Abstract

The Grosvenor Gallery (1877-90), founded by Sir Coutts Lindsay and Lady Caroline Blanche Elizabeth Fitzroy (a Rothschild on her mother’s side) on 135-37 New Bond Street in London, generated a seismic change in the conventional Victorian art world in its exhibition of then avant-garde artists like Edward Burne-Jones, James McNeill Whistler and G. F Watts, and other leading members of the Aesthetic Movement, such as Frederic Leighton. Its unique methods of display, invitations to exhibit, support of women artists, and stunning building and interior decoration marked its ties to the Aesthetic Movement and its challenge to the Royal Academy.

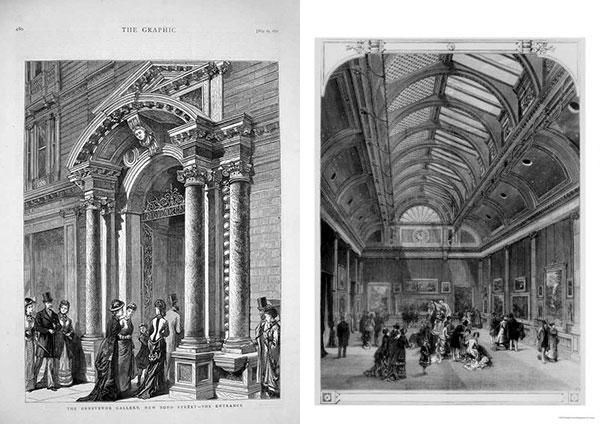

![]() The Grosvenor Gallery (1877-90; fig. 1), founded by Sir Coutts Lindsay and Lady Caroline Blanche Elizabeth Fitzroy (a Rothschild on her mother’s side) on 135-37

The Grosvenor Gallery (1877-90; fig. 1), founded by Sir Coutts Lindsay and Lady Caroline Blanche Elizabeth Fitzroy (a Rothschild on her mother’s side) on 135-37 ![]() New Bond Street in London, built by G. H. and A. Bywater (Newall 10), was an immediate success. It was recognized for the unconventional art it displayed, its unique display of paintings, and its beautiful building, all of which appeared as a challenge to the Victorian art world, especially to the

New Bond Street in London, built by G. H. and A. Bywater (Newall 10), was an immediate success. It was recognized for the unconventional art it displayed, its unique display of paintings, and its beautiful building, all of which appeared as a challenge to the Victorian art world, especially to the ![]() Royal Academy of Arts (RA, founded by royal charter in 1768), which dominated the British art world since its founding and is still active today. Both Lindsays were themselves amateur painters, and Caroline was an accomplished violinist.

Royal Academy of Arts (RA, founded by royal charter in 1768), which dominated the British art world since its founding and is still active today. Both Lindsays were themselves amateur painters, and Caroline was an accomplished violinist.

Before the Grosvenor, there were other exhibition venues outside the RA: The Royal Watercolour Society (the “Old Watercolour Society,” 1804, and sometimes reformed under other names); the British Institution (1805-67) whose members were aristocratic patrons, not artists; the Royal Society of British Artists (1823, granted Royal charter in 1887); the British Institution (1870-1876); and later galleries like the ![]() Dudley Gallery (1865-1918?) that had a unique open exhibition policy. These institutions, some created in opposition to the RA, maintained much of the RA’s style of exhibition display and membership requirements: works were hung cheek to jowl and floor to ceiling, artists applied for membership and artist members had to contribute new works every year for the annual exhibitions. In addition, artists’ professional societies proliferated from the 1870s on, and these, too, incorporated practices like those of the RA for membership and exhibition (Codell, 1995).

Dudley Gallery (1865-1918?) that had a unique open exhibition policy. These institutions, some created in opposition to the RA, maintained much of the RA’s style of exhibition display and membership requirements: works were hung cheek to jowl and floor to ceiling, artists applied for membership and artist members had to contribute new works every year for the annual exhibitions. In addition, artists’ professional societies proliferated from the 1870s on, and these, too, incorporated practices like those of the RA for membership and exhibition (Codell, 1995).

