Abstract

The event now known as “the voyage of the Beagle” comprises Charles Darwin’s circumnavigation as ship’s naturalist on the second of three surveying voyages by H.M.S. Beagle; the writings published as his first book, the Journal of Researches; and the genesis of his theory of evolution by natural selection. Writing between regimes of world-knowledge, Darwin mediates scientific observation through the language of aesthetics, and seeks to understand the convergence of disparate scales of geological and human history.

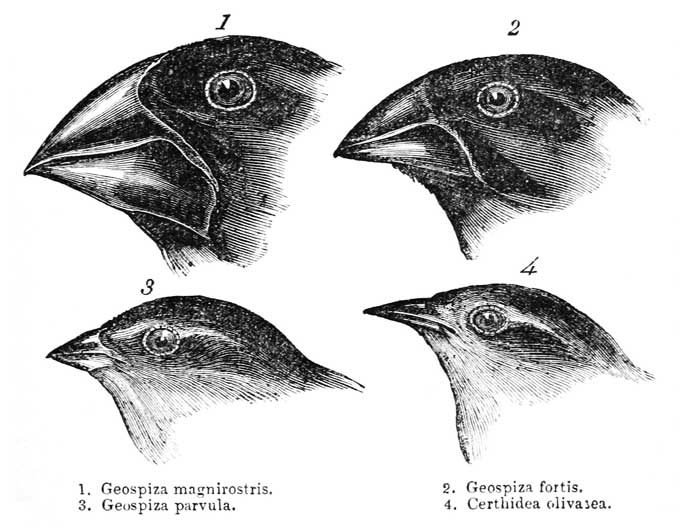

Figure 1: Diagram of H.M.S. Beagle (reproduced with permission from John van Wyhe ed., The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online)

Several different kinds, layers, and durations of event comprise the big event now known as “the voyage of the Beagle.” Charles Darwin’s five-year circumnavigation of the world as ship’s naturalist took place on the second of three long-range surveying voyages carried out by the Royal Navy brig H.M.S. Beagle (see Fig. 1). The first two voyages, furthering the chronometric and hydrographic survey of the globe, corrected measurements of longitude and charted the southern coasts of South America. On the first voyage, 1826-1830, the Beagle accompanied H.M.S. Adventure to ![]() Patagonia and

Patagonia and ![]() Tierra del Fuego under the command of Philip Parker King. Robert FitzRoy captained the second, solo voyage, 1831-1836, on which Darwin was a passenger. The Beagle went out a third time to survey the coasts of

Tierra del Fuego under the command of Philip Parker King. Robert FitzRoy captained the second, solo voyage, 1831-1836, on which Darwin was a passenger. The Beagle went out a third time to survey the coasts of ![]() Australia in 1837-1843, under John Clement Wickham and John Lort Stokes, before retirement to coastguard duty (1845) as a floating customs and excise base on the

Australia in 1837-1843, under John Clement Wickham and John Lort Stokes, before retirement to coastguard duty (1845) as a floating customs and excise base on the ![]() Essex marshes.

Essex marshes.

Darwin’s presence on board the Beagle was supplementary if not ornamental to the official aims of the second voyage, which were to provide accurate charts for naval, commercial, and colonial navigation and to stake a British strategic claim around the shores of South America following the breakup of the Spanish and Portuguese empires. The aristocratic Captain FitzRoy (nephew of the fourth Duke of Grafton and the third Marquis of Londonderry) sought someone who would be an acceptable table companion as well as a competent geologist. After several other candidates were canvassed, John Stevens Henslow, Professor of Botany at the ![]() University of Cambridge, recommended his twenty-two-year-old former student Darwin, who came on board as a gentleman amateur, his equipment and expenses paid for by his father. Darwin’s informal, unaffiliated role as ship’s naturalist made his case very different from that of Enlightenment grandee manager-patrons like botanist Joseph Banks, who held an Admiralty appointment on the first Cook voyage and devoted his own resources to hiring a team of skilled collaborators; it also set him apart from the professional scientists of modern expeditions. His private status gave him a great deal of autonomy over his time and activity, as well as his collections, while his fellowship with the captain allowed him to take advantage of the expedition’s resources to ship his specimens back to England. Early on, he became a stumbling block to the ship’s surgeon, Robert McCormick, who felt entitled to assume the role of naturalist (as was his customary right) in the absence of official instructions appointing Darwin. McCormick left the Beagle in high dudgeon four months after it set out, his professional ambition overridden by the well-connected gentleman passenger (Browne 202-210).

