Abstract

The series of annual international exhibitions held during the early 1870s at South Kensington, London, were not particularly successful, or popular, but they were influential in the history of exhibitions. The alleged failures and the cancellation of the final annual exhibition halfway through the intended decade-long series of events provoked considerable discussion about the purpose, scale and expectations for exhibitions, which were no longer novel or limited to a particular city or nation-state. There were some successes, notably for the Australian colonies and British India, and for very specific trades and exhibitors, but the public discussion and those limited successes have generally failed to capture the attention of scholars. These events are rarely mentioned in books and articles about exhibitions and, when discussed, are considered to be failures without merit. This BRANCH contribution recognizes that other exhibitions were more popular and more successful, but also recognizes that the South Kensington shows were significant in addressing criticisms of exhibitions in general and in the generational history of both the shows and their organizers. The 1870s proved to be a pivotal period in the history of such exhibitions and the consideration of what merited public culture. The mantle was passed from Sir Henry Cole to his successors and the ambition of holding annual international exhibitions was replaced by more thematic shows in Britain and bold international shows in the Australian colonies. Amidst the general impressions of failure, there were also successes at the shows and those highlighted how inter-national exhibitions could prove useful in a changing world.

Introduction

International exhibitions were hardly new or rare as the decade of the 1870s began. In Britain alone, major exhibitions had been held in London, Manchester, and Dublin, among other cities, and the mania spread across the seas to ![]() France, the United States and British colonies in South Asia and Australasia. In one way or another, those popular events combined the appeals of fairs, museums, art galleries and stores. One might even add public gardens to that list. Millions of visitors enjoyed, observed and consumed a galaxy of commercial goods, works of art, scientific samples and machines, not without opposition and dissent, but also not without a general consensus that the temporary international exhibition was worth its many costs and challenges. That consensus no longer held as Sir Henry Cole (1808-1882) initiated and subsequently prematurely terminated his scheme of ten annual international exhibitions at South Kensington, London. By the end of 1874, the Executive Commissioner had abandoned his bold plans in the face of declining and eventually untenable attendance, reluctance on the part of significant exhibitors to participate, or to return the following year to participate again, and the relatively little positive attention paid to the shows in the press. There was, though, a loud and constant chorus of private and public criticism about what Cole himself termed, “imperfect experiments” (“A Special Report” xxxvii).

France, the United States and British colonies in South Asia and Australasia. In one way or another, those popular events combined the appeals of fairs, museums, art galleries and stores. One might even add public gardens to that list. Millions of visitors enjoyed, observed and consumed a galaxy of commercial goods, works of art, scientific samples and machines, not without opposition and dissent, but also not without a general consensus that the temporary international exhibition was worth its many costs and challenges. That consensus no longer held as Sir Henry Cole (1808-1882) initiated and subsequently prematurely terminated his scheme of ten annual international exhibitions at South Kensington, London. By the end of 1874, the Executive Commissioner had abandoned his bold plans in the face of declining and eventually untenable attendance, reluctance on the part of significant exhibitors to participate, or to return the following year to participate again, and the relatively little positive attention paid to the shows in the press. There was, though, a loud and constant chorus of private and public criticism about what Cole himself termed, “imperfect experiments” (“A Special Report” xxxvii).

This essay will consider what changes in exhibitions Cole proposed and why he did so—his “experiments”—, what he and his colleagues solicited and the response to some of those exhibits, and the discussion of why his scheme failed. There is relatively little scholarship on these Annual International Exhibitions, in part because they were perceived at the time as failures. The contemporary discussion about the events and the explanations for their failure can, though, deepen our understanding of the history of exhibitions, which included significant dissent and changes, and of how exhibitions did and did not correspond to wider issues of public society and culture. Much was at stake with Cole’s innovative scheme and with the reasons given for its failure. Those two topics remained of interest in the press and among exhibition participants well into the 1880s and, by association, beyond England’s shores. The seeming failures remained of interest as organizers, exhibitors and observers continued to reflect on what type of exhibition could be most successful in a changing world.

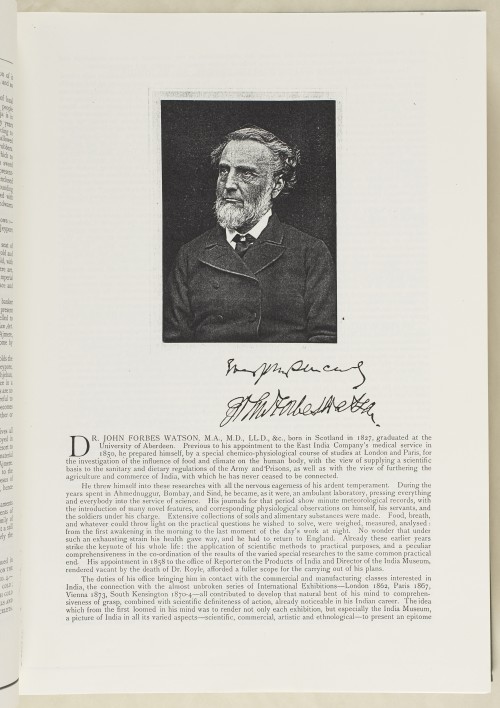

Reflection on the South Kensington shows was a reflection on Victorian society and public life, as key contemporaries understood at the time. Those included Cole, for whom the shows were a personal and professional failure, and exhibition advocates, who pondered how to match exhibitions and the public in a more mutually beneficial way. John Forbes Watson (1827-1892) and Trueman Wood (1845-1929) were among such vocal recognized figures. They were both fully engaged with exhibitions from their respective positions at the India Office and Museum, and the Royal Society of Arts. More often than not that engagement was in the form of organizing displays and membership on official committees and commissions.[1] Other participants at the time, and within a decade or so after the international exhibitions, included members of London’s trades and business communities, exhibitors and officials at colonial shows, and noteworthy British commentators on museums and other cultural institutions.

Failure at South Kensington by the end of 1874 did not mean an end to exhibitions, although Wood, among others, looking back ten years later thought that it could have. He wrote: “The failure of this scheme was thought to have put a stop to exhibitions in this country, at all events for a long time” (637). Rather, conversations were about how exhibitions had to change because the wider world was changing. Reflections on what the public wanted and how exhibitions could both respond to and shape those desires bore fruit with popular shows in the 1880s and 1890s. Those successes at ![]() South Kensington and other exhibition venues were influenced by the public discussion of Cole’s failure.

South Kensington and other exhibition venues were influenced by the public discussion of Cole’s failure.

South Kensington shows in the 1870s were fundamentally different than other exhibitions as a consequence of Cole’s professional goals and in recognition that the shock of the novel and the seduction of the global had worn off. Or, perhaps as one popular guidebook suggested, the international shows’ “very success had led to their abandonment,” as they could not keep pace as they advertised that they would with “the growth of art, science, and industry” (Yapp 1). A second guidebook suggested at the time that such exhibitions also tended to create “a very considerable disturbance of trade,” contrary to the promise of increased trade (Nelson’s 5). Those were not unusual or peripheral concerns. Nor was the growing sense that the vast array of exhibits was so overwhelming that it was impossible to have meaningful study and learning. After touring the grounds at the ![]() Paris Universal Exposition in 1855, one English visitor remarked:

Paris Universal Exposition in 1855, one English visitor remarked:

The visitor is wearied with the extent and variety of things exhibited: with the endless lumps of coal, the colossal cakes of soap, the thousands of labelled bottles filled with grain, the endless array of various ores, the blue and red agricultural implements, the colossal engines, web-like spinning machinery, and the curious models (“The Paris Universal Exhibition” 527)

Might it all be too much, or at the very least, too much for only one or two visits? Machines-in-motion remained attractive, but our visitor even found it “difficult to disentangle the wheels and cranks of one machine from those of its neighbours.”

Those were serious questions about the value and purposes of large-scale international exhibitions and the nature of the Victorian public. Had a limit been reached in this world of seemingly limitless consumption, observation, education and pleasure? If such issues and their consequences had not been fully understood by Cole and his associates as they began their annual scheme, they certainly were by the time their shows prematurely ended four years later. Those questions about the relevance and nature of exhibitions would not be decisively answered by the middle of the decade. They would also be repeated in the 1880s, as exhibitors, visitors and organizers wrestled with the apparent fact that the novelty of exhibitions had worn off, seemingly along with their utility and uniqueness.

