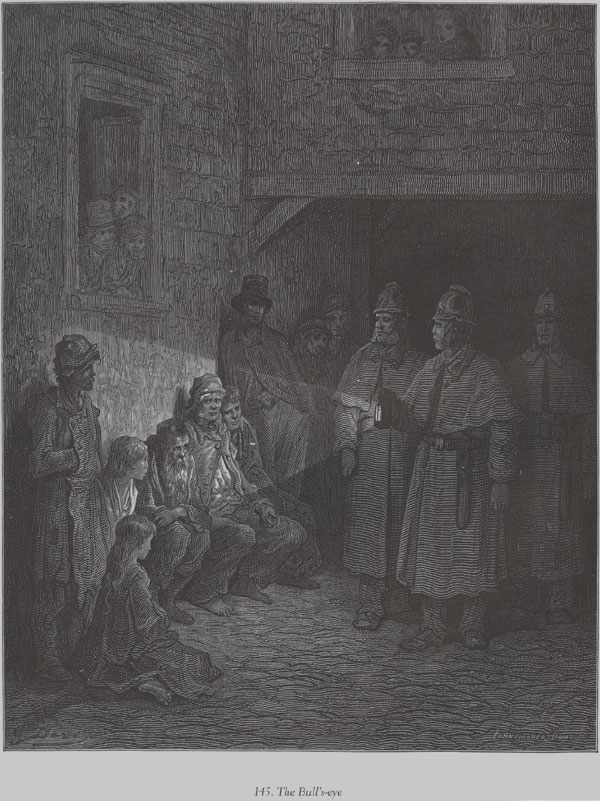

Police-Constable Neil was not alone in using a bull’s-eye lantern to present a visible and authentic portrait of the East End. A few years earlier, Gustave Doré offered a similar account in his illustration of Whitechapel titled, “The Bull’s-eye” (Fig 1) in his graphic series, London, A Pilgrimage (1872). In Doré’s illustration, a policeman shines his lamp into the dusky gloom, highlighting the depravity of sheepish, ill-clothed homeless people ambushed by the lantern’s harsh light. Indeed, depictions of a degraded East End were ubiquitous throughout the nineteenth century. The following essay traces the contours of the popular construction of the nineteenth-century East End, much of which has been dominated by sensational narratives focusing on poverty, crime, and darkness of every imaginable kind. Like the bull’s-eye lantern, these texts typically position the narrative lens outside of the East End looking in, with a tone of eagerness to witness how the other half of London lived.[1] Deborah Epstein Nord explains that this kind of viewing lens was a common feature of nineteenth-century writing about the city. Frequently, the onlooker took the shape of “the rambler, the stroller, the spectator, the flaneur—[who] is a man. [. . .] He begins as a visible character in the urban sketch, a signature . . . who is both authorial persona and fictional actor on the city streets, and ends as the invisible but all-seeing novelist, effacing all of himself but his voice in the evocation of an urban panorama” (1). According to Judith R. Walkowitz and Peter Keating, constructions of the nineteenth-century East End also made frequent allusions to British global power. Walkowitz notes, “[t]he opposition of East and West increasingly took on imperial and racial dimensions, as the two parts of London imaginatively doubled for England and its Empire” (26). L. Perry Curtis, Jr. adds that the regions of East and West were not just geographical markers, but served ideological ends. As he puts it, popular writers from this period “binarized their urban world into zones of light and darkness, cleanliness and dirt, safety and danger, virtue and vice. In their febrile imaginations all the drainpipes and sewers of the metropolis seemed to empty into the East End” (37).

Narratives about the East End created by visitors—flaneurs, journalists, social reformers, or travelers—present important perspectives on the way Victorian culture wrestled with the rise of the modern city at a moment when crime, poverty, and access to education became subjects of national debate. As the century wore on, Gareth Stedman Jones notes, “Victorian civilization felt itself increasingly threatened by ‘Outcast London’” or by those who lived within the urban sphere but represented a foreign or outsider class because of their economic and/or social position (Stedman Jones 1). The expression “Outcast London” used in many of the print materials produced after the 1850s “symbolized the problem of the existence and persistence of certain endemic forms of poverty, associated together under the generic term, casual labour” or those without permanent work (Stedman Jones 1). In some cases, travelers or flaneurs recording their observations or interactions with East End residents were attempting to effect economic or spiritual improvements on the lives of the poor. Other writers instead sought to expose the gritty filth and greasy abundance of people overpopulating narrow city streets. Seth Koven explains that “For the better part of the century preceding World War II, Britons went slumming to see for themselves how the poor lived. They insisted that firsthand experience among the metropolitan poor was essential for all who claimed to speak authoritatively about social problems” (Koven 1).

Yet, in speaking “authoritatively” these viewers traversed the city streets as voyeurs, gazing, questioning, and analyzing only to return to their homes, located in other parts of London, to record their accounts of urban street life. Their authority was secured by their viewing distance, their objectivity, even in their direct encounters with the people they met on the streets. Admittedly, it may seem tempting to privilege these seemingly objective views, especially given that by the 1880s a significant portion of the East End’s population was starving, a serial murderer was on the loose, and religious or racial persecution in other nations had the effect of prompting non-Christian and non-English immigration to the East End.

In what follows, I argue that, in order to begin to understand this important and complex region of London, we must instead examine a fuller range of voices emerging from a variety of perspectives. I proceed not by focusing on the outsiders looking in—the group Nils Roemer describes as those who held “a privileged viewing position” (419).[3] I turn, rather, to a mix of insider and outsider lenses, of well-known and lesser-known voices, to open up a place in which to consider both the range and interplay of depictions of East London. As we shall see, it is only by viewing such divergent texts that we can begin to register the East End’s complex economic, cultural, and social diversity at this transformative moment in its history.

The Formation of the East End

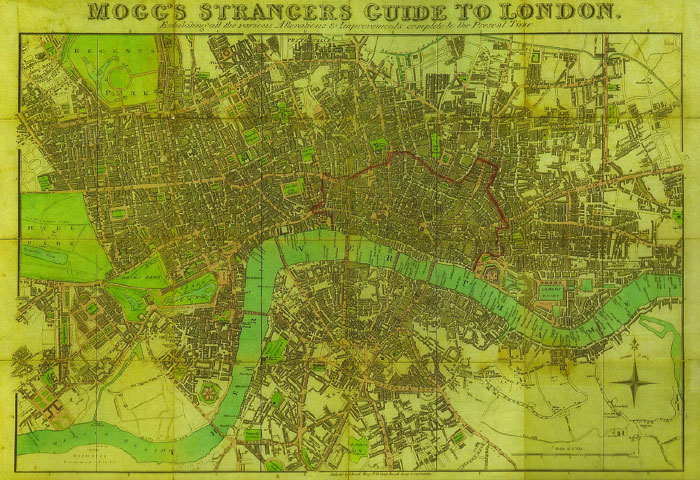

While narrative and visual cultures shaped the way the East End came to be known in the nineteenth-century and beyond, equally powerful is the fact of geography, for the East End is situated not only outside of the original boundaries of Roman Londinium, but down river, where the trash, smells, and, as Charles Dickens observed in Our Mutual Friend (1864-5), dead bodies flowed away from central London and through the East End before heading out to sea. In the suggestively named map, Moggs’s Stranger’s Guide to London (1834; Fig 2), a red line designates the old boundaries of Londinium, the Roman settlement created in 50 AD. The area to the east of the Norman-built ![]() Tower of London, according to some accounts, marks the boundary of the East End, while the space to the immediate north and west of the Tower of London designate the area known as the “City” (Palmer xi). The red line ascribes London’s boundaries, marking the start of the territory known as east London in the area to the east of the tower. Yet, no delineating line marks the far boundary of the East End. Perhaps understandably, then, where the East End ends geographically has been a subject of confusion or contention. Alan Palmer maintains that the “traditional limits” of the nineteenth-century East End included “the old Inner London Boroughs of