University of Cambridge, recommended his twenty-two-year-old former student Darwin, who came on board as a gentleman amateur, his equipment and expenses paid for by his father. Darwin’s informal, unaffiliated role as ship’s naturalist made his case very different from that of Enlightenment grandee manager-patrons like botanist Joseph Banks, who held an Admiralty appointment on the first Cook voyage and devoted his own resources to hiring a team of skilled collaborators; it also set him apart from the professional scientists of modern expeditions. His private status gave him a great deal of autonomy over his time and activity, as well as his collections, while his fellowship with the captain allowed him to take advantage of the expedition’s resources to ship his specimens back to England. Early on, he became a stumbling block to the ship’s surgeon, Robert McCormick, who felt entitled to assume the role of naturalist (as was his customary right) in the absence of official instructions appointing Darwin. McCormick left the Beagle in high dudgeon four months after it set out, his professional ambition overridden by the well-connected gentleman passenger (Browne 202-210).

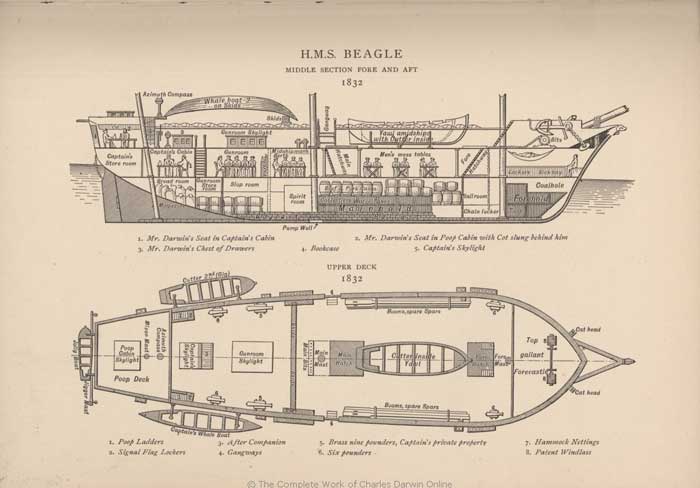

Figure 2: Map of the circumnavigation of H.M.S. Beagle (reproduced with permission from John van Wyhe ed., The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online)

Darwin’s voyage officially began in October 1831, when he joined the Beagle at ![]() Plymouth (see Fig. 2); departure was delayed, however, by adverse winds, and the ship did not leave England until 27 December. During the first year of the voyage, the Beagle sailed southward along the Atlantic coast of South America, from

Plymouth (see Fig. 2); departure was delayed, however, by adverse winds, and the ship did not leave England until 27 December. During the first year of the voyage, the Beagle sailed southward along the Atlantic coast of South America, from ![]() Bahia to Tierra del Fuego. It spent 1833-34 shuttling between Tierra del Fuego,

Bahia to Tierra del Fuego. It spent 1833-34 shuttling between Tierra del Fuego, ![]() the Falkland Islands, and the continental southern Atlantic coast before threading the

the Falkland Islands, and the continental southern Atlantic coast before threading the ![]() Straits of Magellan into the Pacific in June 1834. Throughout the remainder of 1834 and much of 1835 it surveyed the western coasts of South America and outlying islands, heading to the

Straits of Magellan into the Pacific in June 1834. Throughout the remainder of 1834 and much of 1835 it surveyed the western coasts of South America and outlying islands, heading to the ![]() Galápagos archipelago in September 1835. The following year, the Beagle traversed Australasia and the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, returning (via Bahia again) to England in October 1836. Darwin never got over being seasick and disliked being cooped up on the ship. In the course of the voyage, he spent nearly twice as much time on inland expeditions—exploring the Brazilian rainforest, riding with gauchos on the

Galápagos archipelago in September 1835. The following year, the Beagle traversed Australasia and the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, returning (via Bahia again) to England in October 1836. Darwin never got over being seasick and disliked being cooped up on the ship. In the course of the voyage, he spent nearly twice as much time on inland expeditions—exploring the Brazilian rainforest, riding with gauchos on the ![]() pampas, crossing the

pampas, crossing the ![]() Andes—as he did on board.

