Abstract

This essay surveys representations of the first Anglo-Afghan campaign (1839-42) in an effort to recast the narrative of the war so that it accounts for the variety of native actors in the war and in the geopolitical crises leading up to it. The “Great Game” may have been a “tournament of shadows” between the British and the Russians, but it was entangled by both local dynastic conflicts and a challenging, even insurgent, physical terrain as well. Though the British officially won the war, Afghanistan was hardly secure either during the occupation or in the decades that followed. In that sense, the first Anglo-Afghan war presaged a century of precarious imperial power on the frontier of the Raj.

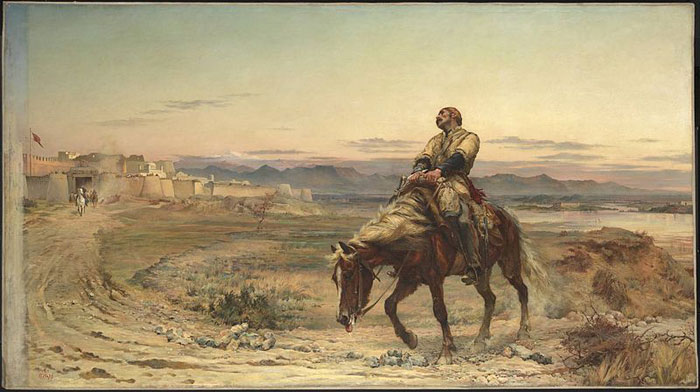

One of the most arresting British images of the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-1842) is Lady Elizabeth Butler’s painting, Remnants of an Army (1874). (See Figure 1.) It shows William Brydon, an assistant surgeon in the East India Company, astride a bedraggled horse limping across an otherwise deserted plain. Brydon was one of the sole survivors of a force of 4,500 strong that was routed from

Despite the legend that Lady Butler’s painting helped to promote, Brydon was not the sole British survivor of the Kabul rout. Several dozen others were captured, among them Lady Florentia Sale, wife of Major General Sir Robert Sale, who commanded the garrison at Jalalabad. Lady Sale, for her part, survived her nine months’ captivity; wrote an account of her experiences, A Journal of the Disasters in Afghanistan, 1841-42; and was widely admired for her acts of bravery during her imprisonment.[1] But despite individual acts of heroism, the retreat from Kabul, and the subsequent massacre, came to be symbols not just of a single military disaster but also of a precarious imperial strategy that engendered that subject of interregional conflict and far-reaching geopolitical crisis known as the “Great Game.” Attributed to Arthur Conolly (an East India Company captain and intelligence officer), the term refers to the contest between Britain and ![]() Russia over which imperial hegemon would dominate Central Asia in the nineteenth century. In fact, British and Russian designs in the late 1830s were part of a multi-sited struggle between would-be global powers on the one hand and native forces on the other—including the once formidable Sikh empire and a complex of regional tribesmen seeking dominion, if not sovereignty, in this “graveyard of empires.”

Russia over which imperial hegemon would dominate Central Asia in the nineteenth century. In fact, British and Russian designs in the late 1830s were part of a multi-sited struggle between would-be global powers on the one hand and native forces on the other—including the once formidable Sikh empire and a complex of regional tribesmen seeking dominion, if not sovereignty, in this “graveyard of empires.”

The British feared Russia’s ambition along the northwest frontier, which was viewed by both parties as the gateway to ![]() India. But they were also wary of the Persians, who, in 1834, had their eye on

India. But they were also wary of the Persians, who, in 1834, had their eye on ![]() Herat—one of a number of strongholds they had lost in the wake of the collapse of the Safavid dynasty in the second half of the eighteenth century and had been striving to recover ever since (Ewans 21). In that sense, the “Great Game” involved more than two players; in fact it had many dimensions, only some of which depended on the mutual suspicions of two European powers. Though later historians have famously viewed the war as a “tournament of shadows” between two western powers with locals as proxies, Victorians representing the war exhibited more respect, albeit often grudging, for the power, impact, and historical significance of regional dynastic regimes, even as they often relished seeing them caught in the crosshairs of a wider global-imperial struggle for hegemony.[2]