That awareness of such challenges did not mean for Cole in the early 1870s an abandonment of international exhibitions, but rather putting in place “a system differing largely from that of its predecessors” (Nelson’s 5). That change revealed that Cole was quite conscious about the scale, organization and purposes of such shows. He might have misjudged the solutions to restore exhibitions to their previous heights of popularity and significance, but that did not mean he denied that there were problems. The cancellation of his scheme confirmed a misreading, but did not confirm that there were no major problems with international exhibitions of which Cole was not aware. Put bluntly: what were recurring exhibitions good for in the post-1851 world of mass entertainment, relatively easy travel by steam and train, and department stores offering the world to consumers?

That was a question asked at the time in Britain, ![]() Australia and British

Australia and British ![]() India, as exhibitions appeared to be declining in popularity and influence. Sydney’s leading journalist derided one of his city’s major exhibitions as “a decided failure” and concluded that “the general want of interest therein by the public, clearly prove that this has been overdone” (Twopeny 186-96). Exhibition organizers in Calcutta and Bombay faced similar and considerable criticism from a variety of groups and individuals. Thus, Cole’s nearly contemporaneous failures and the discussions about them occurred at a pivotal moment in the histories of conceptualizing the public and holding world’s fairs; the two were linked in what we have come to call, “the British World,” as the events were intended to be educational, profitable, entertaining and both a reflection of and agent for public life, or a sense of society. Such concerns did not seem to affect French international exhibitions, as one was held every ten years or so between the 1855 and the end of the century. Each successive one bore a striking similarity to its popular predecessor.

India, as exhibitions appeared to be declining in popularity and influence. Sydney’s leading journalist derided one of his city’s major exhibitions as “a decided failure” and concluded that “the general want of interest therein by the public, clearly prove that this has been overdone” (Twopeny 186-96). Exhibition organizers in Calcutta and Bombay faced similar and considerable criticism from a variety of groups and individuals. Thus, Cole’s nearly contemporaneous failures and the discussions about them occurred at a pivotal moment in the histories of conceptualizing the public and holding world’s fairs; the two were linked in what we have come to call, “the British World,” as the events were intended to be educational, profitable, entertaining and both a reflection of and agent for public life, or a sense of society. Such concerns did not seem to affect French international exhibitions, as one was held every ten years or so between the 1855 and the end of the century. Each successive one bore a striking similarity to its popular predecessor.

Sir Henry Cole and His Exhibition Scheme

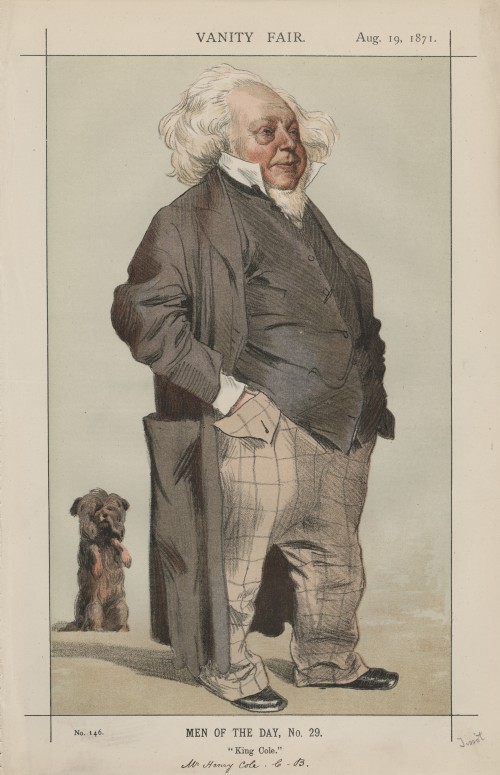

The Executive Commissioner and leading figure at the South Kensington complex had been an active exhibition enthusiast and organizer since the planning stages of the ![]() Great Exhibition. Along with Prince Albert, Cole was probably the public figure most readily associated with English exhibitions and official English participation at overseas exhibitions, including the major Paris Universal Expositions. He certainly assumed that public role after the Prince’s death in 1861. Cole’s association with exhibitions, artisan education and the South Kensington complex made him the recognized subject of serious commentaries and portraits, as well as more satirical ones. Cole was Vanity Fair’s “Men of the Day, no 29” in August 1871, amidst the first South Kensington International Exhibition. (See Fig. 1.) His dog stands on his hind legs rather obediently and subordinately. One assumes that was a reference to Cole’s employees, or a snarky reference to Cole’s alleged fawning at the feet of high-government and royal officials, a deference often linked to the Royal Society of Arts. Perhaps it held both meanings for readers? It might be added, that although Cole was rather outspoken, if not arrogant, he was hardly parochial, or jingoistic. His inclusion of overseas and non-Western art works were appreciated as potentially improving British wares and revealed a rather cosmopolitan view of art and industry.

Great Exhibition. Along with Prince Albert, Cole was probably the public figure most readily associated with English exhibitions and official English participation at overseas exhibitions, including the major Paris Universal Expositions. He certainly assumed that public role after the Prince’s death in 1861. Cole’s association with exhibitions, artisan education and the South Kensington complex made him the recognized subject of serious commentaries and portraits, as well as more satirical ones. Cole was Vanity Fair’s “Men of the Day, no 29” in August 1871, amidst the first South Kensington International Exhibition. (See Fig. 1.) His dog stands on his hind legs rather obediently and subordinately. One assumes that was a reference to Cole’s employees, or a snarky reference to Cole’s alleged fawning at the feet of high-government and royal officials, a deference often linked to the Royal Society of Arts. Perhaps it held both meanings for readers? It might be added, that although Cole was rather outspoken, if not arrogant, he was hardly parochial, or jingoistic. His inclusion of overseas and non-Western art works were appreciated as potentially improving British wares and revealed a rather cosmopolitan view of art and industry.

Figure 1: Sir Henry Cole (“Men of the Day, No. 29”), Chromolithograph by James Jacques Tissot, published in Vanity Fair 19 August 1871.

Was Cole strong-willed, even in his open-mindedness about what constituted art worth learning from? Yes. Difficult to work with? Yes. But not above learning from what he perceived were previous errors and from what others were doing. He was sincerely and keenly interested in the Paris shows of 1855 and 1867, and what might be borrowed or adapted from those French examples to improve English shows and the display of English material culture abroad. Cole most certainly held and expressed strong opinions about the utility of exhibitions and their larger cultural and moral roles. He famously contrasted exhibitions with “gin-palaces.” Exhibitions were for education first, and only for entertainment if that were subordinate to learning. They were a part of the wider Victorian ‘civilizing’ process of socialization and education. And those who could learn the most were artisans and workers, men who produced material culture in England and could improve their work by observing goods from throughout England and much of the recognized world. Models for improvement could, if not should, come from France and ![]() Spain, and also from

Spain, and also from ![]() China and India.

China and India.

None of that is intended to present a character free of controversy. In the case of Paris in 1867, Cole and his deputies were publicly criticized for many policies and actions, such as their decoration of the British galleries. That decoration “would do no credit to our common house-painter,” according to the correspondent for the Illustrated London News (“The Paris Universal Exhibition,” 247). That journalist was not finished and chastised Cole for the “cold, dull, cheerless air” of the British picture galleries, considered one of the more important British displays (257). It might be noted, though, that the weekly newspaper also praised Cole and included a portrait of the soon-to-be-former Director of the South Kensington Museum as he expressed his intention to retire in 1873 (July 12, 1873, 36 and 38).

Those criticisms and praises never seemed to deter the determined Cole. He was among those Victorians who was convinced that he knew what was right and that intransigence only grew with criticism and praise. He did, though, seek to revise exhibitions in significant ways and, in doing so, change what was exhibited and the shows’ major objectives. Such changes were also an admission that what Cole had overseen in the 1850s and 1860s had to be changed. The reforms were motivated by criticism, but perhaps even more so by his particular views about the nature and purposes of exhibitions. Cole intended to limit the displays to a few different “selected” types, or “some few classes of manufactures” each year, promote those that were innovative, or could be labeled “discoveries” and “inventions,” and emphasize the utility and quality of such objects, rather than their capacity to entertain. The shows would be “very select and limited in size” and not display those “objects obtainable in ordinary commerce and those which have been already exhibited” (“Memorandum Upon a Scheme of Annual International Exhibitions” 269).