Andes—as he did on board.

As well as the five-year-long circumnavigation, “the Voyage of the Beagle” designates a literary event: the appearance of Darwin’s first book, his journal of the expedition, in June 1839. It only gradually acquired that title. Journal and Remarks, 1831-1836, by Charles Darwin, Esq., M.A. was the third volume, following the official proceedings by commanders King and FitzRoy, in a three-volume set (plus an appendix to volume 2) edited by FitzRoy and published by Henry Colburn, entitled The Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of H.M. Ships Adventure and Beagle, between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their Examination of the Southern Shores of South America, and the Beagle’s Circumnavigation of the Globe. Colburn reprinted Darwin’s volume as a single book (also in 1839) with the title Journal of Researches into the Geology and Natural History of the Various Countries visited by H.M.S. Beagle, under the Command of Captain FitzRoy, R.N., from 1831 to 1836. The voyage narratives were accompanied by a flight of more specialist works: the lavish, government-subsidized Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, written by established experts and edited by Darwin, published in five volumes between 1838 and 1843; and the three-volume companion Geology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, written by Darwin himself, 1842-1846.

The emergence of the Journal of Researches as a discrete book tracks Darwin’s increasing visibility as an author and naturalist in the early decades of his career. He revised the work for a second edition, issued in 1845 in three monthly parts by John Murray (who would become Darwin’s regular publisher) in a cheap popular series, The Colonial and Home Library; the spine of the book issue condenses the title to Naturalist’s Voyage (in later editions, Naturalist’s Voyage Round the World). The 1845 edition differs significantly from the edition of 1839. Darwin condensed the text and rationalized its order, re-organizing the chapters to follow the geographical course of the circumnavigation rather than its chronology, so that multiple visits to a single location (e.g., Tierra del Fuego, December 1832-February 1833, February 1834, June 1834) are corralled into a single chapter or continuous narrative unit. Darwin also expanded and enhanced his general natural historical reflections, incorporating some of his developing research on the species question. This version—reissued in 1860 with a brief postscript correcting some of the scientific data—established the text of The Voyage of the Beagle (as the work was rechristened in 1905) as it has been reprinted and read ever since. Remarkably, there has been no complete scholarly edition, either of the 1839 or of the 1845 versions, of so famous and consequential a work.

Darwin based the published Journal of Researches on the detailed diary and field notes he kept during the voyage. He wrote up his diary entries on board ship, days and in some cases even weeks after the events recorded, drawing on the notes he made during his land expeditions. (Darwin’s notebooks as well as the Beagle Diary—edited by R. D. Keynes for Cambridge University Press, 1988—can be consulted at the Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online, edited by John van Wyhe.) A third textual stratum of the voyage consists of the letters Darwin wrote home to his family, friends, mentors and a widening circle of scientific correspondents. Frederick Burkhardt has edited a handsome one-volume collection of The Beagle Letters, including replies from Darwin’s correspondents (Cambridge, 2008), drawn from the ongoing Collected Letters of Charles Darwin (most of which are also accessible online at the Darwin Correspondence Project). Anyone interested in the voyage, in short, has ready access to a remarkably rich archive of primary as well as published documents.

The third event designated by “the voyage of the Beagle” is at once personal and world-historical—or, in other words, mythic. Through the voyage, Darwin became Darwin; it was the origin of the Origin of Species. “The voyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life & has determined my whole career,” Darwin wrote in the autobiography he compiled for his family near the end of his life; “the shape of his head is quite altered,” he records his father as commenting on his return (“Recollections” 387-388). It was the shape of the world. From a callow scion of midlands gentry, drifting half-heartedly towards a country parsonage, like a minor character in a Jane Austen novel (Darwin’s correspondence with his sisters casts him as the feckless Dick Musgrove, from Persuasion, and FitzRoy as the dashing Captain Wentworth: The Beagle Letters 54, 205), he would become the most celebrated thinker of the nineteenth century, the author of its major scientific revolution. In July 1837, in the midst of revising his Beagle manuscripts for the Journal of Researches, Darwin opened the first of a series of notebooks on the transmutation of species, which he would spend the next couple of decades refining into “the theory of descent with modification through natural selection” (Origin 338).