The Grosvenor was distinct from these venues. Although technically a commercial gallery, Lindsay refused to permit any sign that the Gallery was concerned with sales. From the start, the Grosvenor became associated with the Aesthetic Movement (also called Aestheticism), less a movement really than a loose group of artists beginning in the 1860s who shared several aesthetic beliefs: that art’s function was not didactic or historical, that the dominant function of art was to emphasize the aesthetic with a focus on color, form and composition (“art for art’s sake”), and that art embraced the crafts, interior decoration, and dress, as well as the “high” arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture. These artists eschewed domestic narratives of genre painting and avoided all didactic content. Some of them engaged in narratives of classical mythology, one of their signature subjects, represented in generalized classical allusions to dress, interior decoration and settings without concern for archeological or historical correctness. Many of these artists were also active in decorative projects and in blurring the distinction between painting and decorative arts (furnishings, crafts). While Aesthetes proclaimed a divorce from commercial and market motivations, scholars of Aestheticism in art and in literature, such as Jonathan Freedman, have long recognized the movement’s prominence in the retail of furnishings, decoration, textiles, stained glass, and dress across many venues from Morris’s various decoration companies, to the famous retailer ![]() Liberty’s Department Store and to myriad advertisements in art periodicals.

Liberty’s Department Store and to myriad advertisements in art periodicals.

In the RA, art works by the hundreds were jammed together on high walls. In the Grosvenor, works hung uncramped in individual wall bays, one painting per bay, and a single artist’s works would be grouped together along a wall, a display method that was almost unheard of outside of the new dealers’ galleries in which single works or works by one artist were displayed. This method of display, now associated with modern museums, encouraged contemplation of individual works of art, in a kind of sublime interaction between viewer and painting endorsed by Oscar Wilde in his essay on the first exhibition. As Colleen Denney notes, the first exhibitions were inscribed by a classed way of viewing art that explicitly eschewed the “vulgar” Academy, in Wilde’s assessment, much like the views of Basil Hallward in Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray (Denney Ch. 1 essay in Casteras and Denney 21). Among the most common Grosvenor subjects were medievalist stories, classical myths or imagined scenes in classical settings, allegorical works sometimes designated as Symbolist works (e.g., G. F. Watts), and scenes of rural life. Among the conventional genres, the Grosvenor displayed many portraits and landscapes, though these were not always done in conventional or realist styles.[1]

The hanging style was part of a larger aesthetic of interior decoration reflected in the Gallery’s rooms and architecture. Considered by many a “palace of art,” a term first used for the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition in 1857 and the title of a poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson, the building was as carefully constructed as its exhibitions. The doorway had been formerly the doorway of the Church of Santa Lucia in ![]() Venice by Andrea Palladio (1580; destroyed), fitting the building’s Renaissance-revival style. Walter Crane called Lindsay a modern Lorenzo di Medici, a reference also made in a Punch cartoon (Denney Ch. 1, 19). Inside, the Gallery appeared like an aristocrat’s picture gallery in a palace or country house, with green Genoan marble in the hall, Ionic pilasters and wide stairs with sculpture pedestals. A dining room below the main gallery was for banquets. Gilt capitals and a nave with gothic-like buttresses above blue bays with the phases of the moon in the main gallery completed the elegant decoration. Walls were divided by pilasters and covered with scarlet Lyons silk damask (Newall 11). Giles Waterford describes the entrance and stairway as creating “processional routes . . . the stimulation of a sense of occasion” for the viewer’s arrival (Waterford 28). In line with the aristocratic spaces, Lindsay had a billiards room and a smoking room for gentlemen, buffet bars and the restaurant for all viewers, an innovative circulating library in 1880 with an extensive collection of books and music, and electric lights installed in 1882.

