Abstract

Parliament repealed the Corn Laws, the legislation that controlled the importation of grain, in 1846. Commercial and industrial interests had been advocating the repeal for decades, claiming that the Corn Laws benefited the landed aristocracy at the expense of the middle and working classes. Free traders called for an economic system under which the state would no longer protect landowners. Heated public debates on the Corn Laws, which addressed wages, taxes, and rents, often appealed to religious and moral values, exploring whether free trade was compatible with patriotism and traditional family structures. For the Victorians, national self-reliance and the cosmopolitan spirit of cooperation were both hanging in the balance as Parliament debated the preference for domestic grain.

Looking back to the early 1830s, the narrator of George Eliot’s Felix Holt(1866) highlights how much change has taken place in just a few decades: “In those days there were pocket boroughs, . . . unrepealed corn-laws, three-and-sixpenny letters” (3). As the retrospective narration suggests, by the 1860s, the Corn Laws belonged to a bygone past. Their repeal in 1846 marked the end of an era, delineating the boundary between what counted as the past and the present. Why did the Corn Laws, a piece of legislation regulating the importation and exportation of grain, come to have such a hold on the national memory? Why did the repeal of the Corn Laws become an emblem of historical transformation? The most direct answers to these questions concern economic developments. The Corn Laws protected the landed interest by prohibiting the importation of grain when prices in the domestic market were high. The resulting price levels were injurious to the commercial and industrial interests as well as to the poor because wages were dependent on the price of grain. In the decades preceding the repeal, the most vociferous opponents of the Corn Laws were merchants and manufacturers who sought to weaken the influence of the aristocracy. From the perspective of the middle class, the repeal marked an auspicious shift in the balance of power between classes.

Debates over the preference for domestic corn evoked larger questions about the limits of centralized authority and the meaning of loyalty. Those who supported the repeal claimed that free trade would allow the exercise of individual liberty and render the nations of the world interdependent, thereby cultivating feelings of sympathy between people living in distant lands. By presenting free trade as a form of mutual help, free traders asserted its compatibility with Christianity. Protectionists, on the other hand, compared the presumed weakening of the state’s control over the domestic market to the dissolution of order and discipline in the family. Further, they asserted that the Corn Laws ensured national self-sufficiency and claimed that the ties of affection that bound each individual to the nation would impel Britons to defend domestic producers. Public debates between proponents and opponents of the Corn Laws explored whether liberal economic practices were compatible with Christian values, patriotic attachment to the nation, and traditional gender roles.

The Corn Laws had been instated long before the nineteenth century, but it was the 1815 version that the Victorians debated and that Parliament finally repealed in 1846. Whereas in previous centuries the Corn Laws had closely regulated the exportation of grain, the act that passed on 23 March 1815 strongly restricted its importation: foreign grain could enter the British market only after the market price was at or above 80s. for wheat, 53s. for rye, peas, and beans, 40s. for barley, and 27s. for oats (Barnes 3, 139). These prices were so high that the new legislation virtually amounted to a prohibition on the importation of agricultural goods.

Before and after the passing of the 1815 Act, numerous petitioners and political economists addressed the state’s effort to protect British producers. While the landed interest sought to maintain wartime rents and prices after the Napoleonic Wars, the industrial middle class wanted lower prices. In this time of turmoil, political economists aimed to predict the future effects of the Corn Laws. In response to Thomas Malthus’s The Grounds of an Opinion on the Policy of Restricting the Importation of Foreign Corn (1815), David Ricardo published An Essay on the Influence of a low Price of Corn on the Profits of Stock: showing the Inexpediency of Restrictions on Importation (1815), arguing that all classes except the landlords would benefit from a free trade in agricultural goods.

Public discontent with the 1815 Corn Laws grew in the following decades. To alleviate concerns over the price of grain, Parliament modified the legislation a number of times, with the most significant change taking place in 1828 with the introduction of a sliding scale. William Huskisson, President of the Board of Trade, and the Duke of Wellington, Prime Minister, agreed to allow the importation of grain even before the prices reached extraordinarily high rates; however, the new law imposed significant import taxes, which would be adjusted for price levels (Schonhardt-Bailey xiv). For free trade advocates, the 1828 Act was far from satisfactory in that it failed to reverse the preference for domestic grain. As long as high import taxes were in place, the state was still protecting the landed interest.