The upcoming shows would be international in scope, but not universal, in contrast to the goals of previous London and ongoing Paris exhibitions. Cole’s proposed shows also contrasted with contemporary ones, including the Vienna International in 1873. All countries and the British colonies could exhibit at South Kensington, but they could only exhibit what was called for each particular year, unless they could find a creative way to bypass the limits and exhibit what was not explicitly solicited. Some of the Australian colonies were able to do so by sending photographs of items not requested by Cole and by challenging the specific definition of ‘innovative.’ What was new in Brisbane, ![]() Queensland, for example, might not be new in London, and the colonial participants challenged who had the final determination of whether that item was truly innovative or not, and thus could be exhibited, or not (“Papers Connected with the Representation of Queensland” 3-5).

Queensland, for example, might not be new in London, and the colonial participants challenged who had the final determination of whether that item was truly innovative or not, and thus could be exhibited, or not (“Papers Connected with the Representation of Queensland” 3-5).

The story of those machinations and the exhibitions themselves begins with Cole’s scheme of exclusive annual exhibitions, rather than a single inclusive show every ten years or so, as had been the case in London and Paris. In fact, South Kensington had opened its doors in 1862 with the understanding of that second and expected schedule. One could see at least some of the major seeds for the alternative scheme being sown during the 1867 Paris Universal Exposition, the second French show attempting to exhibit the entire known world in all of its many material forms. Later critics, Watson among them, would also point to the connections between Paris and the subsequent South Kensington shows (30 Dec 10). Cole was in charge of Britain’s displays in the French capital and, as noted above, that work did not meet with universal commendation. His labors also provided a test case for how to organize, name and engage ‘the world,’ a case which provoked Cole as early as 1868 to consider the scheme of annual exhibitions at a meeting of Her Majesty’s Commissioners for the Exhibition of 1851. Reviews of the recent Paris show helped justify those changes. (A Special Report on The Annual International Exhibitions v-viii). At that point, Cole was proposing a series of five Annual Exhibitions, not the eventually bolder series of ten.

One additional consequence of England’s officially-sanctioned participation at the Paris Universal Exposition was the convening of a Parliamentary Select Committee to evaluate that experience and to ponder ways to acquire exhibits and other materials necessary to host subsequent exhibitions at the relatively new South Kensington complex. By this time, Paxton’s controversial Crystal Palace had moved to ![]() Sydenham and was home to a permanent collection, more like an amusement park and museum for its time than an international exhibition. A reproduction of the Pompeian Court, walkable gardens and dinosaur models–and not the most recent agricultural machines, consumer goods and paintings—attracted thousands of visitors.[2] South Kensington seemed to have been built in contrast for permanent art collections, the serious study thereof and periodic major decennial exhibitions of art and industry.

Sydenham and was home to a permanent collection, more like an amusement park and museum for its time than an international exhibition. A reproduction of the Pompeian Court, walkable gardens and dinosaur models–and not the most recent agricultural machines, consumer goods and paintings—attracted thousands of visitors.[2] South Kensington seemed to have been built in contrast for permanent art collections, the serious study thereof and periodic major decennial exhibitions of art and industry.

Cole’s decision to limit the type of exhibits for each year was an intentional contrast with the seemingly limitless cosmos of exhibits at Paris in 1867. The French show was intended to “hold up for a little while a mirror to mankind,” or the world; those in South Kensington were not intended to do so (“The Paris Exhibition,” 350). There was no appeal to excitement, or even what the public necessarily thought that it wanted. He knew himself what the public really wanted and needed, even if it did not express itself that way. Novelty was a key factor, preferably teamed with quality and utility. Newness in and of itself was sometimes sufficient to convince Cole that the object should be exhibited. Cole referred during his Parliamentary testimony to his experiences in Paris to advocate for “the purchase of a number of valuable works of art and of technical scientific interest” for display at South Kensington. Those would be exhibited in an effort to develop “the manufacturing interest of the country [Britain], and to the artistic and scientific instructions of the schools.” He knew what was needed! As we will see below, this perceived arrogance and its resulting commitment to the limited annual categories were considered by contemporaries among the causes of the shows’ failures.

As the editors of the Official Guide noted by their 1874 edition, Cole’s plans were well known by that time: visitors could expect art, decorations, furniture and “new discoveries and inventions (foreign as well as British)” this year as they had in the past few years, as well as “three or more special manufactures” not included in the previous shows. Those new exhibits included “the materials and machinery employed in each, as well as the manufactured goods” (1). One year, exhibitors were invited to display only pottery, woolens, and “educational works and appliances” (Cole, “Memorandum” 271). The next year, Cole and his commission solicited cotton, jewelry and musical instruments. This plan made the shows “international,” but not “universal” in the words of one catalogue editor, whose “Popular Guide” proceeded to list and describe many of the “upward of 8,000” exhibits at the 1871 show (Yapp 1). He included countries of origin and, if available, prices. Perhaps there was not everything under the sun at South Kensington, but there were numerous and varied examples of “novelty, invention, or special excellence” from around much of the globe (Cole, A Special Report vi).

Readers of the English press and visitors themselves could note, for example, toys, a llama, working machines and French art, among much more (“Sketches in the International Exhibition” 224-225). Some might take note of tobacco-pipes and drinking vessels from different periods and different countries, some ancient and some contemporary (Illustrated London News, 28 June 1873 602 and 20 September 1873, 280). Those were among the international displays in terms of time and space, but not universal as in exhibiting everything across time and space. In place of prizes, either monetary or not, Cole proposed expert’s reports and the eventual display of prize-winning exhibits at South Kensington, art schools and regional institutions.

Creative exhibitors, including those from the Australian colonies of Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland, circumvented the annual restrictions by including photographs of and essays about objects not specifically solicited for display during a particular show, and thus advertising more goods than officially expected and those that might capture the public’s intended eyes. The Colonial Architect in Sydney contributed a series of water colors and photographs illustrating public structures and manufacturing enterprises well beyond Cole and his commissioners’ list of solicited categories. (Catalogue of the Exhibits in the New South Wales Annexe). As noted above, some colonial commissioners also appealed to a looser definition of what was “new and innovative,” arguing that the definition should be based on what was new for Australians even if not so new for overseas exhibition visitors and judges. In the face of “the very confined scope as well as the short notice” to display, Queensland’s commissioners were particularly aggressive about what might be exhibited as “novel.” Before the Exhibition officially opened, they wrote to Cole and other English organizers:

It is fair, however, to presume that Her Majesty’s Commissioners, foreseeing that the more youthful and distant of the British possessions would be at a manifest disadvantage, intended some relaxation of the regulations to meet their case, and to allow for raw materials the qualification of ‘novelty,’ which, though not new in itself, should possess the recommendation of coming from a part of the world new to commerce as producing such material. (“Papers Connected with the Representation” 3-5)

Whereas such sentiment was driven in part by distance in its many forms and both political and social youth, one could not help but recognize that it was also driven by the consensus that as with earlier Exhibitions, “the resources of a new country are chiefly in the form of raw materials” (Catalogue of the Natural and Industrial Products of New South Wales 8). That was true in 1871 as it had been true the previous decade at the time of the colonies’ participation at the London Inter-national Exhibition, also held at South Kensington (Catalogue of Exhibits in the New South Wales Annexe). Those were the “elementary products, which Providence had placed within our reach” boasted the representatives of ![]() New South Wales (Ibid).

New South Wales (Ibid).