Venice by Andrea Palladio (1580; destroyed), fitting the building’s Renaissance-revival style. Walter Crane called Lindsay a modern Lorenzo di Medici, a reference also made in a Punch cartoon (Denney Ch. 1, 19). Inside, the Gallery appeared like an aristocrat’s picture gallery in a palace or country house, with green Genoan marble in the hall, Ionic pilasters and wide stairs with sculpture pedestals. A dining room below the main gallery was for banquets. Gilt capitals and a nave with gothic-like buttresses above blue bays with the phases of the moon in the main gallery completed the elegant decoration. Walls were divided by pilasters and covered with scarlet Lyons silk damask (Newall 11). Giles Waterford describes the entrance and stairway as creating “processional routes . . . the stimulation of a sense of occasion” for the viewer’s arrival (Waterford 28). In line with the aristocratic spaces, Lindsay had a billiards room and a smoking room for gentlemen, buffet bars and the restaurant for all viewers, an innovative circulating library in 1880 with an extensive collection of books and music, and electric lights installed in 1882.

The Lindsays’ interest in the importance of decoration is also reflected in the artists who exhibited at the Grosvenor for whom decoration was an important part of their work and ideas—Edward Burne-Jones, James McNeill Whistler, Frederic Leighton and William Holman Hunt, for example. Clearly intended to appeal to an aristocratic and well-to-do section of the public, nonetheless Lindsay advocated opening museums and galleries on Sundays, a much-debated subject in Britain, although a regular practice on the Continent. Sunday openings would make the Grosvenor available to all classes.[2]

The first exhibition in 1877 was a sea change in the art world and some, like Oscar Wilde who reviewed it for the Dublin Review, recognized its dramatic importance. The artists who exhibited were not regularly seen at the RA or in public exhibitions, as some of them had rejected exhibitions altogether. Whistler’s Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1: Portrait of the Artist’s Mother had been rejected by the Academy in 1872 and then, after others complained, put into that RA show, causing Whistler to refuse to show his works there again. Burne-Jones, who resigned from the Old Water-Colour Society over its decision to reject Phyllis and Demophoön in 1870 for its male nudity, withdrew from exhibiting for a while. At the Grosvenor‘s first exhibition, Burne-Jones’s eight paintings took up much of one wall in the West Gallery. George Frederic Watts, who had permitted himself to be enrolled in the Academy by others, was compared to Michelangelo in Oscar Wilde’s review of this first Grosvenor exhibition. Watts, Burne-Jones and Whistler all enjoyed a meteoric rise after the 1877 Grosvenor show.

The first exhibit included works by artists who were identified as anti-establishment. This list is not comprehensive, but includes some important examples that marked the Grosvenor‘s immediate success and notoriety (see Christopher Newall for a complete list of all paintings and artists who exhibited at the Grosvenor):

Edward Burne-Jones:

The Days of Creation

The Mirror of Venus

The Beguiling of MerlinJames McNeill Whistler:

Nocturne in Blue and Gold

Nocturne in Blue and Silver

Nocturne in Black and Gold (The Falling Rocket)

Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2: Thomas Carlyle praised by Wilde in his reviewGeorge Frederic Watts:

Love and Death

The Hon. Mrs. Percy Wyndham

Lady Lindsay (ofBalcarres)

E. Burne-Jones, Esq.William Holman Hunt, a co-founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB):

The After-Glow in Egypt

An Italian Child

One the Plains of Esdraelon, above Nazareth

A Street Scene near CairoJohn Everett Millais, another PRB co-founder, and later RA and then President of the RA:

The Marchioness of Ormande

Countess Grosvenor

Lady Beatrice Grosvenor

Lord Ronald Gower

“Stitch, stitch, stitch”—Hood’s “Song of the Shirt”Albert Moore, a leading Aesthete:

Sapphires

Marigolds

The End of the StoryJohn Roddam Spencer Stanhope, among many second-and third-generation Pre-Raphaelites:

Eve Tempted

Love and the Maiden

On the Banks of the Styx

The Mill

The Grosvenor invited artists to exhibit and was a commercial gallery, so there were no memberships. Invitations were based on style, so that some Academicians including Frederic Leighton, later President of the Royal Academy, exhibited there as well. Among the RA members (Royal Academicians or Associates) exhibiting at the first exhibition were:

Frederic Leighton

Portrait of Henry Evans Gordon, Esq.