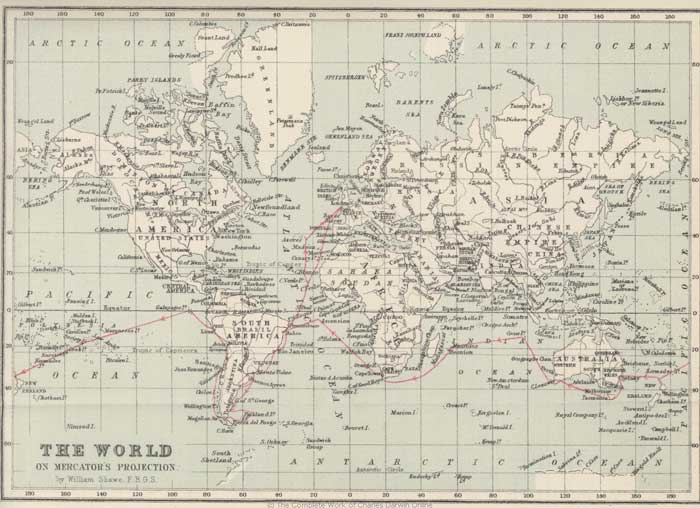

The voyage became the crucible of the theory well after it was over. It trained Darwin’s powers of observation and reasoning, as he acknowledged (a ten-gun brig was his true Cambridge), and it afforded a vast fund of empirical data he would draw on in the development of his “one long argument” (Origin 338): peculiarities in the geographical distribution of plant and animal populations, fossil evidence of species extinction, geological traces of the mutability of continents. The mythic scenario of Darwin on the Beagle is set in the Galápagos, where the diversification of closely related populations of birds and tortoises across the islands made the archipelago a laboratory for the transmutation of species. Its icon is the famous illustration of the beaks of Galápagos finches, printed in the second edition (1845) of the Journal of Researches. (See Fig. 3.) However, no flash of revelation came to Darwin on the islands. He does not mention the potential evidence of intermediate links in a process of speciation in his diary. Nor, as Frank J. Sulloway has shown, did the finches play a particularly important part in the development of Darwin’s theory. In his field notes, written up shortly after leaving the Galápagos in October 1835, Darwin comments on the “difficulty in ascertaining the species” of the islands’ dusky-plumaged small birds (Zoology Notes 297); nine months later (July 1836) he refers to the “gradation in the form of the bill” as one element of their “inextricable confusion” (qtd. in Barlow 261). In his published journal, Darwin confessed he did not have the leisure to think of systematically collecting specimens from the different islands, or even sorting the ones he took.

It was while looking back at his notes on the Galápagos mocking-birds, in July 1836, that realization began to grip:

When I see these Islands in sight of each other, & [but del.] possessed of but a scanty stock of animals, tenanted by these birds, but slightly differing in structure & filling the same place in Nature, I must suspect they are only varieties. . . . If there is the slightest foundation for these remarks the zoology of Archipelagoes—will be well worth examining; for such facts [would] undermine the stability of Species. (qtd. in Barlow 262)

A year later, his first species notebook (Notebook “B,” July 1837) develops the thought: “According to this view animals, on separate islands, ought to become different if kept long enough.—<<apart, with slightly differen [sic] circumstances” (Charles Darwin’s Notebooks 172). In March 1837, John Gould, analyzing Darwin’s specimens for the ornithology volume of Zoology of the Beagle, had broken the news that the small birds from the Galápagos were all different but closely related species of finch. “It is very remarkable that a nearly perfect gradation of structure in this one group can be traced in the form of the beak, from one exceeding in dimensions that of the largest gros-beak, to another differing but little from that of a warbler,” Darwin wrote in the published Journal of Researches (1839: 462). In the second edition, by now well advanced on his species research, he went further: “Seeing the gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends” (1845: 380). And he added: “it is the circumstance, that several of the islands possess their own species of the tortoise, mocking-thrush, finches, and numerous plants, these species having the same general habits, occupying analogous situations, and obviously filling the same place in the natural economy of this archipelago, that strikes me with wonder” (397)—ten years after he had set foot there.