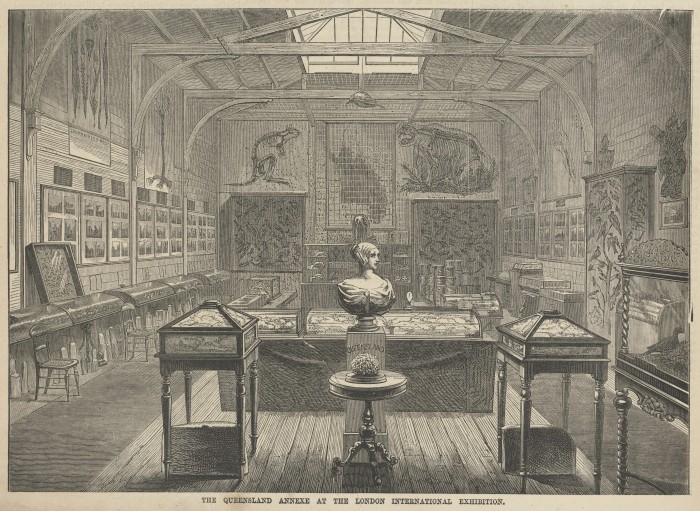

Images of Australian gold, flora and fauna, and Aboriginals were of particular interest to men, women and children walking around South Kensington. Those colonial displays also included photographs of manufacturing enterprises and of material exhibits that were too fragile, expensive, or large to ship to London for the shows. New South Wales and Queensland were again among the Australian colonies that most successfully stretched the Commissioners’ rules and limitations (Quarter-maine 40-55 and Bolton 20-27).[3] Richard Daintree, Queensland’s official Agent-General in London and Colonial Geologist, created an impressive collection of solicited and non-solicited items, and one that was proposed as a more permanent annex and then colonial museum at South Kensington (“Mr. Richard Daintree” 19 and “Queensland’s Annexe” 8). Many colored photographs accompanied the relatively new colony’s scientific, artistic and commercial samples, illustrating its tropical natural history, unusual geography and perhaps limitless mineral wealth. (See Fig. 2.)

Figure 2: Queensland’s Annexe at the London International Exhibition, 1871-74, Australasian Sketcher 15 April 1873, 8.

In the end, the annual scheme of selected exhibits was a gamble on Cole’s part, or, in his own terms, an “experiment.” Most, including Cole himself, would say he lost that bet and the experiments failed, but that is not to say that his policies and the resulting limited displays were not without praise and influence. That was more so the case in 1871, when the series of shows was a novelty. One London paper noted at the time that there was less space for manufactures, but more for the Fine Arts than at previous English exhibitions. The “principle of selection” was praised as not only a way to elevate “merit” and thereby ensure education and avoid favoritism, but also as a strategy to avoid “the confused mass of former International Exhibitions” (“Fine Arts in the International Exhibition” 450). There was high praise and equally high hopes that the “many complaints” raised by manufacturers and the “wearisome” days experienced by visitors could be avoided. Those would be replaced by “fairness and liberality consistent with the convenience and instruction of the public.”

Some of the selective courts were popular, including the one limited to European paintings, and it seems that the popularity was driven by the narrow focus of the courts in addition to the quality and newness of the exhibits. The Times reported that “the picture galleries were densely crowded all day” during the first official day of the 1874 International Exhibition even though most of the intended British and French masterpieces had yet to be hanged in the first floor’s Fine Arts Galleries (“International Exhibition,” 7 Apr.). Before their arrival, Belgian paintings, Italian sculptures and ![]() Brussels lace proved notably popular with visitors. The fine arts proved a magnet for such visitors, and the physical separation of art from other exhibits was repeated with success at future shows, both at home and abroad.

Brussels lace proved notably popular with visitors. The fine arts proved a magnet for such visitors, and the physical separation of art from other exhibits was repeated with success at future shows, both at home and abroad.

Other exclusionary choices led to sales and public expressions of approval by experts and authorities in their respective fields. That was the case with “The Indian Court” and its textiles, carpets, metalwork, ivory, jewelry and glasswork. Many of those and other South Asian objects were purchased by Cole and his staff for the permanent collections and display at the annual International Exhibitions. Initially on display within the main entrance of the Horticultural Gardens and the adjoining French gallery, the works were eventually exhibited in their own “special Court” (Yapp 39-40). John Forbes Watson was active there as one of the “Reporters” for India. His categories included “Fine Arts, etc” (Yapp xii).

The exhibits from India caught the attention of the press and the influential Art Journal during the second year. The latter’s contributor praised the “Oriental workers” whose labors were on display and who thought that the exhibits provided what Cole intended: “powerful aids” and “admirable models” for British craftsmen. The variety of textiles, ivory and wood works, and other art-wares were applauded for their beauty, ability to provide pleasure and utility, with potential contributions to British aesthetics and craftsmanship accompanied by larger potential reforms. The conclusion? “There have been no productions from any part of the world so fertile of instruction” (“International Exhibition Supplement” 3, 28-30, 59-60).[4]

The Times echoed such praise as the series of exhibitions ended, noting in particular the quality of the carpets and metalwork, but in the same column bemoaning some other exhibits “which are deplorable examples of the destructive effects of European notions upon Indian work” (”Indian Court” 6). The message was not as explicitly pro-Empire as perhaps some had envisioned the exhibits. Additionally, a contemporary thought that the displays were so impressive that they might provide the reason for Englishmen and women to stop calling South Asians “n-ggers” (“The Indian Court,” 1871, 288). Those two results do not appear among Cole’s stated intentions, but they suggest perhaps that art reform could provoke the reform, or “improvement” of common ideas, social relations and public policies.

Public expressions of praise for exhibits were not restricted to the European painting and South Asian art–ware displays. Italian porcelains were noted for their elegancy and ingenuity, although the pieces on display were not up to the quality of previous Italian art. The on-site correspondent for the Illustrated London News added that future shows might exhibit Italian work of regained quality (“The International Exhibition,” 1871, 120-121 and 145-146). Others at the time also noted the porcelains and potteries. Arthur Beckwith, an American civil engineer, published a catalogue and report on the “pottery” exhibits at the 1871 International Exhibition. One year after the show, Beckwith praised the “varied and comprehen-sive” displays not only for their own intrinsic quality, but also for what they seemed to promise “as only the first of the ten year programme” (100-101).

Whereas this “very complete collection of Pottery in all its branches” earned Beckwith’s applause because of its comprehensiveness, he was also careful to note the quality of the exhibits and “the machinery employed in its manufacture” (Beckwith 101). Invention, taste, mechanical excellence, and the superior technical qualities all captured the American’s attention and suggested that, at least in the case of the pottery exhibits, Cole’s objectives had been met. The collection was international, it included works of the highest quality and workmanship, and provided information about how the works were created and could be used. They were precisely the models intended to inform and reform public life. Cole’s mid-Victorian vision of labor, machinery, utility and beauty was realized in this “economy of space, time, and labor” on display at South Kensington’s international exhibition (63).

Beckwith’s praise was stronger than that of most other observers, but not unique at the time. His favorable impressions were echoed in the shorter narratives in popular handbooks, among which were Nelson’s Pictorial Guide-Book. Its editors concluded: “Pottery … is one of the two special manufactures presented this year; and the collection that has been brought together is everything that could be desired on the score of completeness and variety.” As if that were not enough praise, those editors continued to gush: “… it is by far the most comprehensive of any that has yet been made, including as it does, specimens of every conceivable species of ware, from the exquisitely ornamented vase to the familiarly common brick” (18). Written praise was accompanied by an illustration of the “Pottery Room,” noting well-dressed men, women and children clustered around open works and those in glass cases. One visitor at the fore-front holds what is presumably a guidebook or catalogue (Nelson’s n.pag.)

Looking back after the annual shows, a visitor might very well claim that she had experienced the world in total, just not at one particular show. There was a type of universality built into Cole’s vision. It was one that required patience and comparison, more patience and comparison than strolling through the halls in only two, or three days, or being entertained by the dinosaur models at Sydenham. One might call it “a close,” or “deep reading,” rather than a superficial one. South Kensington officials responded to what one contemporary termed the over-whelming “gigantic proportions” of the universal exhibitions by reducing the annual display of those “proportions” (Yapp 1). Art, science and industry were growing too quickly for everything to be displayed in one place at one time.