An Italian Girl

Two studiesLawrence Alma-Tadema

Sunday Morning

A Seat

A Mirror

A Bath

Phidias showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friend

Sunflowers

Tarquinius Sperbus

A PortraitEdward Poynter whose 11 works in 1877 included Andromeda, Mrs. Burne Jones and Proserpine.

Among other RA members who regularly exhibited at the Grosvenor were George Clausen, Herbert von Herkomer, Valentine Prinsep, William Blake Richmond, and American John Singer Sargent. Sculptors who exhibited included William Hamo Thornycroft (RA), Edgar Boehm (RA), who exhibited from 1877-89, American Auguste Saint-Gaudens, and French modernist Auguste Rodin in 1882 (A Bronze Mask). Late-century artists who blended Pre-Raphaelitism in the 1880s with Aestheticism included Walter Crane, John Melhuish Strudwick, Marie Spartali Stillman, and Spencer Stanhope.

The Grosvenor also hung works by women in its first exhibition and included them every year. Among the most well-known were: Sophie Anderson, Laura Alma-Tadema, Marie Spartali Stillman, Marianne Stokes, Louisa Starr Canzioni, Evelyn Pickering De Morgan, Louise Jopling, Anne Lea Merritt, Clara Montalba, Annie Louise Robinson Swynnerton, Princess Louise (Queen Victoria’s daughter), and Dorothy Tennant. Of 1028 artists shown in the fourteen years of gallery exhibitions, 25% were women, though they showed fewer works per artist than did their male cohorts and fewer works in the main East and West galleries (Newall 23-24).[3]

The Grosvenor welcomed watercolorists, a medium often slighted by the Academy, and works by artists who were considered new or avant-garde like Frank Holl, Elizabeth Armstrong Forbes and Stanhope Forbes, all associated with the Newlyn School of realist painters. Lindsay extended many invitations to foreign artists from America and the Continent: Giovanni Costa; Jules Bastien-Lepage, a French artist highlighted in 1880 and very influential on British art; Henri Fantin-Latour, much admired by Whistler; James Tissot (whom novelist/art critic Henry James disparaged in his review of the second Grosvenor exhibition); and Alphonse Legros, later art professor at the modernist Slade School of Art. Gustave Moreau exhibited L’Apparition, a very early Symbolist work, in 1877. A group of prominent Impressionists wrote to Lindsay to request a show at the Gallery: Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Auguste Renoir, Mary Cassatt, and Berthe Morisot, were among the signers. The exhibition never happened and it is possible that Lindsay did not know of them or of the importance of their works (Newall 24). Lindsay was especially fond of American and Canadian artists, as well as German, ![]() Austrian, Polish,

Austrian, Polish, ![]() Belgian, Dutch and Scandinavian artists who exhibited at the Grosvenor.

Belgian, Dutch and Scandinavian artists who exhibited at the Grosvenor.

The Grosvenor‘s total number of works exhibited over its lifetime was 5,091 (17% by women, Newall 24). Its summer exhibitions were of contemporary art, while its thirteen winter exhibitions from January to March, 1878-90, were varied: Old Masters, including drawings and extensive exhibitions of watercolors by deceased British artists and later by living ones (1238 by deceased artists in the first winter exhibition alone; Staley, 59). Gradually, winter exhibitions turned to drawings and watercolors by contemporary artists and some retrospectives: Watts in 1882; Alma-Tadema and others in 1883; Millais in 1886, and special exhibitions of Joshua Reynolds (1884), Thomas Gainsborough (1885), and Anthony Van Dyck (1887; see Staley, 60-61). In its last four years the Gallery also held autumn exhibitions, first of the work of Russian artist Vassili Verestchagin, then three autumn exhibitions devoted to works in pastel.[4]

Among the major contemporary paintings exhibited during the Grosvenor‘s existence were many by Burne-Jones, such as Laus Veneris (1878), The Golden Stairs (1880), The Wheel of Fortune (1883) and King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid (1884), and Whistler’s Miss Cicely Alexander (1881). Watts’s reputation flourished thanks to the Grosvenor exhibitions. He had been friends with Lindsay since the 1840s when they met in the rarified atmosphere of the artistic circles at Little Holland House. His Grosvenor paintings were also praised by Henry James who reviewed the second Grosvenor exhibition in 1878. The Grosvenor also highlighted new British art—British Impressionists of the New English Art Club (of which Whistler was a leader for a while), the Newlyn School painters and the ![]() Glasgow Boys (James Guthrie, John Lavery, among others)—praised by many critics, but also demeaned by others, including Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood co-founder and critic F. G. Stephens. James in 1878 criticized Whistler’s art as merely decorative “simple objects—as incidents of furniture or decoration,” but not acceptable as “pictures” (The Painter’s Eye, 12).