Herat—one of a number of strongholds they had lost in the wake of the collapse of the Safavid dynasty in the second half of the eighteenth century and had been striving to recover ever since (Ewans 21). In that sense, the “Great Game” involved more than two players; in fact it had many dimensions, only some of which depended on the mutual suspicions of two European powers. Though later historians have famously viewed the war as a “tournament of shadows” between two western powers with locals as proxies, Victorians representing the war exhibited more respect, albeit often grudging, for the power, impact, and historical significance of regional dynastic regimes, even as they often relished seeing them caught in the crosshairs of a wider global-imperial struggle for hegemony.[2]

The key to British stability on this fraught frontier was thought to be the Emir of Afghanistan, Dost Mohammed, scion of the Barakzai tribe and a man at the very intersection of several imperial gambols. Though he was courted by the British and sought alliance with the Russians, it was the empire of the Sikhs and more particularly its seasoned leader, Ranjit Singh, who was his longstanding nemesis. Singh, the first Sikh Maharaja, was at the end of his life when these tensions flared, but he was a formidable warrior almost until the last (a series of strokes beset him in 1837 from which he was unable to recover). Singh had been engaged in conflict with the Afghans for the better part of 20 years and specifically with the Barakzais, whom he defeated in 1834. His forces fought Dost Mohammed again in 1837, and that victory allowed him to retake ![]() Peshawar, thereby consolidating the Sikh Raj and capping his career as the so-called lion of the Punjab.

Peshawar, thereby consolidating the Sikh Raj and capping his career as the so-called lion of the Punjab.

So while the British sought in Dost Mohammed a bulwark against Russian imperial ambition, the Great Game was arguably a side-show to local imperial-dynastic contests in which he and his family had been entrenched for decades. Though he had pledged fealty to the British, his relationship with the Russians was a cause for concern; once he was perceived as a double-crosser, his reputation in British imperial history as a duplicitous warlord was sealed and only negligibly revised by the fact that he was again an ally after the end of the war. This is not to say that the British did not try to play him against Singh or against the Russians. They were attuned to the regional stakes of their diplomatic mission and divided on the prospect of an alliance with Dost Mohammed: Lord Auckland, the Governor General, was less well disposed toward him than his political agent on the ground, Sir Alexander Burnes. Neither of them was capable of fully appreciating the fact that their quest to bind Dost Mohammed fully to them was not to be. For his main concern was Company support against the Sikhs in the recapture of Peshawar, which the British were unprepared to offer (Schofield 65). Auckland’s “Simla Manifesto” of 1838—which stated that the British needed a reliable ally on the northwestern frontier in order to secure India—was not exactly a declaration of war, though it was a pretext for intervention. Failing Dost Mohammed’s cooperation, in March of 1839 Sir Willoughby Cotton advanced through the Bolan Pass![]() , installed Shah Shuja as the new emir, and occupied Kabul. Dost Mohammed obtained a fatwa and declared jihad, but the local histories of Barakzai aggression meant that his natural base in southern Afghanistan was loathe to support him. He fled, later gave himself up after attempting a failed insurrection, and ended up in exile in India (Lowen and McMichael 19).

, installed Shah Shuja as the new emir, and occupied Kabul. Dost Mohammed obtained a fatwa and declared jihad, but the local histories of Barakzai aggression meant that his natural base in southern Afghanistan was loathe to support him. He fled, later gave himself up after attempting a failed insurrection, and ended up in exile in India (Lowen and McMichael 19).

Shah Shuja had long been tethered to the British, not as ally so much as supplicant: he had been overthrown by a rival in 1809 and had been living in exile in India ever since. The singular advantage he had over Dost Mohammed was that he was an ally of both the British and the Sikhs, with whom he had actually brokered a treaty in 1833. The British determined, in other words, that embracing an enemy of the Sikhs was worse for the security of India than supporting their nominal ally.[3] Though the march to Kabul was by no means easy, though the countryside was not subdued until well into 1841 (if ever), and though local tribesmen and peasants continued to attack supplies and convoys on a regular basis, the fortress of Ghanzi fell relatively quickly in summer of 1839. And though today’s historians may assess that particular conquest as self-evident, eyewitness accounts testify to the stop-and-start character of the struggle on the ground and the lack of finality, if not of victory, that characterized the whole campaign for Afghanistan in this period. Meanwhile, the occupation of Kabul—undertaken to stabilize Shah Shuja’s early reign—dragged on for three years, looking increasingly permanent to a variety of observers, Afghan residents prime among them.