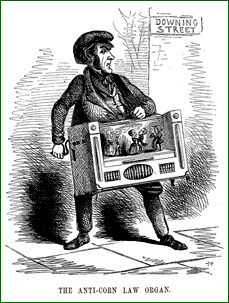

The commercial and industrial interests’ dissatisfaction with the Corn Laws led to the establishment of the Anti-Corn Law League, “the first modern and national-level political pressure group to emerge in Great Britain” (Schonhardt-Bailey xv). A group of manufacturers and merchants, including John Bright, Richard Cobden, George Wilson, and Thomas Potter, founded the organization in ![]() Manchester in 1838. Seeking to abolish the Corn Laws, the League embraced free trade as an economic system that would benefit working and middle classes at once. As Norman McCord notes, “However much they might stress the limited aims of their agitation, the Leaguers were perfectly aware that they were striking at the political and social control of the aristocracy” (Anti-Corn Law 23). The League sought to enlist industrial operatives and agricultural laborers in the cause, but managed to secure only limited support, despite the numerous operatives’ associations it established between 1839 and 1843 (Pickering and Tyrell 144). The “widespread perception of the League as an employers’ pressure group” undermined the League’s efforts to attract the masses (Pickering and Tyrell 141), and agricultural and industrial laborers alike feared that free trade would result in decreased wages (Trentmann 8; Pickering and Tyrell 142).

Manchester in 1838. Seeking to abolish the Corn Laws, the League embraced free trade as an economic system that would benefit working and middle classes at once. As Norman McCord notes, “However much they might stress the limited aims of their agitation, the Leaguers were perfectly aware that they were striking at the political and social control of the aristocracy” (Anti-Corn Law 23). The League sought to enlist industrial operatives and agricultural laborers in the cause, but managed to secure only limited support, despite the numerous operatives’ associations it established between 1839 and 1843 (Pickering and Tyrell 144). The “widespread perception of the League as an employers’ pressure group” undermined the League’s efforts to attract the masses (Pickering and Tyrell 141), and agricultural and industrial laborers alike feared that free trade would result in decreased wages (Trentmann 8; Pickering and Tyrell 142).

In trying to appeal to the working-class, the Anti-Corn Law League highlighted that free trade would serve the interests of both laborers and the employers at once. For example, Anti-Bread Tax Tracts for the People, published by the League in 1841, invited “working men” to put aside their prejudice against their employers simply because it was in their best interest to do so: “You are told that the masters are tyrants! Is that any reason why you should pay 9d. tax on every dozen of flour you and your families eat? . . . You are told to keep aloof from the anti-corn-law ‘humbugs!’ Your pockets cannot keep aloof” (132). Calling for a strategic alliance, the tract suggests that the question of whether free traders are likeable from the working-class perspective is immaterial if laborers would benefit from the repeal of the “bread-tax.” Displaying the well-known hostility between the Anti-Corn Law League and the Chartists, the tract points toward Chartist activity as the cause of the working-class mistrust of the League: “You are told to get the Charter first” (133). Seeking to mobilize emotions, many of the League’s publications employed an inflammatory rhetoric that complemented the scientific tone adopted by political economic defenses of free trade.

Many opponents of the Corn Laws seamlessly interweaved economic rhetoric with moral discourses and sentimental appeal to denounce the ills of protectionism. The so-called Corn-Law rhymer, Ebenezer Elliott, drew attention to the Corn Laws’ violation of Christian values even as he employed prose full of economic terminology. Dedicating The Corn Law Rhymes (1831) to Jeremy Bentham out of a commitment to utilitarianism, Elliott confidently discussed topics such as supply and demand, wage levels, and the exchange of manufactured goods in the introduction to the volume. His poems, in which sentimental imagery replaced the introduction’s highly specialized economic language, suggested that protectionism violates God’s order. In “Song,” one of the many poems in the volume written in the form of devotional songs, heaven offers refuge from the Corn Laws:

Where the poor cease to pay,

Go, lov’d one, and rest!