Glasgow Boys (James Guthrie, John Lavery, among others)—praised by many critics, but also demeaned by others, including Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood co-founder and critic F. G. Stephens. James in 1878 criticized Whistler’s art as merely decorative “simple objects—as incidents of furniture or decoration,” but not acceptable as “pictures” (The Painter’s Eye, 12).

The most problematic critic was, not surprisingly, John Ruskin, who admired Burne-Jones’s work in 1877, but attacked Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold (The Falling Rocket) in Letter 79 of Fors Clavigera so harshly that Whistler sued Ruskin for libel in what is considered a watershed case of Victorian aesthetic change (see Nicholas Frankel’s BRANCH entry, “On the Whistler-Ruskin Trial, 1878”). Burne-Jones and art critic Tom Taylor testified for Ruskin; Albert Moore, for Whistler. ![]() The painting most discussed at the trial was Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Old Battersea Bridge. Ruskin’s attack reflected a number of issues: the labor theory of value, including price; the nature of professionalism for artists; and the source of aesthetic authority—critic or artist. His attack marked a change in art criticism; critics formerly did not attack an artist, aware that such attacks could affect sales and artists’ incomes. Rather the practice was to ignore works they did not like, easily done in reviewing the hundreds of works exhibited at the RA.

The painting most discussed at the trial was Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Old Battersea Bridge. Ruskin’s attack reflected a number of issues: the labor theory of value, including price; the nature of professionalism for artists; and the source of aesthetic authority—critic or artist. His attack marked a change in art criticism; critics formerly did not attack an artist, aware that such attacks could affect sales and artists’ incomes. Rather the practice was to ignore works they did not like, easily done in reviewing the hundreds of works exhibited at the RA.

Ruskin’s comments were:

[f]or Mr. Whistler’s own sake, no less than for the protection of the purchaser, Sir Coutts Lindsay ought not to have admitted works into the gallery in which the ill-educated conceit of the artist so nearly approached the aspect of willful imposture. I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.

To Ruskin’s critique of the pricing for what appeared to be so little “work,” Whistler replied on the stand that he was asking 200 guineas not for the painting but for the artist’s skill at the end of the brush. Clearly, these two had different views about how to value a painting; Ruskin resorted to a labor theory of value, and Whistler was expressing a new professionalism among artists that defined pricing by skill level not labor hours, similar to the way pricing was set for doctors and lawyers. Although the final decision was in Whistler’s favor, he was awarded only one farthing without costs to pay his lawyer. Bankrupt after the trial, he was forced to sell his home and then went to Venice to do a series of commissioned etchings. Upon his return, he wrote a bitter commentary on the trial. Ruskin’s health declined dramatically after the trial.

The Grosvenor was the subject of much parody and satire: Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience, in which Reginald Bunthorne sings about “A greenery-yallery, Grosvenor Gallery,/Foot-in-the-grave young man!” satirized the entire Aesthetic Movement including the Gallery’s role within it. Francis Cowley Burnand’s play The Colonel also satirized the Grosvenor through a character based on Wilde and another character Basil Giorgione, who was portrayed as a stereotypical Grosvenor artist (think of Walter Pater’s admiration for Giorgione here, too). Both Aestheticism and the Grosvenor were repeatedly ridiculed in Punch as well, especially in cartoons by George du Maurier whose characters Mr. and Mrs. Cimabue Brown referred to the Pre-Raphaelites’ affection for 13th-and 14th-century Italian artists, such as Cimabue (1251-1302).