In part to palliate officers and soldiers, military officials encouraged families to join the occupying army in the city. Life under the occupation was routinized and pleasant, at least for some: Lady Sale had an elaborate kitchen-garden attached to her house where she grew sweet peas, geraniums, potatoes, cauliflowers, radishes, turnips, artichokes, and lettuce. Though she professed the Kabul variety of the latter “hairy and inferior to those cultivated by us,” she found the Kabul cabbages “superior, being milder,” and remarked on how well the red cabbage grown from English seed did even in the bracing climate of Afghanistan (Sale 29). Others were more restless. Afghans were particularly discomfited by the traffic in native women that moved in and out of the cantonments. As one historian has noted, “the proverb ‘necessity is the mother of invention and the father of the Eurasian’ was manifest” (Schofield 71). The cost of maintaining such a large military and civilian contingent was a drain on the Indian treasury; the danger to supplies and to the occupiers themselves at all ranks was considerable and, in some cases, fatal. Burnes was assassinated in the context of an uprising directed at least in part against the occupation forces: he was hacked to death by a mob despite trying to reason with them, it is said, in his best Persian (Schofield 72). The revolt spread; the Afghans were bombarding the cantonment, and it was clear that the security of Kabul was in peril. Sir William Macnaghten, advisor to Auckland, was forced to negotiate with the new Afghan leader, Akbar Khan, son of Dost Mohammed. The terms were humiliating—total withdrawal, safe passage, and the return of Dost Mohammed as emir—but Macnaghten was confident they would be met. Instead, Akbar Khan ambushed him and his three assistants. Macnaghten’s body was dragged through the streets of Kabul and his head paraded as Akbar’s prize: symbols of British defeat and humiliation and a harbinger of worse to come.

The retreat and the massacre that followed were among the bloodiest episodes in British imperial history. One witness estimated that 3,000 men and women alone died on 7 January 1842. As they did, they could look back and see “the glow of the fire that now consumed their cantonment” (Norris 379). Sir William Elphinstone and several other officers were taken prisoner by Akbar Khan, which added to the demoralization and sheer despair in situ. Any resistance that British troops were inclined to put up, either as a fighting force or as a human collectivity, was significantly hampered by the notorious mountain gorges and by the bitter cold and snow, which survivors described in vivid terms as red with the blood of men, women, and children, not to mention camels and horses as well. The destruction of the retreating army—what the late-nineteenth-century historian Archibald Forbes called “the shock of the catastrophe in the passes” —galvanized Auckland, who authorized Field Marshall Sir George Pollock to organize an “army of retribution, even though this had not been part of the original plan” (Forbes 135; Clements 204). Kabul was retaken by the fall of 1842 and its bazaar destroyed by British forces in retaliation; the British hostages were released via negotiations that granted their guardian, Sahel Muhammed, a pension for life. Akbar Khan was finally defeated, though his father—whose political activities had not been diminished by exile—quickly reestablished his authority in Afghanistan, where he continued to shape the fortunes of Central Asia, mostly in alliance with the British, until his death in 1863.

Despite his “relative powerlessness” during the early years of his reign, Dost Mohammed shaped Victorian Afghanistan as much as if not more than the British (Noelle 36). He may be seen as part of a long line of patrimonial state-builders: a prime example of the “empire of tribes” at the heart of Afghan state formation and one of the region’s three “giant players” in the Victorian period (Misdag 48-9; Kakar 1).[4] As significant for the region’s history was the death of Ranjit Singh in 1839, which left his kingdom vulnerable and drew his successors into several wars with the East India Company in the later 1840s. The annexation of the Punjab was the result. Following so closely on the heels of the debacle in Afghanistan, these post-war events demonstrate how inextricably linked the empires of tribes were with each other, with the fate of the Great Game, and of course with the conflagration yet to come: the Mutiny of 1857. Significantly, Dost Mohammed kept his alliance with the British in that fight even though his aid to the rebels might have tipped the balance.