2.

In October 1836, a few days away from England, Darwin wrote up “a short retrospect of the advantages and disadvantages, the pains and pleasures, of our five years’ wandering” (Journal of Researches 1839: 602). He reflects on the voyage as a historical event as well as an autobiographical one. “The short space of sixty years has made an astonishing difference in the facility of distant navigation” (602): technological progress and the spread of colonies have largely removed the privations encountered during the voyages of Cook. The reflection yields a patriotic high note:

From seeing the present state, it is impossible not to look forward with high expectations to the future progress of nearly an entire hemisphere. The march of improvement, consequent on the introduction of Christianity throughout the South Sea, probably stands by itself in the records of history. It is the more striking when we remember that only sixty years since, Cook, whose excellent judgment none will dispute, could foresee no prospect of a change. (607)

Darwin’s emphasis on the passage of sixty years between his own and James Cook’s voyages (1768-1780) echoes the famous retrospect that closes Walter Scott’s historical novel Waverley, or ‘Tis Sixty Years Since: “There is no European nation which, within the course of half a century, or little more, has undergone so complete a change as this kingdom of ![]() Scotland. . . . The gradual influx of wealth, and extension of commerce, have since united to render the present people of Scotland a class of beings as different from their grandfathers as the existing English are from those of Queen Elizabeth’s time” (340). Like the author of Waverley, Darwin looks back to a primitive age, an age of adventure, which has fallen definitively into the past. “Sixty years since” marks a period, a horizon at which the past becomes visible as the past—and at which the present also acquires historical gravity, as the modern condition from which we are looking back. Darwin’s echo of Scott acknowledges his place in literary history as well as in the histories of science and exploration. In the remainder of this essay, I offer some considerations on the voyage of the Beagle as a literary event—an event in the history of representation.

Scotland. . . . The gradual influx of wealth, and extension of commerce, have since united to render the present people of Scotland a class of beings as different from their grandfathers as the existing English are from those of Queen Elizabeth’s time” (340). Like the author of Waverley, Darwin looks back to a primitive age, an age of adventure, which has fallen definitively into the past. “Sixty years since” marks a period, a horizon at which the past becomes visible as the past—and at which the present also acquires historical gravity, as the modern condition from which we are looking back. Darwin’s echo of Scott acknowledges his place in literary history as well as in the histories of science and exploration. In the remainder of this essay, I offer some considerations on the voyage of the Beagle as a literary event—an event in the history of representation.

The Cook expeditions, completing the map of the world’s coastlines, had turned the planet into a closed cartographical system, fully available for European projects of knowledge and exploitation. Darwin’s discovery—fructifying a quarter-century later—would confirm the voyage of the Beagle as the last episode in an Enlightenment tradition of circumnavigation, “a double deed that consists of sailing round the world then writing an account of it” (Pratt 29). Its openness to an encyclopedic variety of topics and discourses had made travel writing one of the major literary genres of the long eighteenth century; the journal of a voyage could accommodate philosophical observations of different lands and peoples (comprising “the world”) as well as the subjective account of its author’s experiences, sensations, and reflections. Darwin downplays his subjective presence, even in the diary, but his position and function—as observer, as participant, as author—are crucial to the narrative’s unfolding. Scientifically, he attends to the controversial phenomena of human history as well as the ramifying branches of natural history. Along with the geographical ranges of flora and fauna, the formation of geological strata and coral reefs, he observes the decline and growth of colonial empires and intervenes in contemporary debates on slavery, the impact of missionaries, and the status and fate of “savages.” His planetary circuit registers the contemporary breakup and recombination of those meta-disciplinary themes of Enlightenment, the history of the world and the science of man, under the stress of new thought: the natural history of man, radically reimagined by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck in his Philosophie zoologique (1809; reissued 1830), and the history of the earth, recast by Charles Lyell in Principles of Geology (1830-1833). Darwin embraced Lyell’s geological argument, which he read during the voyage (along with Milton’s Paradise Lost) as the successive volumes were published; Lyell’s refutation of Lamarck’s transmutationist hypothesis in the second volume of Principles, meanwhile, ensured its continuing, scandalous visibility.