The operations of the Gallery were conducted by Charles Hallé, painter and son of the famous musician and his namesake, and Joseph Comyns Carr, who published articles promoting a radical reform of the RA. Coutts Lindsay did the majority of the art selection and was often besieged by artists wanting his attention and requesting studio visits and by professional organizations that feared the Grosvenor threatened their exhibitions and their publicity in the press.

In 1886 during the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London (see Aviva Briefel’s BRANCH entry, “On the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition”), several Australian colonies’ agents-general invited Coutts Lindsay to tour exhibitions in ![]() Australia, inspiring the Gallery to sponsor (but not organize) its one and only colonial exhibition, with 158 paintings by over 100 living artists held in

Australia, inspiring the Gallery to sponsor (but not organize) its one and only colonial exhibition, with 158 paintings by over 100 living artists held in ![]() Melbourne in 1887. This exhibition was praised by some critics for its education of public taste (Hewitt 595).

Melbourne in 1887. This exhibition was praised by some critics for its education of public taste (Hewitt 595).

The Lindsays separated in 1882. Coutts Lindsay’s Scottish farmlands were losing money and commercial enterprises within the Gallery, such as the restaurant, were not generating profits. He hired jeweler Joseph Pyke to come up with schemes to make money—a Clergy Club, circulating library, bookshop and dining room with an orchestra available for rent for private parties. Such measures appeared to some artists, like Burne-Jones, as denigrating the high art purpose of the Grosvenor. Struggling financially despite the success of a Millais exhibition in 1886, Lindsay sold his estate Balcarres to his cousin but had to close the gallery in 1890, because he owed £111,000 in debts.

In 1887, the Grosvenor Gallery suffered a crisis that began its decline. Prior to this time, Frederic Leighton had spent a great deal of time advocating for the RA among artists who might have sent works to the Grosvenor and to improving the RA’s reputation and public profile. In 1887, Burne-Jones, distressed at the new enterprises in the Gallery, wrote to Hallé that the Gallery was “losing caste” (Newhall 36). Hallé and Carr were also concerned at the direction the Gallery was taking and felt that Lindsay did not attend to their concerns. So, in November 1887, they published a letter in The Times and then resigned, creating the ![]() New Gallery off Regent Street (May 1888 opening-1909). They took many of the most signature artists with them, most notably Burne-Jones. This and Lindsay’s mounting debts led to the closing of the Grosvenor in 1890.

New Gallery off Regent Street (May 1888 opening-1909). They took many of the most signature artists with them, most notably Burne-Jones. This and Lindsay’s mounting debts led to the closing of the Grosvenor in 1890.

In analyzing the contributions of the Grosvenor, it is important to understand its place in the larger art world. This was a time when dealers were creating many new competing galleries and artists’ professional societies were emerging and exhibiting on behalf of their members after 1870; new notions of artistic professionalism and artists’ role in constructing national identity were emerging. This was a moment when debates raged about competition between amateur and professional artists (amateurs competed, often successfully, with professional artists in exhibitions and sales), women artists demanded recognition, overwhelming numbers of artists flooded the market (Huish) and artists insisted on professional status, identified with specialized skills and pricing that fit both demand and skills, rather than with the amount of time spent in the production of an art-work (Codell 2012). The Grosvenor and Whistler’s defense at the trial reflected not only artists’ struggles for a professional image, but also the promotion of a modernism distinct from what had become standard RA exhibition fare—an art that was popular, sentimental, realistic and narrative. The Grosvenor‘s exhibitions also contributed to an increasingly nationalistic discourse about the quality of British art, as well as to an expanding international interest in Continental, North American and “white” colony art. These national and international interests were reflected in articles in Britain’s art press and in the many dealers’ galleries in London specializing in foreign art exhibitions. Anticipating features of the modern art museum, such as shops, restaurants, and displays of works individually or grouped by artist, the Grosvenor‘s stamp of approval did much to raise the profile and reputation of British artists considered avant-garde. Once rejected by 20th-century modernists, Grosvenor artists, like Victorian artists in general, have enjoyed a steady climb in their reputations since the 1960s, and have been the focus of extensive scholarly attention, exhibitions, and publications in the last 20-30 years.[5]

published August 2014

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Codell, Julie. “On the Grosvener Gallery, 1877.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Blackburn, Henry. Grosvenor Notes, 1877-1885. London: Chatto and Windus, 1878-85. Print.