If these imperial histories are tightly woven, their interstitial connections have not come to the fore in historiographies of the first Anglo-Afghan war, at least not in any sustained way. Indeed, only very recently have western scholars tried to conceive of this region, punctuated by multiple spheres of influence and ambition, as having its own autonomous histories of “frontier governmentality,” however fragmented it was.[5] Ironically, late twentieth and early twenty-first-century wars in the region have made such histories all the more necessary, even as they have spawned an outpouring of Great Game-ish accounts. From the nineteenth century onward, then, historians have more typically than not linked the first war with the second (1878-80) and have wrestled chiefly with the question of blame for the former. Archibald Forbes, in his 1896 account of both the first and second wars, takes issue with Sir John Kaye’s view that the British had done all they could in the face of Dost Mohammed’s betrayal by installing Shah Shuja. He then goes after Auckland, as have numerous historians before and since, many of whom open their narrative with reference to that common Victorian sobriquet for the war “Auckland’s folly” (Forbes 32). Afzal Iqbal, writing under the imprimatur of the Research Society of Pakistan in the 1970s, concurred with these indictments and even sought to rehabilitate the ill-fated Burnes in the process.

Punjabi scholars have had a lot to say about the role of Mohan Lal, who was engaged by Burnes as a commercial agent because of the Persian language skills he had acquired in ![]() Delhi. Lal’s writings remain a major source for how events unfolded especially during the insurrection at Kabul in 1841; he was also at least indirectly involved in the assassination of Mir Masjidi, an Afghan chief who was a sworn enemy of the British (Gupta 245-6).[6] The role of the sepoys, Indian soldiers who fought in the British army (from the Persian sipahi), has also been extensively noted by both witnesses to and historians of the campaign. Their bravery and their martial skills come across vividly in a variety of accounts and in some of the paintings of the war as well. James Atkinson, superintending surgeon to the Army of the Indus, not only wrote of his experiences but produced images of them as well, including a watercolor view of Sepoys Attacking Baluchi Snipers in the Siri-Kajur Pass (1839).[7] Though they may not have had as intimate a knowledge of the local terrain as the Khyberees and Baluchis sniping at them, by all accounts the sepoys were more adept at maneuvering in the rough terrain than the average British soldier.

Delhi. Lal’s writings remain a major source for how events unfolded especially during the insurrection at Kabul in 1841; he was also at least indirectly involved in the assassination of Mir Masjidi, an Afghan chief who was a sworn enemy of the British (Gupta 245-6).[6] The role of the sepoys, Indian soldiers who fought in the British army (from the Persian sipahi), has also been extensively noted by both witnesses to and historians of the campaign. Their bravery and their martial skills come across vividly in a variety of accounts and in some of the paintings of the war as well. James Atkinson, superintending surgeon to the Army of the Indus, not only wrote of his experiences but produced images of them as well, including a watercolor view of Sepoys Attacking Baluchi Snipers in the Siri-Kajur Pass (1839).[7] Though they may not have had as intimate a knowledge of the local terrain as the Khyberees and Baluchis sniping at them, by all accounts the sepoys were more adept at maneuvering in the rough terrain than the average British soldier.

Visual and textual images of the monstrous gorges and formidable mountain defiles are most commonly referenced in the context of the terrible flight from Kabul. But in fact memoirs of the war are filled with descriptions of both the harsh landscape and its lush fruits and captivating vistas as well. Officers like Henry Havelock and James Atkinson, both of whom chronicled the war only up to 1840, were repeatedly taken by sights like the “picturesque ravine, fringed with high reeds and groves of the jujube and the neem tree” or the “sweet silver line of river” that might erupt in the most unexpected places (Havelock 1: 202; Atkinson 184). At times their narratives read like naturalists’ accounts, if not environmental histories as well. In that sense, those who chronicled the first Afghan war fell in behind a long tradition of ethnographic writing about the region: from Elphinstone’s 1815 two-volume An Account of the Kingdom of Cabul onward, the British viewed knowledge about local flora and fauna as military intelligence despite the fact that it appeared to do them little good in the actual field. And because the war itself was only intermittently “battle-centric,” the British were perpetually bracing against the possibility of sudden skirmishes and sniping (Roy 6).[8] These were the kinds of guerrilla tactics that would keep them on the defensive along the northwest frontier at least until the end of the century, when Winston Churchill wrote about the Malakand field forces as a war correspondent and recorded similarly failed and fitful British military responses to by now well-practiced anti-colonial tribal warfare.[9] Significantly, while narratives of the first Anglo-Afghan war have their share of orientalist tropes—representing Afghans and tribesmen as savage, deceitful, and terrifying opponents—such rhetoric was arguably more common in and around the second war (1878-1880), as was the British preoccupation with jihad and “fanaticism.” Nonetheless, Victorian representations from and about the 1839-42 war conveyed a sense of the ongoing challenges to imperial security and stability that Afghans, and Afghanistan, routinely posed, both in and outside of battle per se. Though Afghanistan was technically held by the British until the third Afghan war in 1919, through which an independent Afghan nation was created, British hegemony there remained precarious and vulnerable across the whole of the nineteenth century.