Rather, Cole’s scheme offered a dissected vision of that growth over an extended time period. This was a compelling argument for specialization, for inducing visitors to focus on particular products and compare the examples thereof, rather than being overwhelmed by thousands of different exhibits, a mass that often challenged the visitors’ capacities to judge, or even remember what they were supposed to judge. The individual value of each exhibit could easily by diluted if not annihilated by the intoxication of variety and number, although such balkanization prevented visitors from systematically connecting the various parts of the material and aesthetic worlds. Universal expositions, such as the Great Exhibition and the continuing Paris shows, invited those connections and networks.

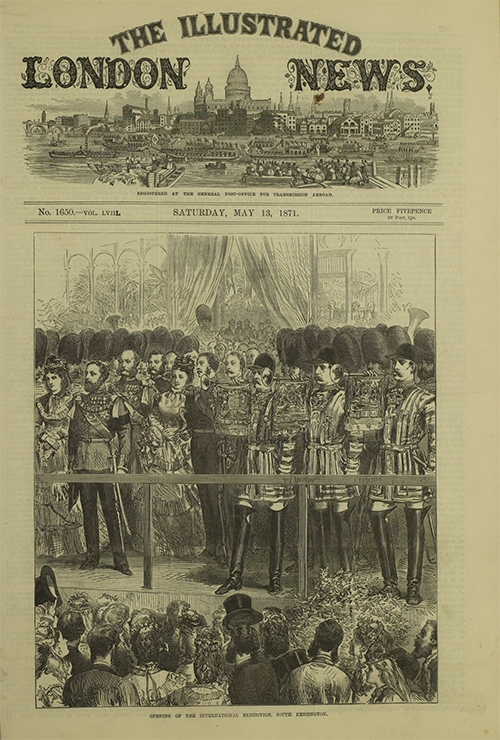

What began with a bang at South Kensington ended with a whimper. H.R.H. the Prince of Wales and other officials celebrated the shows’ opening in 1871 with a “State Ceremony” during a day of “bright and fine” weather (Fig. 3). Official presentations and declarations were made, a Psalm was read, and the day included a vocal and instrumental concert of Arthur Sullivan’s new cantata. The customary royal tour proceeded as scheduled (“Opening of the International Exhibition, South Kensington.”) Four years later, the final exhibition opened (and subsequently closed) without much notice (Cole, Special Report xviii). The Times reported that “[a]t 10’oclock … the doors of the International Exhibition of 1874 were opened without the slightest fuss, or ceremony.” Familiar ticket-takers and wardens greeted visitors, but the paper’s contributor noted that only “a third of the usual sum had been expended this year upon advertising” and “there was no special attraction held forth to the public.” The paper was optimistic that the first day’s attendance and the various attractions listed in the two columns would make the year successful (“International Exhibition” 7 Apr.). It was not.

Attendance dropped from a height of 1,142,000 in 1871 to only 467,000 by the close of the final show in 1874. Almost 15,000 of the latter showed up on Opening Day. Putting those numbers in perspective, the previous Paris Universal had been visited by 9 million men, women, and children. The two London-based International Exhibitions had welcomed about six million each in 1851 and 1862 (Findling and Pelle 413-417). Desperate for comparable or at least acceptable numbers of visitors, the official Commission at South Kensington reduced the entrance fees for artisans. That measure did not stop the descent into the proverbial “black hole” of neglect, deficit, and eventually disappearance.

The above is not to say that the International Exhibitions did not open with confidence and some optimism, although also with some bad luck, or that the halls were empty. It is also not to say that what was perceived by most as a failure revealed as much about the critics as it did about at least some of the raw material evidence. There were popular exhibits and displays that netted sales and positive reviews. The opening ceremony was well attended and praised, and the turnstiles turned. But the attendance numbers and the resistance of potential exhibitors did not tell a false tale. As John Forbes Watson noted at the time in a rather long letter to The Times: “… everybody will concur in the wisdom of putting an end to the present series of Exhibitions.” The official announcement in 1874 “has for the moment terminated the slow crisis through which the annual International Exhibitions at South Kensington have been passing” (9 June 1874 6).

How to explain that “slow crisis”? The commissioners’ timing for the shows had not been good, although such errors were not always their fault. Cole and his associates should have known that the ![]() Vienna International Exhibition scheduled for 1873 would be competition for South Kensington’s exhibitors and visitors. The official British commission had started meeting as early as October 1872 to organize and fund exhibits. It was the case that some potential exhibitors to both had to choose which one of the shows that year would deplete their limited resources, or they might divide their displays, leaving both shows with incomplete exhibits. That was the case with Watson’s Indian displays, as

Vienna International Exhibition scheduled for 1873 would be competition for South Kensington’s exhibitors and visitors. The official British commission had started meeting as early as October 1872 to organize and fund exhibits. It was the case that some potential exhibitors to both had to choose which one of the shows that year would deplete their limited resources, or they might divide their displays, leaving both shows with incomplete exhibits. That was the case with Watson’s Indian displays, as ![]() Bombay’s “valuable collection relating to the production and manufacture of cotton” was packed up and shipped across

Bombay’s “valuable collection relating to the production and manufacture of cotton” was packed up and shipped across ![]() the Channel to the busy Austrian capital (“The Vienna Exhibition” 86). With perhaps some irony, the India Office Reporter later praised exhibits at the Vienna show, after criticizing Cole’s exhibitions (On the Measures Required 10).

the Channel to the busy Austrian capital (“The Vienna Exhibition” 86). With perhaps some irony, the India Office Reporter later praised exhibits at the Vienna show, after criticizing Cole’s exhibitions (On the Measures Required 10).

On the other hand, it would have been surprising for the organizers in London to have foreseen the deadly Franco-Prussian War unfold as the gates of their show were originally intended to open in 1870, thereby creating not only a war cloud over what was supposed to be a celebration of peace and progress, but also making the participation of two key nation-states rather problematic. It was not expected that France and Prussia would find much time or resources for the International Exhibition as their soldiers were killing each other rather efficiently with the most advanced weaponry. The decision to continue the shows after 1870 in the face of that significant European war was not without controversy and expectations. One contributor to the London press was optimistic that the French would exhibit and “produce the best and prettiest things” once again after peace had been secured (Illustrated London News 2 September 1871, 199).

There were noteworthy design, quality and organizational issues. Cole himself admitted that there were serious “inconveniences,” including poor access to the galleries from railway stations and a “defective” refreshment room. “The public suffered [those and other] inconveniences accordingly, and became more and more alienated” (“A Special Report” xxxvii). As early as the second Exhibition in 1872 there were complaints about the “great falling off” in the contents and quality of key galleries and comments that works displayed at South Kensington had already been displayed at other public institutions. Those included “the ![]() Royal Academy and elsewhere” (Illustrated London News 17 August 1872, 166) In other words, quality and innovation were both suffering as stated objectives of Cole’s shows. French, Russian, Belgian and other foreign pictures included those that were mediocre or of “absolute badness” (“London International Exhibition. Foreign Pictures,” 70). By the final year, the Indian and French art collections included some works that were beautiful, but “not equal at all to former displays.” The decline in quality heralded the end of the shows (The Graphic, June 27, 1874, 619).

Royal Academy and elsewhere” (Illustrated London News 17 August 1872, 166) In other words, quality and innovation were both suffering as stated objectives of Cole’s shows. French, Russian, Belgian and other foreign pictures included those that were mediocre or of “absolute badness” (“London International Exhibition. Foreign Pictures,” 70). By the final year, the Indian and French art collections included some works that were beautiful, but “not equal at all to former displays.” The decline in quality heralded the end of the shows (The Graphic, June 27, 1874, 619).

Exhibition visitors expected guidance and advice. There were often no labels or lists to consult, so visitors were left to themselves or the good fortune of an informed companion. Crowds delayed access to sought-after galleries, notably the British picture galleries. The stairway up to the second floor was packed with anxious and sometimes bored visitors (Illustrated London News, 16 September 1871, 264). Appreciation of and inspiration from sculptures required good lighting. Alas, there was even poor lighting for the many sculptures. Such problems were expected at the birth of exhibitions in the 1850s, but were disappointing surprises to men and women visiting the grounds over twenty years later.