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

No toil in despair,

No tyrant, no slave,

No bread-tax is there,

With a maw like the grave. (1-2, 9-12)

Featuring impoverishment and starvation as persistent themes, Elliott’s poetry appealed to the working class, which accounts for the Anti-Corn Law League’s relative success in enlisting the people in the free trade cause in ![]() Sheffield, Elliott’s hometown, in the late 1830s (Pickering and Tyrrell 147).

Sheffield, Elliott’s hometown, in the late 1830s (Pickering and Tyrrell 147).

The principle of mutual help surfaced frequently in the League’s publications. Through trade, one nation could supply what another lacked. As Cobden put it, “Free Trade, in the widest definition of the term, means only the division of labor, by which the productive powers of the whole earth are brought into mutual cooperation” (17). According to this principle, just as the interests of middle and working classes coincided, so did those of nations when it came to free trade. Cobden and many others welcomed commerce between nations as the harbinger of world peace and believed that free trade would cultivate a sense of belonging to the worldwide community of human beings. Prohibitions on importation, they claimed, impeded the burgeoning of cooperative ties between peoples in distant lands.

If cooperation was one keyword in the public debate over the Corn Laws, dependence was another. While opponents of the Corn Laws frequently asserted that foreign trade would engender cosmopolitan sentiment, those who defended them emphasized the value of national self-sufficiency. In a diatribe against the Anti-Corn Law League, an enthusiastic protectionist hailed his nation for instating the Corn Laws: Britons, he declared, “[saw] in a strong light, the palpable fatuity of placing themselves in the humiliating position, of depending on the good will of foreigners for the supply of some of their urgent wants” (Britannicus 6). Claiming that free traders “would render [Britons] entirely dependent on foreigners for [their] daily bread,” he urged them instead to recognize that the middle class was “wholly dependent on the Landed-Interest” (Britannicus 25).

In addition to praising national self-sufficiency, supporters of the Corn Laws appealed to ideals of domesticity and femininity to defend the preference for domestic produce. To stress the paternalist principle that the landed interest willingly took care of the poor, propaganda by protectionists often conjured up a parental figure. For example, an allegory published under the pseudonym Solon, titled “The Old Sow and Her Litter of Pigs,” employed the figure of a devoted mother to demonstrate how the Corn Laws benefit the masses. In this tale, at first the piglets live happily, thriving on their mother’s milk, but then one rebellious youngster claims that their mother has established a monopoly on acorns. He tells the others that they have as much a right to acorns as their mother. “[D]etermined to maintain the rights of pigs, equality, and free trade,” the piglets start collecting acorns when their mother is asleep (1). Deprived of food, the emaciated mother can no longer suckle her babies, who end up starving to death along with her. The rebellious youngsters fail to understand how the mechanism of production works because they cannot recognize maternal benevolence. The allegory seeks to redeem economic protectionism by reaffirming traditional notions of feminine altruism. From the protectionist perspective, to call the government’s restriction of importation into question was to challenge the traditional family structure (Çelikkol 101-2).

For both free traders and protectionists, the repeal of the Corn Laws concerned not only the price of bread, but also domestic harmony, religious faith, and neighborly cooperation. The repeal in 1846 resulted from debates whose scope went far beyond wages and sustenance, but responded most directly to the famine in ![]() Ireland, where the potato crop had failed. The situation led the conservative Prime Minister Robert Peel to ask his cabinet to admit all foods without import duties, even though this motion in itself did not resolve the crisis in Ireland—the availability of food did not mean peasants could buy it. To the chagrin of many in his own party, Peel called for a “total and absolute repeal for ever of all duties on articles of subsistence” (Peel 121). Indeed, Peel may have begun to entertain free trade principles long before 1846; the support that Peel showed for William Huskisson’s commercial reforms when he was a minister in Lord Liverpool’s government in the 1820s arguably reveals an earlier interest in free trade (Jenkins 124-25). On 16 May 1846, members of parliament passed Peel’s bill to repeal the Corn Laws, and the repeal was approved by the House of Lords on 25 June 1846. Conservatives criticized Peel for betraying his own party, and he resigned as Prime Minister on 29 June 1846.