The first Anglo-Afghan war has had a long life in the British imperial imagination. Even as the second Anglo-Afghan war was breaking out, historians were busy producing histories of its predecessor and predicting future failures.[10] In his 1902 novel, To Herat and Cabul, G.A. Henty prefaced his fictional account of the first Afghan campaign with the observation that “in the military history of this country there is no darker page than the destruction of a considerable British force in the terrible defiles between Cabul and Jellalabad in January, 1842” (v). In the pages that follow, he gives one of the most concise, and jingoistic, accounts of the main events of the war, dramatizing them for a generation of readers who were hungry for imperial fiction, especially of the boys’ adventure kind for which he was so well known. Fiction writers have been fascinated for decades by the spectacular failure of this first campaign. Treatments include Maud Diver’s 1913 Judgment of the Sword, which focuses on Herat, and George MacDonald Fraser’s best-selling 1969 Flashman novel (the first of a series). The latter has been the most popular vehicle for bringing the first Anglo-Afghan war to 20th-century readers. Larger than life, Harry Paget Flashman is the protagonist at Gandamak, Jalalabad and Kabul, imprinting generations of imperial adventure fans with images of British derring-do. Meanwhile, Patrick Hennessey’s 2009 The Junior Officers’ Reading Club, subtitled Killing Time and Fighting Wars and dedicated to memorializing his own Afghan tour (among others), is the most recent echo of the bravado and nervy self-confidence of English men “growing up in today’s messy small wars,” as the back cover blurb enthusiastically—and all-too blithely—proclaims.

How twenty-first-century writers will take up the first Afghan war as they seek to make connections and disconnections with contemporary events remains an open question, though the chain of narratives has already begun.[11] The real challenge for historians seeking to write anti-imperial histories will be to break free of the dichotomous great game story and re-materialize Afghans and other “natives” as agents, right-sizing their role in shaping the character of the war and its outcomes. What’s needed, in other words, is a truly postcolonial history of the first Anglo-Afghan war—one which tries to recapture the seeds of that narrative that are everywhere to be found in the Victorian representations of it, should we care to seek them.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

published August 2012

Burton, Antoinette. “On the First Anglo-Afghan War, 1839-42: Spectacle of Disaster.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Atkinson, James. The Expedition into Affghanistan: Notes and Sketches Descriptive of the Country, Contained in a Personal Narrative During the Campaign of 1839 and 1840. London: William Allen, 1842. Print.

Bean, Richard et al. The Great Game: Afghanistan. London: Oberon Books, 2010. Print.

Churchill, Winston. The Story of the Malakand Field Force. 1898. London: Leo Cooper, 1989. Print.

Clements, Frank A. Conflict in Afghanistan: A Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC CLIO, 2003. Print.

Durand, Sir Henry Marion. The First Afghan War and Its Causes. London: Longman’s Green, 1879. Print.

Elphinstone, Montstuart. An Account of the Kingdom of Cabul and Its Dependencies in Persia, Tartary, and India. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1815. Print.

Ewans, Martin. Conflict in Afghanistan: Studies in Asymmetric Warfare. New York: Routledge, 2005. Print.

Forbes, Archibald. The Afghan Wars, 1839-1882 and 1878-80. London: Seeley and Co., 1896. Print.

Fraser, George MacDonald. Flashman; from the Flashman Papers 1839-1842. New York: World Publishers, 1969. Print.