The distinction between international and universal did not seem to have been the issue for all critics as, at least in theory, the annual limit on exhibits provided focus and competition, much to the benefit of certain exhibitors whose works would be lost otherwise in the vast cosmos of universalism. One pictorial guidebook suggested that “the immense number of the articles accumulated” in previous universal exhibitions “prevented a close and critical examination of the collection either in its parts or as a whole” (Nelson’s 5). That vastness might have served some purposes, but not those of education and improvement, goals closest to Cole’s heart and soul. Limitless exhibits provoked awe, if not exhaustion, and not analysis and application. Limiting the exhibits might accomplish those objectives.

In the end, though, such goals were meaningful only if there were enough worthy exhibits in the displayed categories, those categories were of enough public interest and the building’s infrastructure encouraged access and understanding. Among others, Watson was not sure that Cole had selected exhibits in which the public was interested. In that case, the problem was not with the visitors and their expectations, but with the Executive Commissioner and his. That was only one among a constellation of issues, the consideration of which Watson wrote “may prove useful guides for future action” and return to what seemed like the happy union of the public and exhibitions in 1851 and 1862.

Contemporary Reflections and Criticisms: John Forbes Watson

Interest in society, or the public, and what might be termed, the public interest, was at the heart of Watson’s criticisms of the South Kensington annual exhibitions, among other shows. How could these shows be made popular, as they seemed to have been looking in the rearview mirror of history and memory? Watson understood that he was not alone in both despairing of the current conditions and aspiring for a return to exhibitions that were successful in all measures of that objective. By late 1872, he contended “the enthusiastic expecta-tions of 1851 have given place to a growing feeling of indifference, mingled with impatience on the part of the bulk of thinking men” (28 Dec 10). Like Trueman Wood in 1886, the India Office official feared some would use the failures to terminate all exhibitions. But Watson was relieved that as important as criticism was, “what is more important, it is being acted upon” in a way which sought to improve, but not eliminate, large-scale exhibitions. He intended to address “the very principle of the Exhibitions,” as the public questioned “their usefulness as public institutions” (28 Dec 10). What might have caused the public “revulsion” and how could that be turned to public engagement? How could Watson “act upon” the recent failures to better understand their causes and prevent their repetition?

Watson penned three extended letters in 1872 and 1874 to the London Times on the state of exhibitions, the public’s relationship to them, and how to improve both. What to do “about the revulsion which always follows exaggerated expectations?” (28 Dec 10) Those commentaries and recommendations were also made available in other published forms in the event that readers missed them in the newspaper or wanted to further reflect upon them (1873 and “Appendix C. – Letters on the Subject of International Exhibitions” 57-64).[5] Other sources picked up and mentioned the letters, suggesting a not insignificant public discussion. For example, The Architect (London) noted:

International Exhibitions.—Dr. Forbes Watson has published a letter In which he questions the wisdom of having every year an exhibition of new pictures and statues. This, he says, is pure art, and not applied art, and may be considered as sufficiently cared for independently of annual International Exhibitions. An international exhibition of the best works once in ten years would be sufficient. (Vol. 9, 4 January 1873, 12)

The core of Watson’s imploring was for English exhibition officials to better understand what the public was and what it wanted. Exhibitions were an important part of English society, but could only work if they were in sync with the public and if their organizers recognized that the public, or society, had changed and continued to change. Dynamic exhibitions were necessary for a dynamic modern society, and organizers were expected to know what would attract visitors and how often they would be attracted. Neither exhibitions nor society stood still. What could be done to ensure that exhibitions were profitable to exhibitors, instructive for the general public and useful to the nation, if not beyond the nation’s borders? Those effects were not to be ephemeral, or airy, but “traceable and tangible” (30 Dec 10). The three letters articulated a logical narrative of why the Great Exhibition had been so popular, why the current South Kensington ones were not, and how exhibitions could be saved and could function for the public good as complements, not competition for, technical and trade museums.

John Forbes Watson was a well-known exhibition commissioner and exhibitor at shows in England and abroad in his positions as Reporter on the Products of India for the India Office and Director of the India Museum in London. (See Fig. 4) He spoke with authority and experience as he entered the public conversation about the annual international exhibitions and exhibitions in general. Watson’s resume included organizing and sometimes personally overseeing Indian exhibits at the London International in 1862, the Vienna International eleven years later and a significant number of other exhibitions as distant from the India Museum as ![]() New Zealand. If Cole or other British executive commissioners needed Indian exhibits, it was to Watson that they commonly turned. Trained in medicine with a degree from

New Zealand. If Cole or other British executive commissioners needed Indian exhibits, it was to Watson that they commonly turned. Trained in medicine with a degree from ![]() Aberdeen and a stint as Army Surgeon in Bombay, he brought that background to his efforts to organize, explain, represent and often sell India’s commercial products. Those efforts included the official exhibition catalogues of the Indian Departments at many shows and reports on the scientific names and uses of what were commonly called at the time “economic plants.” Such plants included textiles, tobacco and cotton.[6]

Aberdeen and a stint as Army Surgeon in Bombay, he brought that background to his efforts to organize, explain, represent and often sell India’s commercial products. Those efforts included the official exhibition catalogues of the Indian Departments at many shows and reports on the scientific names and uses of what were commonly called at the time “economic plants.” Such plants included textiles, tobacco and cotton.[6]

Watson’s critiques were available while the annual shows were up and running, if we can use that term, and offered systematic and extended discussion of what was wrong and what could be fixed with exhibitions, as did Cole’s own lengthy official report, published in 1875, a year after the final exhibition. Picking up and riding with what he noted was a wave of “negative criticism,” the India Office official discerned in that criticism “a significant change in the public feeling on this subject [international exhibitions, not only Cole’s shows]”(28 Dec 10). He tried to explain “why it is that the present London exhibitions had so signally failed to achieve what measure of practical success was realized by” previous exhibitions and how those causes might very well not be unique to the failed South Kensington events. Unlike in the cases of their predecessors, or Watson’s and others’ memory of those events, including, not surprisingly, the Great Exhibition, the later Victorian public did not attach “a transcendent importance to the idea of International Exhibitions.” This was to Watson not a particularly idle or passing matter, but, rather, “it is of the utmost importance for the future of International Exhibitions” that the causes of that decline in interest be understood and addressed. He was thinking in what we would consider psychological, material and social terms about exhibitions, the public and the relationships between the two.

Watson had an historical and sociological sense of those relationships. 1871 was most certainly not 1851 in nearly all ways, and Watson thought that recognition of such changes could be used to save exhibitions, so that they could represent and gain from the new “public feeling” and not ignore it. In this way, he did not disagree with Wood that the annual shows had been out of step with the times; he did not, though, focus blame on Cole, as Trueman Wood would do over ten years later, with an almost unrelenting criticism of the Executive Commissioner (Wood 636-637). Watson’s critique addressed both what was intrinsic to the exhibition scheme and the way that the scheme was carried out, a distinction that at least one important twentieth-century scholar would draw (Luckhurst 134-135).

Watson noted how exhibitions were negatively affected by larger economic and materials changes since The Great Exhibition. There was a set of broad new external challenges: “the vast increase of international commerce…the rapid spread of railways, and telegraphs, the establishment of agencies…and of extensive -” warehouses (I2 Dec 10). Modern commerce and infrastructure had replaced medieval fairs, and now even more modern commerce and infrastructure were replacing the earlier exhibitions. Others might celebrate those developments as making it possible to have larger and more international exhibitions, but Watson was not among that crowd. Railways made possible the annual shows in the early 1870s and railways also undermined them.

It was not only trade and technology that had changed in Watson’s view, but also “international relations.” Basking in the golden hues of nostalgia, the Great Exhibition was remembered as the focal and meeting point for peace and trade during “the undeveloped state of international relations” in 1851 (28 Dec 10). Those relations were quite “developed” by 1871—trade agreements and disagree-ments, the Wars of German Unification, many imperial ‘small wars’ across the globe, the American Civil War—so exhibitions served a different international purpose in a new and different world of international relations, a world filled with the scrambles for national, regional and world power. The relative European and British peace of 1851 had been replaced by the increasingly martial relations of the later 1860s and the 1870s. As Wood remarked over thirty years later, “The First World’s Fair did not inaugurate a reign of peace [as many associated with it]…Still, it did its work well for all that” (631). Exhibitions could still serve the purposes of peace, but had to change according to the changing world in order to so. In this case, Watson and Cole did not disagree on the greater purposes of exhibitions, but did not agree on how to achieve those purposes. Although arms companies exhibited weapons, it would be a far cry to consider Cole or Watson as “war-mongers,” or thinking of exhibitions as promoting militaristic relations.