Tower of London, according to some accounts, marks the boundary of the East End, while the space to the immediate north and west of the Tower of London designate the area known as the “City” (Palmer xi). The red line ascribes London’s boundaries, marking the start of the territory known as east London in the area to the east of the tower. Yet, no delineating line marks the far boundary of the East End. Perhaps understandably, then, where the East End ends geographically has been a subject of confusion or contention. Alan Palmer maintains that the “traditional limits” of the nineteenth-century East End included “the old Inner London Boroughs of ![]() Hackney and

Hackney and ![]() Tower Hamlets, together with the western fringe areas of

Tower Hamlets, together with the western fringe areas of ![]() Hoxton and Shoreditch and the dockland overflow into

Hoxton and Shoreditch and the dockland overflow into ![]() West Ham and East Ham” (Palmer xvii). The Tower Hamlets, located on the eastern side of the Tower of London, were comprised of a number of “hamlets” or boroughs that included places such as

West Ham and East Ham” (Palmer xvii). The Tower Hamlets, located on the eastern side of the Tower of London, were comprised of a number of “hamlets” or boroughs that included places such as ![]() Bethnal Green,

Bethnal Green, ![]() Spitalfields,

Spitalfields, ![]() Stepney, Whitechapel, Wapping,

Stepney, Whitechapel, Wapping, ![]() Mile End, and beyond. To complicate matters, the geographical boundaries of the area termed “the East End” continually shifted over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As the city grew modern in this period, as increasing numbers of people migrated east of the City, and as transportation expanded, boundaries and spatial identities changed in response. Paul Newland explains that some of the confusion about defining this area “demonstrate[s] how far it remains a profoundly amorphous, ambiguous space—a space that has never been clearly or adequately defined, delineated or drawn. It is not, and has never been, a village, town or borough. But if it is not a mapable material space, it certainly functions as an enigmatic imaginative space” (17). Throughout the nineteenth century, writers commonly turned to the East End as a powerful emblem of modern urban life, and as a space capable of arousing fear, fascination, and repudiation in readers. Hence, despite the difficulty of pinning down East End boundaries, this space remained a powerful imaginative centerpiece in literature of London.

Mile End, and beyond. To complicate matters, the geographical boundaries of the area termed “the East End” continually shifted over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As the city grew modern in this period, as increasing numbers of people migrated east of the City, and as transportation expanded, boundaries and spatial identities changed in response. Paul Newland explains that some of the confusion about defining this area “demonstrate[s] how far it remains a profoundly amorphous, ambiguous space—a space that has never been clearly or adequately defined, delineated or drawn. It is not, and has never been, a village, town or borough. But if it is not a mapable material space, it certainly functions as an enigmatic imaginative space” (17). Throughout the nineteenth century, writers commonly turned to the East End as a powerful emblem of modern urban life, and as a space capable of arousing fear, fascination, and repudiation in readers. Hence, despite the difficulty of pinning down East End boundaries, this space remained a powerful imaginative centerpiece in literature of London.

The East End’s identity was rendered amorphous by other factors as well, including its name. Is it really an end, we might wonder? Might this space be read more productively as a beginning, or as the space that opens on the other side of the Tower of London? Printed records indicate that as early as 1756 a space known as “the East End” had already been identified as separable from the rest of London. One notable example of this view is a work titled, A New and Accurate Description of the Present Great Roads and the Principle Cross Roads of England and Wales, Commencing at London, which titled one of its chapters “The Eastern Roads or Those Going from the East End of London”(129). Just a few years later, in 1782, The London Guide, Describing the Public and Private buildings of London, Westminster, & Southward included a reference to the white tower in the Tower of London: “this erection stands on the north of the ![]() Thames, at the east end of London” (25). In this case, the first letters—“east” and “end”—each appear with a lower case “e.” In fact, prior to the 1860s the place name “East End” appeared variously with capital and lower-case letters. Dickens would refer to Whitechapel in his 1837 novel Oliver Twist as “the eastern suburbs,” suggesting that, even if the East End’s exact location was understood to have a distinct character early in the nineteenth century, its formal name or status as a proper noun remained in flux (171). In 1797, Johann Wilhelm von Archenholz, a Prussian writer and historian, offered a description of the East End that anticipates later formulations of this space. In his work, A Picture of England: Containing a description of the laws, customs, and manners of England, von Archenholz explains “There has been, within the space of twenty years, truly a migration from the east end of London to the west” (119). Already by this point, as the following passage suggests, this traveler emphasizes the East End’s undesirable features. Von Archenholz continues,

Thames, at the east end of London” (25). In this case, the first letters—“east” and “end”—each appear with a lower case “e.” In fact, prior to the 1860s the place name “East End” appeared variously with capital and lower-case letters. Dickens would refer to Whitechapel in his 1837 novel Oliver Twist as “the eastern suburbs,” suggesting that, even if the East End’s exact location was understood to have a distinct character early in the nineteenth century, its formal name or status as a proper noun remained in flux (171). In 1797, Johann Wilhelm von Archenholz, a Prussian writer and historian, offered a description of the East End that anticipates later formulations of this space. In his work, A Picture of England: Containing a description of the laws, customs, and manners of England, von Archenholz explains “There has been, within the space of twenty years, truly a migration from the east end of London to the west” (119). Already by this point, as the following passage suggests, this traveler emphasizes the East End’s undesirable features. Von Archenholz continues,

The east end, especially along the shores of the Thames, consists of old houses, the streets there are narrow, dark, and ill paved; inhabited by sailors and other workman who are employed in the construction of ships, and by a great part of the Jews. The contrast between this and the west is astonishing; the houses here are mostly new and elegant; the squares are superb, the streets straight and open, nor is any city in Europe so well paved (119).

A few years later, the novelist Pierce Egan would recount a slightly different characterization of the East End in his novel Life in London (1821), illustrated by Isaac and George Cruikshank. The novel tells the story of three friends who have raucous adventures throughout the city of London, including sites east of the Tower. It is in the “East End” where they drink wine, become lose tongued, and make comparisons between the high-class gentleman’s club, “![]() Almacks at the

Almacks at the ![]() West End” and the eastern social space of “All-Max in the East” (226; Fig. 4). In the image by the Cruikshank brothers, the rowdy adventures arrive at a pub where they are attended by the locals, who flirt, dance, and deliver food for their guests. Egan’s East End appears to be a long way from the murderous sordidness of the Whitechapel murderer. Still, however, we witness elements of crowdedness and tourism that would come to define later images. According to Egan’s narrative and Cruikshank’s corresponding text, by 1821 the East End had become a place to visit for entertainment, drinking, and consummate partying.

