Abstract

Proposed in 1780 to “suppress” the rise of Dissenting and freethinking societies, the Sunday Observance Act was passed in 1781 and adopted across Britain that year. In seeking to encourage Sunday worship, the new law aimed to curb Sunday trading and to prevent the public on such days from visiting parks, museums, zoos, theaters, meeting-houses, and concert halls. The interest of this essay lies in the cultural effects of such legislation, as well as in the figure who proposed it, Bishop Beilby Porteus, and the freethinking philosopher, William Nicholson, who is said to have challenged Porteus and Britain’s episcopacy by detailing the law’s and the Bible’s inconsistencies. The pamphlet attributed to Nicholson, though its authorship remains contested, is called The Doubts of Infidels.

The “Act for Preventing Certain Abuses and Profanations on the Lord’s Day, Called Sunday” bears more than a striking name. For more than a century and a half, while Britain was industrializing and undergoing numerous democratic reforms, the 1781 observance law was responsible for closing each Sunday not just the nation’s theaters and taverns but also its libraries, museums, zoos, public gardens, and of course its shops. In 1831, the Lord’s Day Observance Society was formed to help ensure the law’s application across the country, including to end Sunday trading, but in May 1894 a National Federation of Sunday Societies was established in ![]() Leeds in an effort to “remove all [such] vexatious restrictions” (Judge 1). Despite vocal criticism also in

Leeds in an effort to “remove all [such] vexatious restrictions” (Judge 1). Despite vocal criticism also in ![]() Scotland and

Scotland and ![]() Wales, where the law was equally far-reaching, even modest reform took another four decades. The 1932 Sunday Entertainment Act made it possible once more for the British public to visit museums, zoos, and picture galleries on Sundays, but it wasn’t until 1972, remarkably, with passage of the Sunday Theatre Act, that British theaters were once more able to open and hold performances legally on such days.

Wales, where the law was equally far-reaching, even modest reform took another four decades. The 1932 Sunday Entertainment Act made it possible once more for the British public to visit museums, zoos, and picture galleries on Sundays, but it wasn’t until 1972, remarkably, with passage of the Sunday Theatre Act, that British theaters were once more able to open and hold performances legally on such days.

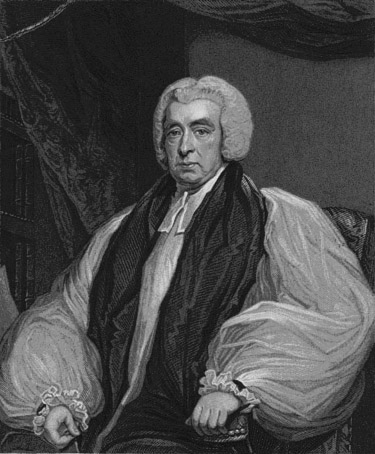

Figure 1: Print of engraving of Beilby Porteus, Bishop of London (1731-1809). The engraving is by H.Meyer after J. Hoppner R.A.

According to Bishop Porteus, “the beginning of the winter of 1780 was distinguished by the rise of a new species of dissipation and profaneness.” On Sundays, he noted with dismay, groups across London would assemble in public meeting rooms, adopting names such as “Christian Societies, Religious Societies, [and] Theological Societies” (qtd. in Hodgson 72). Though meeting “under pretence of inquiring into religious doctrines, and explaining texts of holy Scripture,” he claimed, they were “unlearned and incompetent to explain the same” (qtd. in Cox 2:234). Porteus, who was quick to group freethinkers with devout nonconformists in his opposition to both and who has since been noted as a likely prototype for Mr. Collins in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813), argued that such discussions “were calculated to extinguish every religious principle” and thus “threatened the worst consequences to public morals” (qtd. in Hodgson 74). They “gave offence … to every man of gravity and seriousness,” he warned, “several of whom I have heard speak of [them] with abhorrence.” Foreigners apparently had been “shocked and scandalized . . . , considering it a disgrace to any Christian country to tolerate so gross an insult on all decency and good order” (qtd. in Hodgson 72-74).

In the interests of maintaining “good order,” Porteus sought the aid of Parliament to crack down on religious dissent and criticism, but passage of his bill was not smooth. Several members of Parliament “violently opposed” it, he recalls in his biography, uncovered several years later, and heated discussion also broke out in the House of Lords, though it ultimately passed “without a division” (qtd. in Hodgson 76). The law’s sweeping powers also sparked criticism beyond Parliament, including in the publication of an articulate rebuttal, an anonymous pamphlet called The Doubts of Infidels: Queries Relative to Scriptural Inconsistencies & Contradictions (1781). Its author called himself “A Weak but Sincere Christian” who was submitting his questions to “The Bench of Bishops for Elucidation” (Anon. i). As a self-described infidel, however, the author captured both the word’s flavor of heresy and its suggestion of infidelity (infidel comes to us via the Old French infidèle). Bristling with anger, he was doubtful of the bishops’ ability to answer pages of well-documented concerns about scriptural inconsistency, which he detailed for them chapter and verse.