Carr, Joseph Comyns. Some Eminent Victorians. London: Duckworth, 1908. Print.

Casteras, Susan and Colleen Denney. The Grosvenor Gallery. New Haven: Yale UP, 1996. Print.

Codell, Julie. The Victorian Artist: Artists’ Life Writing in Britain. New York: Cambridge UP, 2003, pbk. rev. ed. 2012. Print.

Codell, Julie. “Artists’ Professional Societies: Production, Consumption and Aesthetics,” Towards a Modern Art World. Ed. B. Allen. London: Yale UP, 1995, 169-87. Print.

Codell, Julie. “The Cult of Aestheticism,” review of The Cult of Beauty, catalog and exhibition (San Francisco). Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies 22 (Fall 2013): 116-22. Print.

Denney, Colleen. “The Grosvenor Gallery as Palace of Art.” The Grosvenor Gallery. Eds. S. Casteras and C. Denney. New Haven: Yale UP, 1996. 9-36. Print.

Denney, Colleen. At the Temple of Art: The Grosvenor Gallery, 1877-1890. Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson UP/Associated UP, 2000. Print.

Freedman, Jonathan. Professions of Taste. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1990. Print.

“Grosvenor Gallery: The Worst Show for Many a Day.” New York Times 1888. 5. Print.

Glazer, Lee and Linda Merrill, eds. Palace of Art: Whistler and the Art Worlds of Aestheticism. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2013. Print.

Hallé, Charles. Notes on a Painter’s Life. London: John Murray, 1909. Print.

Hay, Mary Cecil. “The Grosvenor Gallery.” Art Journal, ns 6 (1880): 223-24. Print.

Hewitt, Martin, ed. The Victorian World. London: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Huish, Marcus B. “Whence This Great Multitude of Painters?” Nineteenth Century 32 (1892): 720-32. Print.

James, Henry. The Painter’s Eye. Ed. John L. Sweeney. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1989. Print.

Merrill, Linda. A Pot of Paint: Aesthetics on Trial in Whistler v. Ruskin. Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 1993. Print.

Newall, Christopher. The Grosvenor Gallery Exhibitions. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1995. Print.

Orr, Lynn Federle and Stephen Calloway, eds. The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic movement, 1860-1900. London: V&A Publishing, 2011. Print.

Stephenson, Andrew. “‘Anxious Performances’: Aestheticism, the Art Gallery and the Ambulatory Geographies of Late Nineteenth-Century London.” Secret Spaces, Forbidden Places: Rethinking Culture. Eds. Fran Lloyd and Catherine O’Brien. Oxford: Berghahn, 2001. 185-200. Print.

Surtees, Virginia. Coutts Lindsay, 1824-1913. Norwich: Michael Russell, 1993. Print.

Waterford, Giles. Palaces of Art. London: Dulwich Gallery and the National Gallery of Scotland, 1991. Print.

Wilde, Oscar, “The Grosvenor Gallery, 1877,” The Dublin Magazine, 90/535 (1877): 118-26. Print.

ENDNOTES

[1] See essays by Susan Casteras on Burne-Jones, John Siewert on Whistler, Barbara Bryant on G. F. Watts, and Kenneth McConkey on rustic naturalism in Casteras and Denney.

[2] See Paula Gillett’s chapter 2 on the Gallery’s audience in Casteras and Denney, 39-58.

[3] On the status of women artists as professionals, see Codell 1995, 2012; on women artists in the Grosvenor, their various styles and professional status, see Denney, 2000, especially Chapter 4, 127-50.

[4] See Allen Staley’s chapter 3 on the winter exhibitions in Casteras and Denney, 59-74.

[5] Along with recent books, catalogs and exhibitions on Aestheticism, the Grosvenor Gallery was the setting for a scene in Oliver Parker’s film adaptation of Wilde’s An Ideal Husband in 1999. I thank an anonymous reviewer of my entry for mentioning this.