Those two exhibition officials could also agree that exhibitions were no longer perceived as novelties, great and unprecedented events on the public and private calendars, as they allegedly had been for the previous generation. Commissioners and exhibitors could not simply assume that exhibitions by the 1870s would be an effortless magnet for public enthusiasm. A recent scholar has helpfully written about this “exhibition fatigue,” or what he considers the loss of public interest and political will to stage yet one more international exhibition (Geppert 201-202 and 206-218). Watson noted at during the second Annual Exhibition “a growing feeling of indifference, mingled with impatience,” either one of which on a large scale was a death sentence for exhibitions (28 Dec 10).

No subsequent event could quite replace the first, or Great Exhibition, a fact recognized by Watson, even if one factors in some skepticism about enthusiasm for the ![]() Crystal Palace or at least filters out the not insignificant opposition and criticism in 1850 and 1851.[7] Memories of exhibition legacies were quite strong well after the events. The “novelty of the undertaking” contributed in Watson’s view to the success of such earlier shows, particularly when one recognized the “intangible influence of the mere start, shock, or impulse,” all of which wears off when exhibitions and other such “shocks” become expected and routine (28 Dec 10). Here was a psychology of exhibitions. There was little if any “impulse” or buzz in 1870, in part because South Kensington had already hosted shows and there had been inter-national exhibitions in England, France and the United States by then.

Crystal Palace or at least filters out the not insignificant opposition and criticism in 1850 and 1851.[7] Memories of exhibition legacies were quite strong well after the events. The “novelty of the undertaking” contributed in Watson’s view to the success of such earlier shows, particularly when one recognized the “intangible influence of the mere start, shock, or impulse,” all of which wears off when exhibitions and other such “shocks” become expected and routine (28 Dec 10). Here was a psychology of exhibitions. There was little if any “impulse” or buzz in 1870, in part because South Kensington had already hosted shows and there had been inter-national exhibitions in England, France and the United States by then.

Cole and Watson understood this problem and each in his own way sought to promote novelty, or something unusual about the next exhibition. Watson wanted to rekindle that “impulse” in 1851 that “acted like giving sight to the blind” (28 Dec 10). This was a nod to what we might consider the popular psychology of exhibitions and what “impulses” they encouraged and exploited. In Cole’s case, he proposed the novelty of the ten-year scheme of displaying the best each year in a limited number of categories. The novelty of the scheme was not Cole’s only motivation, but it was a welcome attribute. Novelty when coupled with practicality were at the forefront of Watson’s exhibition advocacy. He had the experience to support that position, and to recognize that novelty was not an objective without cost. It was also probably not one to be applied to art. “Indeed, I would question the wisdom,” he wrote at the end of 1872, “of having every year an Exhibition of new pictures and statutes” (30 Dec 10). The public wanted novelty in machines, trade and consumer goods, and perhaps the practical arts, but not in the realm of “pure art.” Contemporaries also pondered whether the novelty of exhibits substituted for a more enduring characteristic, such as quality? Should one display a work of art or mechanical innovation because it was novel, or because it was of high quality? Cole would have contended that both sets of objectives were achievable. Others did not always concur.

John Forbes Watson, Exhibitions and Public Life

What else did Watson think were “the organic causes of the existing discontent with Exhibitions,” the query he asked in the first of his three letters to the editor of the London Times? (28 Dec 10) The “faults of management” was one possible answer, but, even if true, that did not “account for the magnitude of the reaction” against the South Kensington shows. Wood might have no love or affection for Cole, but antipathy for the Executive Commissioner was hardly the major cause of popular indifference or discontent. Watson and Wood agreed that the management was inadequate, and Wood would have used stronger terms, but there was more afoul. Even competent Commissioners had to deal with “a restive public,” rather than the allegedly enthusiastic and “willing” earlier public. Could Cole’s successors successfully “persuade, even coax, an unwilling constituency?” The challenge for Watson was to articulate the Exhibitions as a “public institution,” which can “manifest incontrovertible and tangible public utility” (28 Dec 10). He thought that the challenge had been overcome in 1851; not in 1871, and even less so during the subsequent years of Cole’s annual shows.

Watson argued most poignantly that the “public” had changed since the mid-century point and that International Exhibitions did not work in ways that resolved, reconciled and developed together the different interests and parties that comprised his understanding of “the public,” or “the public interest.” That public in terms of its relationships to Exhibitions at the time of the Crystal Palace had included “producers, traders, and consumers,” or what one might consider a market view of the public in keeping with early political economy. Rather, in a later-Victorian vision, one generation later, Watson understood a “wider sense” of the public “the private community, the intellectual, artistic, and material progress of which is aimed at; and, finally, there is the State, which may and should derive from these great undertakings [Exhibitions] certain definite conclusions, shaping policy and influencing its legislation” (28 Dec 10) This vision occupied a via media between Cole’s more laissez-faire one and the quasi-corporatist one held by others at the time. Not surprisingly, Watson’s comments echoed in many ways the ideas of John Stuart Mill at the time about the relations of society, the State, the market and the individual. Patrick Geddes would, in turn, echo Watson’s claims, recommending in his Industrial Exhibitions and Modern Progress that “an ideal exhibition” required by the later 1880s “not only the producer, but the consumer; not only the capitalist, bur artisan; not only artist, but thinker.” They all “must have a say, and bear a hand” if an exhibition were to succeed (16).

Everything connected to the exhibitions should be done in the name and interest of the public, a public that included civil society, the individual and the State, and not necessarily in opposition. Watson understood exhibitions as succeeding or failing to the degree that they appealed to that vision of the public and, in turn, the health of the public was tied to the success or failure of exhibitions. This was a two-way relationship. Having a “public utility” was essential for the success of an exhibition and exhibitions were at the heart of a functioning public life. But that success required exhibition advocates and participants to understand the public and utility, and how they were connected. Not one, or the other, but both, and both in a dynamic relationship. This was a sociological understanding of exhibitions and although articulated by Watson, certainly not unique to that India Office official.

Cole and the South Kensington commissioners were locked in their mid-Victorian world: for Wood, that meant obsession with education rather than paying attention to entertainment; Watson would have tweaked that argument to suggest that the shows were attempting to convince a public whose structure and interests were no longer those of its predecessors. Watson’s letters were a wake-up call that society had changed, not Wood’s reminder that entertainment and education had always been dueling objectives. Constituent parts of the public had changed and so had their expectations for exhibitions. With such a changed society, one could note that the goal posts had moved. Could exhibition commissioners move with them? Wood would echo Watson’s concerns about “the management,” but not draw out his profound and foundational arguments. This was about far more than Cole’s administrative style and ego, far more than about whether to highlight and promote technical education. This was about profound change, changes in society, the individual and their relationships. This was an increasingly post-Classical Liberal view of the world. Cole’s exhibitions were stuck in a Classical phase.

Watson was not shy. For him, society and the public were comprised of “several well-defined separate interests,” and the interests of such “different sections” of public life were not only “different,” but also “in some measure conflicting” (28 Dec 10). It was not the market or politics alone that resolved those conflicts, but “spasmodic, temporary” exhibitions and “permanent” trade and technical museums. The latter were “efficient and practical,” unlike Cole’s South Kensington exhibitions which were ending when Watson penned his final letter (9 June 6). The shows and institutions represented not only all of the differing and competing interests, but also offered an example of how they could coexist and, at times, be reconciled. In this way, exhibitions were not only about the quality of art, or selling goods to make money, or even promoting a sense or idea of the nation at a time when it seemed that everyone everywhere wanted to be a nation. Exhibitions were about society itself, about how individual and collective interests and behavior publicly converged without coercion.