The book Darwin mentions most often, especially during the first year of the voyage, is Alexander von Humboldt’s Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent in the Years 1799-1804, several volumes of which (in Helen Maria Williams’s translation) he took with him. As Darwin later wrote, “my whole course of life is due to having read and reread as a Youth the Personal Narrative” (Correspondence 3: 140). Humboldt inspired Darwin with the desire to visit the tropics, and his synthesis of memoir and scientific survey provided a model of literary technique as well as of “professional self-fashioning” (Leask 16, 20, 33; see also Richards 514-25; Sloan 24-25, 33-35). In the introduction to the Personal Narrative, Humboldt acknowledges the scientific value of travel writing but criticizes the pre-disciplinary shortcomings of its practitioners, who failed to keep pace with advances in the natural sciences, and the limitations of “maritime expeditions [and] voyages round the world,” as “less fitted to advance the progress of geology, and other parts of general physics, than travels into the interior of a continent” (1: vi-vii). He calls for a new science, “of which we as yet possess scarcely the outline, and which has been vaguely denominated natural history of the world, theory of the Earth, or physical geography” (iii).

As well as giving Darwin license for his inland expeditions during the voyage of the Beagle, Humboldt’s remarks would have helped bring into focus his historical situation, setting sail after the heroic age of exploration but before a new kind of world-knowledge has taken shape. That historical interim—the sense of living and thinking between epistemes—is the condition for Darwin’s as well as Humboldt’s Romanticism (and perhaps it may be understood as a condition for what we call “Romanticism”). “The limit of man’s knowledge in any subject possesses a high interest, which is perhaps increased by its close neighborhood to the realms of imagination,” Darwin wrote in the Journal of Researches (1839: 345). “Darwin’s questions seem to exist in the space between other, prior categories of aesthetic and scientific response,” comments Richard Stein; “they suggest the transformation of imaginative insights into scientific discourse, into a new mode of discourse being created while the questions are being asked” (214). And George Levine characterizes “the double movement” of Darwin’s prose, in which the initial sense of wonder at a natural phenomenon is enhanced, not dispelled, by the provision of a rational explanation for it (60-71). The “rare union of poetry with science” (Charles Darwin’s Beagle Diary 42) Darwin found in Humboldt’s descriptions of the South American rainforest prepared him for scientific discovery as an aesthetic experience:

As the force of impressions generally depends on preconceived ideas, I may add, that all mine were taken from the vivid descriptions in the Personal Narrative of Humboldt, which far exceed in merit any thing I have read on the subject. Yet with these high-wrought ideas, my feelings were far from partaking of any tinge of disappointment on first landing on the shores of

Brazil. (Journal of Researches 1839: 604)

Humboldt’s writings, shaping Darwin’s ideas in advance, intensified rather than dulled his response to the actual scenery. “The mind is a chaos of delight, out of which a world of future & more quiet pleasure will arise. — I am at present fit only to read Humboldt; he like another Sun illumines everything I behold” (Charles Darwin’s Beagle Diary 42). Even in the blaze of his first excitement Darwin recognizes a mediated, temporally extensive, typically Romantic structure of aesthetic experience. The “chaos of delight” that attends the act of observation, trained by prior reading, supplies a store of impressions for later, calmer recollection. This structure of aesthetic experience will also constitute the structure of scientific discovery, in which recollection in tranquility (compare Wordsworth 611) entails the analysis and ordering of the data of observation into a coherent system—as in the gradual emergence of the meaning of Darwin’s observations on the Galápagos, months and even years after the event.

3.