West End” and the eastern social space of “All-Max in the East” (226; Fig. 4). In the image by the Cruikshank brothers, the rowdy adventures arrive at a pub where they are attended by the locals, who flirt, dance, and deliver food for their guests. Egan’s East End appears to be a long way from the murderous sordidness of the Whitechapel murderer. Still, however, we witness elements of crowdedness and tourism that would come to define later images. According to Egan’s narrative and Cruikshank’s corresponding text, by 1821 the East End had become a place to visit for entertainment, drinking, and consummate partying.

While Egan’s narrative keeps its focus on the men who travel around London, it includes characters representing London’s immigrant groups. The book’s illustrators, the Cruikshank brothers, depict, for example, African-Caribbean figures dancing with the adventurers. The image’s title, “Lowest Life in London” works to constitute and associate the identities of those represented in the image with the space in which they appear in the narrative—the East End. Moreover, the caption, “Tom, Jerry, and Logic among the unsophisticated Sons and Daughters of Nature at All Max in the East” constructs East End foreignness against a presumably refined world of the West End.[4] Almacks in the west was a prominent and exclusive social and dance club. The slippage from real place, Almacks in the west, to the imaginary site construed as its uncultivated opposite, All-Max in the East, underscores the relational qualities of London geography. Thus, on one level the illustration mocks the East End as a destination for fleeting West End adventures. Yet, the image also recalls the role of visual art, in this case-book illustration, in imagining the East End’s racial, cultural, and religious diversity through a critical lens.

John Marriott recalls that “Black seamen had landed in East London ever since it emerged as a major maritime centre [in the 1790s]. Along with Asian lascars, they were vital to the crews of British shipping but since they possessed few rights, and shop owners felt under no obligation to provide for them once they reached London, many were simply abandoned and had to fend for themselves until a return passage could be found” (331). In some ways, then, the depiction in this text of the East End as a space of foreigners was not completely unfounded. Indeed, many immigrants from around the globe found a home in London’s East End. What is troubling about Egan’s and Cruikshanks’ depictions is not their image of the East End’s cultural diversity, but the framing of this space as low, wild, and uncivilized. Such associations emerge in the narrative and visual rhetoric of the text through the perspective of the well-educated West Enders who go “slumming” for fun, observing along the way the rowdy crowds that engage them in their adventures. Efraim Sicher explains that such texts—both Egan’s writing and the Cruikshanks’s illustration—were classic examples of a new way of imagining the city sphere. As he puts it, this was a period “when radical shifts took place in perceptions of the city in literary, artistic, and popular representations of London. These shifts were accompanied by new technologies of representation, such as the magic lantern, the diorama, and photography, which radically altered both the optical image and the visibility of the observer” (Sicher 39). Just like the bull-lantern’s exposure depicting how the other half lives in darkness, the Cruikshank brothers’ image offers a seemingly objective depiction of “lowest-life” dancers. According to Sicher, “London was, in Egan’s words, a ‘complete cyclopaedia,’ captured by a camera obscura that represented the nation’s wealth and health, without the viewer being seen” (Sicher 40). One wonders how this image might have been drawn or narrated by those depicted as the boisterous dancers. Like so many popular texts from this period, the narrative emerges from the perspective of the visitors, foreclosing any possibility of insider perspectives, or voices from the players and residents who entertain the West End pleasure seekers.

Following the publication of Life in London, George Cruikshank would move on to illustrate Charles Dickens’s novel Oliver Twist (1837). One of the most threatening characters in the novel, Fagin, is imagined as a social deviant, a Jew, and a resident of Whitechapel, who hoards money and preys upon orphan children. And while the eponymous hero is understood to be an outsider in the East End, as the following passage makes clear, Fagin appears to be an inveterate insider, a product of East End primordial mud and slime:

[In] The neighbourhood of Whitechapel [. . .] the Jew stopped for an instant at the corner of the street, and, glancing suspiciously round, crossed the road, and struck off in the direction of Spitalfields. [. . .] The mud lay thick upon the stones: and a black mist hung over the streets; the rain fell sluggishly down: and everything felt cold and clammy to the touch. It seemed just the night when it befitted such a being as the Jew, to be abroad. As he glided stealthily along, creeping beneath the shelter of the walls and doorways, the hideous old man seemed like some loathsome reptile, engendered in the slime and darkness through which he moved: crawling forth, by night, in search of some rich offal for a meal. (Dickens 147)

Specific locations throughout London are imagined in this novel to be worlds apart. The East End is a place where dangerous villains hide and capture innocent boys; whereas the West End is the location where benefactors live and use their money and influence to right social ills. And yet, despite these contrasts, on the ground level characters seem to float easily across geographical, social, and ideological borders. The young Oliver is locked in Fagin’s Whitechapel apartment but later escapes; while Fagin moves from his East End home to the Maylie’s middle-class neighborhood, the very space that becomes Oliver’s home later in the novel. If these parts of London carry some of the early qualities that defined the boundaries of the East End, Dickens leads us to wonder about both their porous edges, and the impulse to imagine the East End as a space defined exclusively by the presence of social deviants. In recent years, details about the lives of East End residents have begun to unsettle such depictions, providing reminders of the varieties of people who populated this part of London.[5] Clearly, criminals walked the streets of Whitechapel, as they did throughout London. But East End residents were far from uniform, and prevailing stereotypes, which have a tendency to flatten human character, didn’t adequately speak to their varied identities.

Part of the tension in works like Oliver Twist or in the Cruikshanks’s illustrations in Life in London stem from their one-sidedness. In this period, West Enders increasingly published their accounts of their forays into East London and profoundly shaped what came to be known as “the East End.” The power of these narratives rests on their ability to give the impression of objectivity. Impressions of the East End created by local residents are rarely considered in such constructions of East End life. Arthur Morrison and Israel Zangwill are two noteworthy exceptions to this trend. The fact that they both published their work in the last decade of the nineteenth century might indicate that that earlier periods were less interested either in telling their stories or that readers did not seek stories by locals. Yet, evidence does remain, and offers illuminating accounts that alternately corroborate, resist, or intersect with better known stories of East End crime and poverty. The famous boxer, Daniel Mendoza (1764-1836), for example, published The Art of Boxing (1789) and Memoirs of the Life of Daniel Mendoza (1816) depicting his close ties with the East End Jewish community in the City and ![]() Aldgate, along the East End border lines where he was raised. Maria Polack, an Anglo-Jewish novelist and a resident of Whitechapel, followed Mendoza with details about lavish, well-to-do East London homes and religious practices in her novel, Fiction Without Romance (1830). Polack’s novel focuses primarily on female education and the importance of respecting religious and class differences. Her depictions of London, as well as a number of rural communities in

Aldgate, along the East End border lines where he was raised. Maria Polack, an Anglo-Jewish novelist and a resident of Whitechapel, followed Mendoza with details about lavish, well-to-do East London homes and religious practices in her novel, Fiction Without Romance (1830). Polack’s novel focuses primarily on female education and the importance of respecting religious and class differences. Her depictions of London, as well as a number of rural communities in ![]() Devonshire, appear in this text as spaces where wealthy, middle class, and working poor mingle daily.[6] In the following passage, Polack depicts an East End Sukkah, or the commemorative structure built during the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, which is traditionally decorated with harvest foliage and fruits. Published just seven years before Oliver Twist, Polack offers a striking counter narrative to the well-known image of Whitechapel in Dickens’s work. For Polack the East End was a site not of criminal behavior but of aestheticized religious observance:

Devonshire, appear in this text as spaces where wealthy, middle class, and working poor mingle daily.[6] In the following passage, Polack depicts an East End Sukkah, or the commemorative structure built during the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, which is traditionally decorated with harvest foliage and fruits. Published just seven years before Oliver Twist, Polack offers a striking counter narrative to the well-known image of Whitechapel in Dickens’s work. For Polack the East End was a site not of criminal behavior but of aestheticized religious observance:

About the middle of the yard, a temporary room had been erected, of dimensions sufficiently spacious for the accommodation of a very large party. It was perfect in every respect, except the ceiling, being built totally without a roof; this deficiency was partially supplied by laths, which were place[d] crosswise in the style of lattice work; these were covered outside, by a variety of green foliage, disposed in such a manner, as to render the sky distinctly visible through its branches: but more perfect light was admitted through handsome sash windows, each side of the room having two. These were decorated with silk curtains, of Pomona green, tastefully festooned up with large bouquets of real flowers. The floor was covered with

India matting; cane sophas [sofas] supplied the place of chairs; excepting in the corners of the room, which were filled with garden pots of an immense size, in which were the finest full grown myrtles. In the windows, were placed, orange and lemon trees, which shed an odoriferous fragrance round the room. At the top of the room, against the wall, was placed a small marble slab, on which stood a superb china jar, nearly filled with water; in this, was placed a branch of the palm-tree, the bottom of which was surrounded by sprigs of myrtle and pure willows; near the jar, was placed a small fillagree box, shut. (v.2, 24-5)

Polack was both a novelist and a teacher of music and poetry. It is likely that her novel may have been written to educate young women preparing to enter the marriage market. Her choice to construct an elaborate religious structure in the East End reminds us that not every writer depicted its inhabitants as desperately poor or dangerous, or solely preoccupied with money or food. Indeed, Polack’s images of London’s poor place them throughout the city rather than exclusively in the East End. Simultaneously, her depictions of the East End in the 1820s imagine a culture where different classes and religious groups have opportunities to mix.

Other writers contrast with images by Polack and Dickens by portraying multiple geographic lenses at once. John Hollingshead published a series of articles during one of the coldest winters on record, January 1861, depicting the most economically depressed regions of London. His accounts were first published in the newspaper, The Morning Post with the title, “Horrible London,” and were later revised and republished as Ragged London in 1861. According to Hollingshead, poverty was not an East End problem, but a London problem. As he put it, “The evils of overcrowding in courts and alleys are, unhappily, not confined to the eastern end of the metropolis. There are almost as many dark holes and corners within a few yards of [the wealthier section of London] ![]() Regent street or

Regent street or ![]() Charing Cross, which shelter almost as much sickness, crime, and poverty, as any back hiding-places in [the East End’s] Whitechapel or Bethnal Green” (58). Later in his study, Hollingshead would use his own experiences as a former East Ender to claim authority for his subject. Born in Hoxton, Hollingshead knew well the despair he described in his essays. In his words, “I have lived in it and amongst it ever since I could walk and talk, and I speak with some authority when I say that I know what it is” (112). While the dominant narrative of East End life depicts poverty so abject that no one seems capable of escape, Hollingshed’s history offers a corresponding narrative of possibility. Not only did he leave the East End where he was raised, but Hollingshed emerged a successful writer who later became involved in the London theatre. Thus, his text exemplifies at once characters living in absolute despair and poverty and, through his act of writing and publishing, the potential for finding a better standard of living. Hollingshead’s writing is unusual in its focus on depicting the lives of ordinary citizens, many of whom struggled with poverty. As we shall see, London poverty was not exclusive to the East End. Yet, this part of London was imagined throughout every branch of popular and visual culture as a place uniquely abject, capable of capturing and holding its inhabitants in a seedy underworld of crime and ghettos of stifling poverty.

Charing Cross, which shelter almost as much sickness, crime, and poverty, as any back hiding-places in [the East End’s] Whitechapel or Bethnal Green” (58). Later in his study, Hollingshead would use his own experiences as a former East Ender to claim authority for his subject. Born in Hoxton, Hollingshead knew well the despair he described in his essays. In his words, “I have lived in it and amongst it ever since I could walk and talk, and I speak with some authority when I say that I know what it is” (112). While the dominant narrative of East End life depicts poverty so abject that no one seems capable of escape, Hollingshed’s history offers a corresponding narrative of possibility. Not only did he leave the East End where he was raised, but Hollingshed emerged a successful writer who later became involved in the London theatre. Thus, his text exemplifies at once characters living in absolute despair and poverty and, through his act of writing and publishing, the potential for finding a better standard of living. Hollingshead’s writing is unusual in its focus on depicting the lives of ordinary citizens, many of whom struggled with poverty. As we shall see, London poverty was not exclusive to the East End. Yet, this part of London was imagined throughout every branch of popular and visual culture as a place uniquely abject, capable of capturing and holding its inhabitants in a seedy underworld of crime and ghettos of stifling poverty.

The range of perspectives we encounter from Egan and Cruikshank, Dickens, Polack, and Hollingshead raise important interpretive problems about the way spatial identities are formed through available written records. Moreover, as writers and illustrators created new stories, as the edges of the geographical space shifted, the demographic makeup was also re-organized and given new life by a rising number of immigrants. The building of the docks in the early years of the century inspired a surge of sailors and people from other lands. As time moved forward, events and histories continually re-shaped both the spatial boundary markers of the East End and the lives of those who made it their home. Alan Palmer notes that “The concentration of Ashkenazim [Jewish people from eastern and central Europe] living on the eastern edge of the City was so dense that, before the death of Anne [1714], they formed over a quarter of the population in the parish of ![]() St James’s, Duke’s Place. And there, close to

St James’s, Duke’s Place. And there, close to ![]() Houndsditch and Aldgate, the Ashkenazim established in 1722 their first

Houndsditch and Aldgate, the Ashkenazim established in 1722 their first ![]() Great Synagogue, on the site in Duke’s place itself now covered by the

Great Synagogue, on the site in Duke’s place itself now covered by the ![]() Sir John Cass Foundation School (Palmer 33). Other immigrant groups also made the East End their home, including French Huguenots who arrived in the seventeenth century; Irish groups were well settled by the 1851 census, and later waves of Jewish immigrants fleeing pogroms in eastern Europe arrived through the 1880s. Additional immigration patterns overlapped, bringing Chinese, Malaysian, African-Caribbean, and African peoples to the East End.[7]

Sir John Cass Foundation School (Palmer 33). Other immigrant groups also made the East End their home, including French Huguenots who arrived in the seventeenth century; Irish groups were well settled by the 1851 census, and later waves of Jewish immigrants fleeing pogroms in eastern Europe arrived through the 1880s. Additional immigration patterns overlapped, bringing Chinese, Malaysian, African-Caribbean, and African peoples to the East End.[7]