Though its authorship is still contested, the pamphlet has been attributed to William Nicholson (1753-1815), a renowned London chemist and philosopher, and it begins as brilliantly controlled satire: “An act of parliament is,” he writes, “an excellent engine for producing that kind of uniformity of opinions, which consists in holding the tongue. . . . It is carrying the notion of liberty too far to suppose, because we are free-born Englishmen, that we may choose our own faith and go to heaven our own way!” (v-vi).The pamphlet attributed to Nicholson was not the only one to criticize the new law; dozens of similar ones appeared in the same years, railing at both the law and ecclesiastical power more generally (see Royle; Lane). Still, the intervention—exemplary in its precision and influence—helps convey how freethinkers in the 1780s fostered a culture of doubt and unbelief that, among other things, made it easier for Victorian liberals to argue for religious moderation and against religious extremism.

In his Literature of the Sabbath Question (1865), for instance, author Robert Cox noted that the law was widely perceived mid-century as a “barrier” to public learning and relaxation, as well as one that “prevents the admission of the public on Sundays to the Crystal Palace at ![]() Sydenham” (2:239). (For a BRANCH essay on Sydenham, see Anne Helmreich, “On the Opening of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, 1854.″) In his famous treatise On Liberty (1859), John Stuart Mill went further, complaining that zealots were continuing to cite the 1781 law in their “repeated attempts to stop railway travelling on Sundays” (159). He called such obstructions a type of “religious bigot[ry]”—a form of harassment against doubters, freethinkers, and unbelievers that stemmed, he wrote, from “the notion that it is one man’s duty that another should be religious, . . . a belief that God not only abominates the act of the misbeliever, but will not leave us guiltless if we leave him unmolested” (151).

Sydenham” (2:239). (For a BRANCH essay on Sydenham, see Anne Helmreich, “On the Opening of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, 1854.″) In his famous treatise On Liberty (1859), John Stuart Mill went further, complaining that zealots were continuing to cite the 1781 law in their “repeated attempts to stop railway travelling on Sundays” (159). He called such obstructions a type of “religious bigot[ry]”—a form of harassment against doubters, freethinkers, and unbelievers that stemmed, he wrote, from “the notion that it is one man’s duty that another should be religious, . . . a belief that God not only abominates the act of the misbeliever, but will not leave us guiltless if we leave him unmolested” (151).

As I demonstrate more fully in a longer history of freethought and agnosticism, the push for secularism and religious moderation that Mill and his contemporaries encouraged—an impetus including novelist and essayist George Eliot, sociologist-philosopher Herbert Spencer, and biologist Thomas H. Huxley—grew from not just historical criticism of the Bible and well-reasoned doubts about Biblical infallibility but also a principled liberal argument about the right to unbelief as well as belief. Such intellectuals saw the “Act for Preventing Certain Abuses and Profanations on the Lord’s Day, Called Sunday” not as a way of preserving the Sabbath, as its supporters claimed, but, as Bishop Porteus had candidly explained, as a way of tightening social control, “suppressing” freethought, and outlawing unapproved Sunday worship (qtd. in Hodgson 75). In their stringent objections to all such restrictions, the freethinkers helped to recast the debate and, in turn, to alter public opinion. Their well-stated objections acted as a brake on the zealous extremes to which some Victorians, in their attempt at restricting travel and even museum visits on Sundays, made clear they were still prone.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published May 2012

Lane, Christopher. “On the Victorian Afterlife of the 1781 Sunday Observance Act.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

Anon. [Attributed to Nicholson, William]. The Doubts of Infidels; or, Queries Relative to Scriptural Inconsistencies & Contradictions, Submitted for Elucidation to the Bench of Bishops, &c. &c. by a Weak but Sincere Christian. 1781. London: R. Carlile, 1819. Print.

Cox, Robert. The Literature of the Sabbath Question, in Two Volumes. Edinburgh: MacLachlan and Stewart, 1865. Print.

Hodgson, Robert. The Life of the Right Reverend Beilby Porteus, D.D., Late Bishop of London. London: Cadell and Davies, 1813. Print.

Judge, Mark H. (Hon. Sec.). “National Federation of Sunday Societies,” instituted in Leeds, May 7, 1894, concerning Statute 21 George III, Chapter 49. Federation Papers No. 3. London: Pall Mall, 1894.

Lane, Christopher. The Age of Doubt: Tracing the Roots of Our Religious Uncertainty. New Haven: Yale UP, 2011. Print.

Mill, John Stuart. On Liberty. 1859. London: Penguin, 1982. Print.

Royle, Edward. Victorian Infidels: The Origins of the British Secularist Movement, 1791-1866. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974. Print.

“Sunday Theatre Act 1972.” legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives, n.d.. Web. 17 December 2011.