Watson was not resigned to the death of popular exhibitions. He argued, though, in no uncertain terms that their purposes could by “obtained by other means” if exhibitions did not change and be “more in accordance with the wants and tendencies of present times.” Exhibitions should not lose their fundamental characteristics—“spasmodic, temporary efforts…for the promotion of a public end”—but in keeping those, search for “novelty and competition,” not “systematic completeness or steady usefulness.” In contending such, Watson offered a promising compromise between the assertions and goals of Cole and Wood. Avoid trying to educate everyone about everything, but do not avoid competition. Exhibitions could be educational and entertaining if organizers recognized the ways in which the public wanted to consume that duo of “civilizing” goals (9 June 10).

Previously, exhibitions originated ideas, products and behavior; they were creative. That time had passed, though. “Individual action has outstripped collective action, and the Exhibitions at present do not originate, but merely register, the change wrought by other agencies” (28 Dec 10). There were now in the 1870s many more such “agencies,” particularly in “the commercial world,” and other popular ways to “register” such agencies and changes. Commissioners could rise to the challenge if they recognized those changes and the consequent problem. Exhibitions had to be more than representational, more than duplicating earlier shows, or the other magnets for public attention, such as museums. It was time for Exhibitions to be creative again. How could that goal be achieved? How could organizers, exhibitors and visitors collectively realize what Wood claimed a decade later were “the elements of promise still existing in the [Exhibition] movement” (633).

Watson offered some practical advice. “The Exhibition must be at once profitable to the exhibitors, instructive to the public, and useful to the community at large” (30 Dec 10). This would require selection, organization and description which is not “indiscriminate,” but, rather, takes into account the special needs of each of those interests and the collective public interest (26 Dec 10). Yearly shows for specific types of exhibits would work, particularly if one waits ten years for a repeated category. Paintings, sculpture and “pure art” need not be included every year, whereas science and machines could be. Having said all of that, it was most important to have some “systematic action” to ensure that the exhibition had a measurable and noticeable effect on society and the public. That might be secured by exhibiting what that public wanted. Watson thought information and knowledge “of the laws of health and other matters directly affecting the welfare of the community” would claim more public interest than machines-in-motion (30 Dec 10).

One other way to achieve successful exhibitions was to recognize that, as Watson put it, “exhibitions are in every respect the reverse of museums” and that they both needed the other. This was a distinction with a difference, and Watson advocated for both, but did not blur the gap between a permanent institution with a complete and comprehensive collection and the “spasmodic” exhibition offering what was novel and limited. Each Victorian institution had its own particular “influence” on and relationship with the public (9 June 10). Museums and exhibitions offered the most successful advertisements for different types of objects. That was particularly true for trade and technical museums. Cotton, wool and metals deserved their own museums in their own home towns of, respectively, Manchester, Leeds or Bradford, and Birmingham (30 Dec 10).[8]

Criticism in the 1880s: South Kensington Shows in the Rearview Mirrors

Trueman Wood picked up the criticism of Cole’s shows over ten years after the last one closed in his essay on “Exhibitions,” published at the time of the more popular and successful topical, or thematic annual South Kensington exhibitions. The Secretary of the Royal Society wrote in 1886 that the first annual show in 1871 “was so dismal a failure” and it was followed by equally failing ones, that they were “thought to have put a stop to exhibitions in this country, at all events for a long time”(Wood 636-637). Whether or not Cole’s failures were the reason, the British international exhibition calendar was relatively empty between 1874 and the early 1880s. The British participated at major shows in the Australian colonies, France and the United States, but did not host such shows for nearly ten years. The success of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition at the time of Wood’s reflections suggests that the warning was probably at least partially correct until South Kensington opened up its thematic gates to men, women and children interested in Fisheries (1883), Health (1884), Inventions (1885) and the British Empire (1886).

We can suggest some connections between Wood’s criticisms and reflections regarding the shows in the 1870s and the successes he engaged in during the 1880s. Looking back, what did Wood consider the causes of Cole’s failures? Why did participants lose interest, or why was that interest dwarfed by the attention inspired by other international exhibitions? Wood had a series of explanations and he was not bashful about sharing them in print. He blamed “the unsuitable” building and its “one enormous passage,” suggesting that “visitors were sick of its interminable length before they had got half round it” (636). One M.P. echoed Wood at the time by complaining that Cole “was the only despot that could have made a procession walk a mile” (qtd. in Cole, Fifty Years 268).

There were also restrictions on the movement of visitors, both to and within the South Kensington complex. Their access and approaches among the various galleries were not as Cole had intended them to be: “free and uninterrupted,” regardless of the length of the halls and sizes of the courts themselves. There was no expected “large place where visitors might assemble and promenade,” as the Executive Commissioner noted was present at previous and later international exhibitions (Cole, Special Report xiv-xvi; “Memorandum” 268). Such criticisms were expressed at the time of the shows in the popular press and in Watson’s published letters. The India Office official Watson had rather strong opinions about the display cases and physical layout of exhibition halls and museums. The architectural plan mattered, and that included the necessity of “a spacious central hall” (9 June 6).

Those were not the first or the last criticisms of Captain Fowke’s South Kensington exhibition halls, given the popular and unflattering nickname of “The Brompton Broilers.”[9] It was, in fact, a rather large and long exhibition space, totaling about one hundred acres, whereas Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace and associated environs in 1851 had been closer to a manageable twenty total acres. Officials learned their lesson and reduced to under twenty-five acres the Colonial and Indian Exhibition, praised by Wood in 1886. That would have pleased the angry M.P., although one can only imagine the depths of his displeasure walking the 215 acres at the Paris Universal Exposition in 1867 (Findling and Pelle 413-417). Bigger was not always better for this generation of English exhibition advocates and visitors, a reminder that public culture required management and some semblance of rationality.

Wood recognized the commercial advantages of exhibitions, but they were apparently no longer as attractive to business and manufacturing interests as previous shows had been. There were now so many other ways to secure consumers and profits that advertising by exhibiting was a harder sell for the commissioners to secure. English manufacturers still turned to overseas shows and in the case of Vienna in 1873 that opportunity undermined rather than supported Cole’s plans. The “multiplication” of exhibitions and in some cases, their overlap, was “not popular with manufactures,” noted Wood (637). How could commissioners have convinced businesses to exhibit in London while also doing so in Vienna?

Wood also disagreed with how exhibitors should be recognized and awarded. Cole thought that an expert evaluation with recommendations was enough. His original plans called for “competent Judges” to evaluate exhibits with published “discriminating reports,” but that “no prizes should be awarded” (“Memorandum Upon a Scheme” 269) Not according to Wood. Exhibitors expected prizes and awards, which they could use as part of their advertising after the event. Those were to Wood “testimony of his [the exhibitor’s] success” in a way which professional, even if “expert,” advice could not provide, or could only truly provide after a series of tests. Exhibitions were not organized for such tests (644-645). The recipients, or exhibitors were thought of differently by the two exhibition advocates: Cole assumed that the formal report would help the exhibitor improve his product, whereas Wood understood that a prize would help him sell that product. In keeping with that goal, Cole and his fellow commissioners organized a series of technical lectures and provided a handful of scholarships (“A Special Report” xxxii). One reading of Watson’s published views is that he thought both goals could be realized by displaying temporarily at an exhibition with an award and more permanently at a technical museum with professional information provided (9 June 6).

The 1874 show had included jurors and tests, but the Royal Society allegedly ran out of funds before the reports and citations could be prepared and distributed (Wood 644). One can speculate about the cause of that apparent dearth, although it can be noted that Cole was consistently opposed to prizes as he prepared for the annual shows and they unfolded. Perhaps that personal view influenced the available funds? Cole later admitted that “prizes are attractive and exciting,” points with which Wood would have agreed, “although theoretically and philosophically indefensible” (“Work with International Exhibitions” 271). That latter point is one with which Wood and many others disagreed. That being the case, Wood was still not done with his criticisms.

The Royal Society of Arts official continued in 1886 that there had been too much “red tape” for exhibitors and not enough garden space for visitors in the early 1870s (636). That was most notably the case after the Horticultural Society withdrew from the International Exhibition and subsequently charged visitors an additional fee to enter its part of the South Kensington complex. The Society’s actions were later blamed by Cole and historians as one of the reasons for visitors’ complaints and for the financial debt (A Special Report xiv-xv and xxxvi-xxxvii). And, Wood was still not done, for there was one more compelling reason for failure in his mind, but he had to wait a few years after the shows to express it.