Images of the East End in the nineteenth century were not just offering the gaze of outsiders looking in on a foreign (to them) place; they were representing perspectives of those who identified as English in the act of shining their floodlights on immigrant communities, many of which were deemed suspicious and uncivilized because they were marked as un-Christian or savage.[8] Marriott notes that the rubric “Outcast London’ best captured the prevailing sense that this part of the metropolis represented an alien presence, close enough to the City to be a threat to its material wealth and way of life, and yet remote from its civilizing influences and inquiring gaze” (Marriott 154). The characterization of the East End as dark, dangerous, and dirty must therefore be read within the context of English fears about the presence of African Caribbeans, Jews, Irish, and other people perceived to be threatening presences because they were not English partly, but also, importantly, because they’d managed to penetrate the very heart of the metropolis.[9]

Pushing Against Constructions of the East End

Quieter, little-known texts from this period often offered voices of dissent that challenge the prevailing grand narratives about the East End. It is here, either in moments of direct dissent or in narrative ambiguity, where the familiar construction of the nineteenth-century East End unravels. The following discussion showcases examples of three such texts: Charles Booth’s Poverty Maps, Arthur Morrison’s fiction and non-fiction, and W. T. Stead’s news stories. Each of these works, in varying ways, either illuminates or challenges the conventional sensationalizing of the East End common among popular nineteenth-century writing. Thus, even as such popular modes were proliferating in this period, a persistent strand of resistance to that stereotype emerged simultaneously. These counter or competing narratives, many of which are just coming to light, prompt us to consider how space is imagined by those who lived in or visited the East End. Yet, the range of views should also serve as a reminder that space can never be reduced to a single range of voices or visions. To understand how the East End was imagined, why it held such a privileged place in the literature of London in this period, we must consider a diverse assortment of views that will never line up as universal or complete. Yet, through this tangled array of visions we can begin to trace tensions that animated the profusion of writing and interest in the East End in this period.

In 1885, just a few years before the Ripper murders, Charles Booth, a wealthy Victorian businessman, read with discomfort the results of a survey of working-class London neighborhoods published in the Pall Mall Gazette. The survey’s shocking conclusions were that “one out of four Londoners lived in abject poverty” (xvii). Booth was suspicious of these findings. Albert Fried and Richard M. Elman explain, “He thought they were inspired by religious or political ideology, or by the desire for sensationalism, rather than by a concern for the truth” (xvii). In response, Booth conducted another survey to investigate. To this end, he gathered reports, statistics, and other official records in an effort to discern the truth about the plight of London’s poor. The results of his study Life and Labour of the People appeared in 1889 and covered only the East End of London. Booth followed up with the publication of now-famous maps that color-coded London’s streets to enable viewers to visualize—albeit from another kind of detached perspective—a street-by-street class structure.[10] Booth’s goal was to provide statistical accuracy to a foregone conclusion: London’s East End was dominated by abject poverty and despair. His results, however, challenged those assumptions in myriad ways.[11]

William Fishman explains that while Booth’s maps depict a large population of people struggling to survive, they simultaneously show that “65 per cent [of the population of the East End] lived above the poverty line” (50). More recently, John Marriott adds,

We must [. . .] exercise a degree of caution in viewing nineteenth-century East London as a place of unmitigated poverty and desolation [. . . .] Booth found that approximately half of the adult males were in regularly paid occupations described as skilled, professional or merchant, while less than ten per cent were in irregular, casual employment, the remainder being semi-skilled. East London in the late nineteenth century was therefore dominated for the most part by skilled and semi-skilled workers and their families, who tended to determine the course of industrial struggle; they also inhabited and largely controlled the area’s cultural landscape. There were members of the labour force who possessed genuine levels of skill, and could command regular employment providing them with relatively comfortable means [. . . .] [H]istorical accounts of East London have neglected this stratum of skilled labour, and yet is it one which needs to be considered in order to provide a more complete—and complicated—picture of the social composition of the area. (119)

Fishman and Marriott do not deny that poverty was a major problem in the East End in this period. Their point rather is that “the levels of poverty in Whitechapel compared favourably with districts such as ![]() Southwark, Greenwich and

Southwark, Greenwich and ![]() Bermondsey” (Marriott 151).[12] We may wonder, then, why these other areas have not been sensationalized in the same manner as depictions of the nineteenth-century East End. And how might we begin to register the complexity of the East End in light of both a discourse constructing the East End as a site of universal darkness, foreignness, and danger and a space where locals pushed against such grand narratives?

Bermondsey” (Marriott 151).[12] We may wonder, then, why these other areas have not been sensationalized in the same manner as depictions of the nineteenth-century East End. And how might we begin to register the complexity of the East End in light of both a discourse constructing the East End as a site of universal darkness, foreignness, and danger and a space where locals pushed against such grand narratives?

Arthur Morrison is one such example of a writer born in the East End who later became wealthy and moved far from London. Much of Morrison’s writing focused on his knowledge of the East End world and its public image. The following passage, published as “A Street” in Macmillan’s Magazine in 1891, enfolds a description and critique of popular myth-making about the East End:

It is in the East-end. There is no need to say in the East-end of what. The East-end is a vast city, as famous in its way as any city men have built. But who knows the East-end? It is down through

Cornhill and out beyond

Leadenhall Street and

Aldgate pump, one will say; a shocking place, where he went once with a curate. An evil growth of slums which hide human creeping things; where foul men and women live on penn’orths of gin, where collars and clean shirts are not yet invented, where every citizen wears a black eye, and no man combs his hair. Our street is not in a place like this. The East-end is a place, says another, populated by the unemployed. The unemployed are a race whose token is a clay pipe, and whose enemy is soap.

Now and again they migrate bodily to Hyde Park with banners, and furnish surrounding police courts with disorderly drunkards. Still another knows the East-end only as the place whence come begging letters; where coal and blanket funds are in a state of permanent insolvency, and somebody is always wanting a day in the country. Everybody has his own notion of the East-end,—usually nothing but a distorted conception of some incidental feature of the place. There are foul slums in the East-end of course, just as there are in the West-end; there is want and misery in the East-end, just as there is wherever men and women gather together to fight for food and a roof; but it is not always of a spectacular sort. (Morrison 460)

As Morrison details the proclivity toward seeing people from the East End as “human creeping things,” he simultaneously underscores the fact that this is a creation of those who try and fail to capture the East End in popular discourse. One such view believes the East End is a space somewhere in the vicinity of Aldgate pump. Another sees it exclusively and reductively as the place of unemployed who walk through the streets collar-less. A third “knows” the East End as the location where people live in defiance against soap. “Everybody has his own notion of the East-end,” Morrison concludes, but these are distorted perspective that fail to register the complexity of life on the streets of the East End.

Morrison’s account, while uniquely critical of the body of writing produced about the East End in his lifetime, is part of a tradition of resistance to the notion that the East End can be easily qualified by tales of horror. Hard-to-pin-down narrators frequently equivocated in their accounts of the East End, landing somewhere between curiosity, confusion, and distrust of their East End subjects. In many cases such accounts present a kind of relative, or relational tension that worked to create a divide between East and West End cultures. In so doing, these writers read alongside sensational accounts of the East End expose, on the one hand, the existence of both dismissive and respectful views of East End life, and, on the other, the prominence of complicated over-determined assumptions that the East and West were essentially separate spheres—one that was universally wealthy and another desperately poor.