Ireland, where the potato crop had failed. The situation led the conservative Prime Minister Robert Peel to ask his cabinet to admit all foods without import duties, even though this motion in itself did not resolve the crisis in Ireland—the availability of food did not mean peasants could buy it. To the chagrin of many in his own party, Peel called for a “total and absolute repeal for ever of all duties on articles of subsistence” (Peel 121). Indeed, Peel may have begun to entertain free trade principles long before 1846; the support that Peel showed for William Huskisson’s commercial reforms when he was a minister in Lord Liverpool’s government in the 1820s arguably reveals an earlier interest in free trade (Jenkins 124-25). On 16 May 1846, members of parliament passed Peel’s bill to repeal the Corn Laws, and the repeal was approved by the House of Lords on 25 June 1846. Conservatives criticized Peel for betraying his own party, and he resigned as Prime Minister on 29 June 1846.

The Manchester school of liberal thought embraced the repeal as an emblem of the triumph of free trade over protectionism, and of the middle class over the landed interest, but such attempts to assign symbolic significance obscures the complexity of actual historical developments. Indeed, before the repeal, there had been many landowners who questioned whether the Corn Laws of 1815 served their best interest, and vociferously opposed the legislation (Wordie 51). Just as reactions to the Corn Laws did not always follow class lines, the transition to free trade was far from absolute. After 1846, protectionist legislation such as the Navigation Laws remained in place, and so-called free trade practices continued to coexist with protectionist practices—especially imperial preferences—that the Anti-Corn Law League leaders and other liberals had opposed before the repeal.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published January 2012

Çelikkol, Ayşe. “On the Repeal of the Corn Laws, 1846.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Barnes, Donald Grove. A History of the English Corn Laws from 1660-1846. New York: Augustus Kelley, 1961. Print.

Britannicus. Corn Laws Defended; Agriculture our First Interest, and the Mainstay of Trade and Commerce. Leeds: T. Harrison, [1844]. Print.

Çelikkol, Ayşe. Romances of Free Trade: British Literature, Laissez-Faire, and the Global Nineteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press: 2011. Print.

Cobden, Richard. Letter to Henry Asworth. 10 April 1862. The Political Writings of Richard Cobden. Vol 2. London, William Ridgway, 1868. 5-21. Google Book Search. Web. 22 Dec. 2011.

Eliot, George. Felix Holt: The Radical. New York: Penguin Books, 1995. Print.

Elliott, Ebenezer. “Song.” The Splendid Village; Corn Law Rhymes, and Other Poems. London: Benjamin Steill, 1834. Google Book Search. Web. 22 Dec. 2011.

Jenkins, T. A.. Sir Robert Peel. New York: St. Martin’s, 1999. Print.

Manchester Anti-Corn Law Association. Anti-Bread-Tax Tracts for the People, no. 3. 1841. Free Trade: The Repeal of the Corn Laws. Ed. Cheryl Schonhardt-Bailey. Bristol: Thoemmes, 1996. Print.

McCord, Norman. The Anti Corn-Law League 1838-1846. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd, 1958. Print.

—. Free Trade: Theory and Practice from Adam Smith to Keynes. Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1970. Print.

Peel, Robert. Letter to Heytesbury. 15 October 1845. Memoirs by the Right Honourable Sir Robert Peel. London: John Murray, 1857. 121-23. Google Book Search. Web. 22 Dec. 2011.

Pickering, Paul A. and Alex Tyrell. The People’s Bread: A History of the Anti-Corn Law League. London: Leicester UP, 2000. Print.

Schonhardt-Bailey, Cheryl, Ed.. Introduction. Free Trade: The Repeal of the Corn Laws. Bristol: Thoemmes, 1996. Print.

Solon. Corn-Law Prose: Containing the Old Sow and her Little Pigs: Look Before You Leap: and a Letter to the Author of “Thoughts on the Corn-Laws.” Sheffield: Whittaker and Co., 1834. Print.

Trentmann, Frank. Free Trade Nation: Commerce, Consumption, and Civil Society in Modern Britain. New York: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Winch, Donald. “Between Feudalists and the Communists: Louis Mallet and the Cobden Creed.” Rethinking Nineteenth-Century Liberalism: Richard Cobden Bicentenary Essays. Eds. Anthony Howe and Simon Morgan. Burlington: Ashgate, 2006. Print.

Wordie, J. R. “Perception and Reality: the Effects of the Corn Laws and their Repeal in England, 1815-1906.” Agriculture and Politics in England, 1815-1939. Ed. J. R. Wordie. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000. Print.