Gupta, Hari Ram. Panjab, Central Asia, and the First Afghan War. Chandigarh: Panjab University, 1940. Print.

Havelock, Henry. Narrative of the War in Affghanistan in 1838-39. Vol. 1. London: Henry Colburn Publishers, 1840. Print.

Hennessey, Patrick. The Junior Officers’ Reading Club: Killing Time and Fighting Wars. London: Penguin, 2009. Print.

Henty, G.A. To Herat and Cabul: A Story of the First Afghan War. London: Blackie and Sons, 1902. Print.

Hopkins, Benjamin D. and Magnus Marsden. Fragments of the Afghan Frontier. New York: Columbia UP, 2011. Print.

Iqbal, Afzal. Circumstances Leading to the First Afghan War. Punjab, Lahore: Research Society of Pakistan, 1975. Print.

Kakar, M. Hassan. A Political and Diplomatic History of Afghanistan, 1863-1901. Boston: Brill, 2006. Print.

Loewen, Arley and Josette McMichael, eds. Images of Afghanistan: Exploring Afghan Culture through Art and Literature. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2010. Print.

Macrory, Patrick, ed. Lady Sale: The First Afghan War. Hamden: Archon Books, 1969. Print.

Maccrory, Patrick. Signal Catastrophe: The Story of the Disastrous Retreat from Kabul, 1842. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1966. Print.

Misdaq, Nabi. Afghanistan: Political Frailty and Foreign Interference. London: Routledge, 2006. Print.

Nehru, Jawaharlal. “Introduction.” Panjab, Central Asia, and the First Afghan War. By Hari Ram Gupta. Chandigarh: Panjab University, 1940. iii-iv. Print.

Noelle, Christine. State and Tribe in Early Afghanistan: The Reign of Amir Dost Muhammad Khan (1826-1863). Surrey, UK: Curzon, 1997. Print.

Norris, J.A. The First Afghan War, 1838-1942. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1967. Print.

Roy, Kaushik. “Introduction: Armies, Warfare and Society in Colonial India.” War and Society in Colonial India. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006. 1-52. Print.

Schofield, Victoria. Afghan Frontier: Feuding and Fighting in Central Asia. London: Tauris, 2003. Print.

Sale, Lady Florentia. Journal of the Disasters in Affghanistan, 1841-42. 1843. Lahore: Sang-E-Meel Publishers, 1985. Print.

Singh, Khuswant. Ranjit Singh: Maharajah of the Punjab, 1780-1839. London: George Allen Unwin, 1962. Print.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Zarena Aslami, “The Second Anglo-Afghan War, or The Return of the Uninvited”

ENDNOTES

[1] See Patrick Macrory, ed., Lady Sale: The First Afghan War.

[2] See, for example, Patrick Maccrory, Signal Catastrophe: The Story of the Disastrous Retreat from Kabul, 1842 19.

[3] As Fakir Azizuddin reassured Lord Auckland when he was about to meet Ranjit Singh in 1838, “the lustre of one sun (Ranjit) has long shone with splendor over our horizon; but when two suns come together, the refulgence will be overpowering” (Singh 209).

[4] Kakar names Dost Mohammed’s son, Sher Ali Khan and his grandson, AbdurRahman Khan, as the other two “giants.”

[5] See Benjamin D. Hopkins and Magnus Marsden, Fragments of the Afghan Frontier.

[6] This edition of Gupta’s Panjab, Central Asia, and the First Afghan War has an introduction by Jawaharlal Nehru, who calls Lal a “fascinating person” who “in a free India . . . would have risen to the topmost rungs of the political ladder” (iv, iii).

[7] See James Atkinson, The Expedition into Affghanistan: Notes and Sketches Descriptive of the Country, Contained in a Personal Narrative During the Campaign of 1839 and 1840. For the watercolor see http://www.europeana.eu/portal/record/92037/D1CD9875D70D9C904A2079F2D43FAFF6FD828BB3.html

[8] Also see Montstuart Elphinstone’s An Account of the Kingdom of Cabul and its Dependencies in Persia, Tartary, and India.

[9] See Winston Churchill’s The Story of the Malakand Field Force.

[10] For example, see Sir Henry Marion Durand’s The First Afghan War and its Causes.

[11] See Richard Bean et al., The Great Game: Afghanistan.