Evidence of this kind of relational tension can be found in W. T. Stead’s (in)famous exposé of child prostitution in The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon, published in June of 1885 in the Pall Mall Gazette. Stead begins this work with a “Frank Warning” to readers, a short introductory piece published the day before the appearance of The Maiden Tribute, in which Stead explains, “The public, it is said, is not interested in the subject [of prostitution]” and the Criminal Law Amendment Bill is thus in danger of being “abandoned” by the government (51). Stead’s goal is not simply to expose the immorality of child prostitution, but to generate interest among readers in passing this bill, which would raise the age of consent for sexual acts from thirteen to sixteen. In five articles, Stead inventoried the intimate details of young girls—ages four to fourteen—who were abducted, drugged, raped, and/or sold into a life of prostitution, sometimes even by members of their own family desperate for money or for one less mouth to feed. In trying to criminalize the vices of the rich, Stead argues that the criminal figure is not exclusively a product of the dark seedy streets of Whitechapel. Rather, one of the worst criminal figures in Stead’s narrative lives in middle-class or well-to-do homes in West London. Rather than read the social and moral problems in London as the result of East End criminal behavior, in The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon Stead suggests that the horrible social deviants are West End men encroaching on innocent girls throughout the metropolis.

The first installment of The Maiden Tribute appeared on Monday, 6 July 1885. It included an interview with an unnamed East End man under the sub-heading “Confessions of a Brothel Keeper.” Readers learn that this man “formerly kept a noted house on Mile-End road, but who is now endeavouring to start life afresh as an honest man” (67). In his statement, this man explains:

[t]he East is the great market for the children who are imported into West-end houses, or taken abroad wholesale when trade is brisk. I know of no West-end houses, having always lived at Dalston or thereabouts, but agents pass to and fro in the course of business. They receive the goods, depart, and no questions are asked.” (Stead 69)

This same man proceeds to offer details about his former East End brothel, and about the movement of girls—“Maids, as you call them—fresh girls as we know them”—who are lured from East London and then moved to brothels in West London. In a subsequent section titled, “A Dreadful Profession” included in the same day’s article, Stead describes his conversation with a “highly respectable midwife” to whose house “children were taken by procurers to be certified as virgins before violation, and where, after violation, they were taken to be “patched up,” and “if necessary given abortions” (74). Stead adds, “the existence of the house was no secret” (74).

Such stories are disturbing enough, yet what adds strangeness to these accounts is Stead’s choice to frame the problem of child prostitution in London as one with East and West counterparts. Why mention London geography at all? If the goal is to change British law, and to show that child prostitution is a problem everywhere in the city of London, what is the point of delineating East from West—especially when both play an active role in the procurement and abuse of young girls? We might, however, ask this question a different way: What does Stead’s attentiveness to London geography enable him to say about London vice? What work does this division of London accomplish or allow for in The Maiden Tribute‘s rhetoric?

Robert L. Patten offers one answer to this problem, suggesting that “A hermeneutics of literary geography helps to recover the aesthetics […] which embody ways a culture organizes itself [and] allows us to ask why a place is made, why it is a place to start from or come to, and why, because of those starting and ending points, the spaces and journeys signify in particular ways” (192). According to Patton, literary geography is not a meager reference to the location of plot action; rather, both setting and place function centrally as part of a work’s aesthetics, of its political engagements, and in the significance of what literary texts can say and mean by alluding to place. This point becomes all too clear in Stead’s subtle challenge to simplified constructions of a refined West End and a socially deviant East End. In the subsequent sub-section titled, “Juvenile Prostitution in the East and West,” Stead makes the following pronouncement: “In the East-end of London vice is much more natural than in the West” (120). The passage continues by elaborating on the essential differences in the way East Enders and West Enders engage in the culture of prostitution. He explains,

the taste for extreme youth does not seem to have developed in the crowded East. Here and there are cases, and there are vast strata where the children cohabit from preposterously early years, but that is quite distinct from prostitution. In the most fashionable houses of ill fame, [located in the East End] such as Mrs. Jeffries’s, Mrs. B——–‘s, J———‘s, and others, any stranger ordering young children of very tender age would be looked at askance. These things are only done for old customers. (120)

Stead’s East End has a decided disadvantage in its natural proclivity for vice; the upside is that those who hire prostitutes at least still prefer adults over children. He neglects to elaborate on what he means by “vice is more natural” in the East, but earlier discussions concerning the procurement of young girls in the East would suggest that economic forces are at work in this characterization. Hence, it is more natural that someone struggling to feed their children might sell one into prostitution. Yet, Stead’s continuing articles suggest that there’s more to it than that. In the interview with the West End patcher, who lives in a home described as “imperturbably respectable in its outward appearance, apparently an indispensable adjunct of modern civilization” (74), Stead alludes to the kind of problem taking place in the West End. From the patcher, we learn about the following:

“Mr. —— is a gentleman who has a great penchant for little girls. I do not know how many I have had to repair after him. He goes down to the East-end and the City, and watches when the girls come out of shops and factories for lunch or at the end of the day. He sees his fancy and marks her down. It takes a little time, but he wins the child’s confidence. One day he proposes a little excursion to the West. She consents. Next day I have another subject, and Mr. —- is off with another girl.” (Stead 75)

Although the West End includes people like the patcher who are “respectable” and serve as “adjuncts” of “modern civilization,” we also find men like MR. —— who appear gentlemanlike on the surface, but prey upon East End girls in private. In effect, then, while Stead claims that it is natural for East Enders to engage in prostitution, when West Enders do the same it’s a sign that they are not holding up the values of modern civilized society. Seemingly offhand references to the places where girls are procured or where they go to be “patched up” play a powerful role in enabling Stead to succeed in getting the Criminal Law Amendment Bill passed. Yet, in the end, The Maiden Tribute created a version of London out of a number of competing discourses. The reductive East and West moral or economic division may be at work, but it is complicated by other resistant narratives that contradict one another in this coverage of child prostitution. In this way, they function as an expression not of a separation but of an undercurrent of relations linking East and West ends of London even in texts that would seem to be otherwise invested in keeping them separate.

Conclusion: The Myth of the Nineteenth-Century East End

On the eve of the 2012 Olympics in the East End of London, a NY Times article described this area as “A sprawling area known for its artists, anarchists and immigrants.” And as a place that now feels “light years away from central London, and totally self-sufficient, thanks to a host of [new] enticing restaurants, shops, markets and hotels.”[13] Another Olympics-related article published in the LA Times similarly evoked nineteenth-century discourse on the East End:

This once was a grimy industrial zone where factories brewed ale and belched smoke, where 17th century French Huguenot immigrants were followed by 19th century Irishmen and Jews from throughout Europe, who were followed by 20th century Bengali immigrants, whose curry shops remain[. . . .] The East End wasn’t just poor and dangerous in the bad old days; it was inspirationally poor and dangerous. Ikey Solomon, the 19th century criminal who inspired Charles Dickens’ Fagin, had his shop here on

Bell Lane. The unfortunate Joseph Merrick was displayed as the Elephant Man on Whitechapel Road and died after years in residence at the

London Hospital on the same thoroughfare. Jack the Ripper stalked victims here and is said to have patronized the

Ten Bells pub, still in business at 84 Commercial St. opposite the

Old Spitalfields Market. (Christopher Reynolds n.p.)

These descriptions of the East End deserve our attention not just because they are reductive and misleading but because of the use of a pernicious nineteenth-century cultural legacy. Egan, Dickens, and many other outsiders visiting and recording their encounters in the East End helped create a narrative that is still very much in circulation. And while their view may indeed accurately describe what they saw, as I have tried to suggest, it represents only their perspectives gazing on subjects somewhat alien to them. Contrasting accounts by writers such as Mendoza, Polack, Hollingshead, Stead, and Morrison do not cohere with these formulations, and remind us to pause over accounts that pigeonhole the East End as a uniform space, characterized by universal cultural and economic depravity and set against an equally reductive portrait of West End wealth.

Clive Bloom is right to note that these narratives have cast a long shadow over the construction of the East End. He explains, the “East End of London becomes at once truncated into the ‘East End’ and that in turn is truncated into a cobbled street, a blind alley, a gaslit corner. The real and the tangible of history become the fractured scenario of nostalgia for history, a ruined memory of a landscape now reduced to its significant effects, glimpses of a lost place that never quite existed” (Bloom 239). To call the East End a lost space or a ruined memory does not suggest its reputation is untrue and therefore unworthy of our attention. Rather, it is as a construction that we must weigh accounts of the East End. The goal should never be to replace one totalizing narrative with another, but to approach the study of space in a way that opens up new views and questions about its complexity and dynamism. To see a place as any single entity is to miss seeing it as live, continually made new by the interplay of human and structural features that give it life and identity. The East End emerged as a particular place in the nineteenth century not through a singular, popular narrative thread that’s been passed down to us, but through a range of competing or disparate narratives. Read alongside one another, writing about the nineteenth-century East End showcases how and why place matters to those who live in it, visit it, and attempt to use words, images, and narratives to define what they see. Yet, this range of views also helps to recover features of the East End’s animating forces otherwise occluded by the bull’s-eye lantern.

published January 2016

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Kaufman, Heidi. “1800-1900: Inside and Outside the Nineteenth-Century East End.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

A new and accurate description of the present great roads and the principal cross roads of England and Wales, commencing at London, and continued …. London, printed for R. and J. Dodsley, 1756. Eighteenth-Century Collections Online. Accessed 5 March 2015. Web.

Archenholz, Johann Wilhelm von. A picture of England: containing a description of the laws, customs, and manners of England. Interspersed with curious and interesting Anecdotes Of Many Eminent Persons. Trans. from the original German of W. de Archenholtz. Formerly A Captain In The Prussian Service. A new translation. London, 1797. Eighteenth-Century Collections Online. Accessed 5 March 2015. Web.

Besant, Walter. All Sorts and Conditions of Men. Ed. and Intr. by Kevin A. Morrison. Brighton: Victorian Secrets, 2012. Reprint from 1882. Print.

Bloom, Clive. “Jack the Ripper—A legacy in Pictures.” Jack the Ripper and The East End. Intr. Peter Ackroyd. London: Chatto & Windus and the Museum in Docklands & Museum of London, 2008. 239-267. Print.

Cox, Nancy. London’s East End: Life and Traditions. London: Seven Dials, Cassell & Co., 2000. Reprint from London: George Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1994. Print.

Curtis, L. Perry, Jr. Jack the Ripper and the London Press. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 2001. Print.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist: Or, the Parish Boy’s Progress. New York: Penguin, 2003. Print.

—. Our Mutual Friend. Ed. Adrienne Poole. New York: Penguin, 1988. Print.

Egan, Pierce. Life in London. New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1904; reprinted from, Life in London; Day and Night Scenes of Jerry Hawthorn, Esq. and his elegant friend Corinthian Tom, accompanied by Bob Logic, the Oxonian, in their Rambles and Sprees through the Metropolis, 1821. Google Books. Accessed 5 March 2015. Web.

Egan, Pierce. Life in London; or, The day and night scenes of Jerry Hawthorne, esq., and his elegant friend Corinthia Tom, accompanied by Bob Logic, the Oxonian, in their rambles and sprees through the metropolis. London: Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, 1821. Print.

Fishman, William. East End 1888. Nottingham: Five Leaves Press, 2005 (reprint). London: Gerald Duckworth & Co., Ltd. 1988. Print.

Fried, Albert and Richard M. Elman. “Introduction.” Charles Booth’s London: A Portrait of the Poor at the Turn of the Century, Drawn from His “Life and Labour of the People in London”. Ed. Albert Fried and Richard M. Elman. New York: Pantheon Books, 1968. Print.

Gerzina, Gretchen Holbrook. Black London: Life Before Emancipation. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 1995. Print.

Gilbert, Pamela K., ed. Imagined Londons. New York: State U of New York P, 2002. Print.

—. Mapping the Victorian Social Body. New York: State U of New York P, 2004. Print.

Gilman, Sander. The Jew’s Body. New York and London: Routledge, 1991. Print.

Hollingshead, John. Ragged London in 1861. Intr. Anthony S. Wohl. London and Melbourne: Everyman’s Library, 1986. Print.

Kaufman, Heidi, “England’s Jewish Renaissance: Maria Polack’s Fiction Without Romance (1830) in Context” in Romanticism/Judaica: A Convergence of Cultures. Ed. Sheila A. Spector. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2011. 69-83. Print.

Keating, Peter, Ed. Into Unknown England: 1866-1913. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1976. Print.

Kershen, Anne J. Strangers, Aliens and Asians: Huguenots, Jews and Bangladeshis in Spitalfields 1660-2000. London and New York: Routledge, 2005. Print.

King-Dorset, Rodreguez. Black Dance in London, 1730-1850: Innovation, Tradition and Resistance. Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2008. Print.

Koven, Seth. Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics in Victorian London. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2004. Print.

Marriott, John. Beyond the Tower: A History of East London. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 2011. Print.

McLaughlin, Joseph. Writing the Urban Jungle: Reading Empire in London from Doyle to Eliot. Charlottesville: U of Virginia P, 2000. Print.

Mogg, Edward. Mogg’s Strangers Guide to London: Exhibiting all the Various Alterations & Improvements Complete to the Present Time. Special Collections and Archives, DePaul University Library: http://digicol.lib.depaul.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p16106coll1/id/256. Accessed 5 March 2015. Web.

Morrison, Arthur. “A Street” Macmillan’s Magazine LXIV (1891): 460-3. Print.

Nead, Lynda. Victorian Babylon: People, Streets and Images in Nineteenth-Century London. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 2000. Print.

Newland, Paul. The Cultural Construction of London’s East End: Urban Iconography, Modernity and the Spatialisation of Englishness. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2008. Print.

Nord, Deborah Epstein. Walking the Victorian Streets: Women, Representation, and the City. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1995. Print.

Palmer, Alan. The East End: Four Centuries of London Life. London: John Murray Publishers Ltd., 2004. Print.

Patton, Robert L. “From House to Square to Street: Narrative Tranversals.” Nineteenth-Century Geographies: The Transformation of Space from the Victorian Age to the American Century. Ed. Helena Michie and Ronald R. Thomas. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2003. 191-206. Print.

Polack, Maria. Fiction Without Romance: or The Locket-Watch. 2 Vols. London: Effingham Wilson, 1830. Print.

Reynolds, Christopher. “London’s East End, an Olympics Alternative.” Los Angeles Times. 4 December 2011. Accessed 17 March 2016. Web.

Riis, Jacob. How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. 1971. Print.

Roemer, Nils. “London and the East End as Spectacles of Urban Tourism.” The Jewish Quarterly Review 99.3 (Summer 2009): 419-20. Print.

Ryder, Stephen P. “Illustrated Police News 8 September 1888.” Casebook: Jack the Ripper. Accessed 5 March 2015. Web.

Sicher, Efraim. “The ‘Attraction of Repulsion’: Dickens, Modernity, and Representation.” A Mighty Mass of Brick and Smoke: Victorian and Edwardian Representations of London. Ed. Lawrence Phillips. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2007. 35-60. Print.

Stead, W. T. The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon. Ed. Antony E. Simpson. Lambertville, NJ: The True Bill Press, 2007. Print.

The London Guide: describing the public and private buildings of London, Westminster, & Southwark; embellished with an exact plan of the metropolis, and an accurate map twenty miles round. To which are annexed, several hundred hackney coach fares, the rates of watermen, &c. London : Printed for J. Fielding, [1782?]. Eighteenth-Century Collections Online. Accessed 5 March 2015. Web.

Walkowitz, Judith. City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1992. Print.

Wolfreys, Julian. Writing London. 3 vols. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1998, 2004, 2007. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] I borrow this expression from Jacob Riis’s work, How the Other Half Lives (1890). Riis lived in poverty as a child, and as an adult police officer used his camera to document and draw public attention to extreme poverty in New York’s Lower East Side.

[2] Roemer makes an important point here about perspective in London. Numerous recent works have, similarly, made key contributions to this discussion. In addition to those sources mentioned in this essay, the following recent texts offer important ways of reading perspective, space, and memory in Victorian London: Julian Wolfreys; Pamela K. Gilbert Imagined Londons and Mapping the Victorian Social Body.

[3] Rodreguez King-Dorset explains that in this period “[t]he great majority of blacks in London came from the Caribbean” (82). According to Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina, “Up until 1783 Britain’s black population consisted mainly of servants and former servants, musicians and seamen. Suddenly, with the end of the war with America, England felt itself ‘overwhelmed’ by an influx of black soldiers who had served the loyalist cause and who crossed the Atlantic for their promised freedom and compensation” (136).

[4] It’s important, as I argue in this essay, to see each depiction of London within a larger trajectory of narratives that tried to define this space. Contemporary writers have extended such details in their published descriptions of the East End. Nancy Cox, for example, describes the East End in the following way:

The oldest document held by Tower Hamlets Local History Library is the lease of a property in an aptly-named Pillory Lane, East

Smithfield, dated 1574. In Medieval and early modern times the Tower’s hinterland throbbed with low life; it grew up as the service area for the castle, a traditional way for medieval towns and suburbs to develop. Houses and workshops, brewaries and alehouses, farms and garden plots gathered around inside the walls and two great monastic houses serviced the needy and kept order. [. . .] Already, in medieval times, this was a true East End, stuffed with gambling dens and brothels and alive with foreign immigrants, with do-gooders struggling to clean up the place and help the needy. (55)

While such descriptions contribute to a familiar stereotype, I suggest that we call into question this notion of a “true” East End characterized by gambling dens and brothels. Certainly they existed, as they did in other parts of London. And, moreover, not everyone living in the East End participated in the same cultural activities. Gambling and brothels are therefore only part of the story of the East End.

[5] For a fuller discussion of Maria Polack’s novel, see Heidi Kaufman, “England’s Jewish Renaissance: Maria Polack’s Fiction Without Romance (1830) in Context.”

[6] Paul Newland includes a helpful discussion of East End ethnic, national, and religious diversity in this period. He notes, “East London’s population is, and has been, one of the most ethnically diverse in England.” See his Introduction and Chapter 1 for further details. See also Anne J. Kershen’s important work on the history of immigration in Strangers, Aliens and Asians: Huguenots, Jews and Bangladeshis in Spitalfields 1660-2000. The diversity of immigrant communities was certainly part of the way the East End came to be understood in this period. However, other noteworthy events simultaneously played a part in the sensationalism that culminated with the Whitechapel murders: the cholera epidemics of 1832 and 1866, the birth of William Booth’s Salvation Army, and the rise of unionism led by prominent new women such as Annie Besant, Beatrice Potter Webb, and Eleanor Marx. Following the publication of Walter Besant’s, All Sorts and Conditions of Men (1882), The People’s Palace was built aimed at providing a cultural outlet for the working poor. Money to support this venture came from the West End, like a good deal of charity aimed at helping the East End poor. In sum, the East End came to be known as not only poor and criminal, but as a place with charity efforts, rising socialist activities, and women’s activism.

[7] In her brilliant study of Victorian visual culture, Lynda Nead notes of the Jewish ghetto in Hollywell Street that “There was a clear correspondence between the definition of space and race in this period. Jewish space is black, ugly and airless. The unkempt exterior world of the Jewish street terminates in the disturbing, tomb-like interiors of their shops. Jewish London is dangerous and deceptive, and the ghetto, along with the rest of Holywell Street’s impurities, must come down to make way for the modern metropolis” (177).

[8] Marriott has argued persuasively,

Whitechapel—and, by extension, East London—was created as a site of fear, loathing and moral desolation. The events of 1888 [The Whitechapel Murders] served merely to focus and hence greatly intensify the anxieties of respectable opinion about the state of the poor, and the threat they posed to the future of the imperial race. . . . (154)

This is a point that becomes clear when we consider the Whitechapel investigation that targeted Jewish men in particular. See Sander Gilman’s, The Jew’s Body, particularly chapter 4, “The Jewish Murderer: Jack the Ripper, Race, and Gender.”

[9] A digital reproduction of these maps can be found on the following website: ![]() London School of Economics & Political Science, Charles Booth Online Archive (accessed 5 March 2015). Booth’s maps have remained a major touchstone for scholars of London. The Charles Booth Online Archive not only reproduces the color-coded maps, but also provides Booth’s key delineating the classes of people living in each neighborhood. In this case, the poor were not merely needy but are described as “Vicious and semi-criminal.”

London School of Economics & Political Science, Charles Booth Online Archive (accessed 5 March 2015). Booth’s maps have remained a major touchstone for scholars of London. The Charles Booth Online Archive not only reproduces the color-coded maps, but also provides Booth’s key delineating the classes of people living in each neighborhood. In this case, the poor were not merely needy but are described as “Vicious and semi-criminal.”

[10] Charles Booth also wrote and hired a team of others to write journals depicting interviews and observations of the London poor. These records have been digitized by the London School of Economics: http://booth.lse.ac.uk/.

[11] Keating makes a similar point: The results of Booth’s study showed that “35.2 per cent of the East London population lived in poverty, and, what was even more disturbing considering that the East End was supposed to be a special case, later investigation gave the corresponding figure for London as a whole as 30.7 per cent” (Keating 25).

[12] NYTimes travel section, Sunday, 5 September 2010, TR 9.