The terms in which Darwin seeks to reckon the “advantages and disadvantages . . . of our five years’ wandering” are thus, strikingly, aesthetic terms: pain and pleasure, the beautiful and the sublime. Darwin signals his private status, his freedom from the voyage’s official aims, with this aesthetic register; at the same time, his engagement with it is intellectually serious. He contrasts “the picturesque beauty of many parts of Europe” with the wild regions of the earth:

Among the scenes which are deeply impressed on my mind, none exceed in sublimity the primeval forests undefaced by the hand of man; whether those of Brazil, where the powers of Life are predominant, or those of Tierra del Fuego, where Death and Decay prevail. (Journal of Researches 1839: 604)

Darwin develops Edmund Burke’s celebrated distinction between the sublime and the beautiful to identify, instead, different modes of the sublime: what we might call a beautiful sublime, associated with “the powers of Life,” and its antithesis, associated with “Death and Decay.” These aesthetic modes correspond with the visions of the earth prepared for Darwin by Humboldt and Lyell, and to that extent they chart the development of his thinking during the voyage.

An ecstatic overload of sensory impressions characterizes the Humboldtian sublime:

I believe from what I have seen Humboldts [sic] glorious descriptions are & will for ever be unparalleled: but even he with his dark blue skies & the rare union of poetry with science which he so strongly displays when writing on tropical scenery, with all this falls far short of the truth. The delight one experiences in such times bewilders the mind,—if the eye attempts to follow the flight of a gaudy butter-fly, it is arrested by some strange tree or fruit; if watching an insect one forgets it in the stranger flower it is crawling over,—if turning to admire the splendour of the scenery, the individual character of the foreground fixes the attention. The mind is a chaos of delight . . . . (Charles Darwin’s Beagle Diary 42)

In a new epiphany of the world, the imagination opens onto the plenitude of life itself as a dynamic totality of organic relations: “Well may we affirm that every part of the world is habitable! Whether lakes of brine, or those subterranean ones hidden beneath volcanic mountains—warm mineral springs; the wide expanse and depths of the ocean; the upper regions of the atmosphere; and even the surface of perpetual snow;—all support organic beings” (Journal and Remarks 77). Darwin apprehends the earth as a ‘cosmos’ (Humboldt’s term; Richards 520-521) or biosphere (to use a phrase coined in his lifetime, by the geologist Eduard Suess), a complex homeostasis of living systems (see Krasner; Leask 16-22; Paradis).

The other mode of the sublime is absolute, uncompromised by beauty—the sublime of “Death and Decay.” It attends a privation rather than repletion of the senses. Its temporal structure is one of uncanny recurrence—haunting—rather than instantaneous rapture. But its hold is no less compelling:

In calling up images of the past, I find the plains of Patagonia frequently cross before my eyes: yet these plains are pronounced by all most wretched and useless. They are characterized only by negative possessions; without habitations, without water, without trees, without mountains, they support merely a few dwarf plants. Why then, and the case is not peculiar to myself, have these arid wastes taken so firm possession of the memory? . . . I can scarcely analyze these feelings: but it must be partly owing to the free scope given to the imagination. (Journal of Researches 1839: 605)

Darwin articulates a recognizably Romantic structure of the sublime, more akin to Kant or (still more) to Wordsworth—“I can scarcely analyze these feelings”—than to Burke. Its full effect is felt at a temporal distance from the event, in memory and reflection. Instead of being overwhelmed by a joyous excess of sensory stimuli, the observer finds his imagination haunted by a ghostly insistence of what he calls “negative possessions”—“without habitations, without water, without trees, without mountains,” “most wretched and useless.” Darwin strives to articulate a strange aesthetic enjoyment arising from this emptiness. Here Darwin’s Romanticism—his situation in a literary and aesthetic as well as a scientific history—tells the difference between his account and the accounts of travelers who sailed during the heroic age of circumnavigation, when the map of the world was still open, its horizons as yet unbounded: subject, in Jonathan Lamb’s account, to terrifying psychosomatic calentures, to body- and soul-destroying attacks of panic and scurvy (121-128). Darwin’s Beagle writings are notable for the absence of this kind of existential vertigo on the far side of the world. Instead, the closure of the world makes it possible for Darwin to claim access to a superior aesthetic enjoyment through the apprehension of “negative possessions,” in the form of a freedom of the imagination: “I can scarcely analyze these feelings: but it must be partly owing to the free scope given to the imagination.”

Darwin puts that freedom to work. The “free scope” opened for the imagination becomes the enhanced cognitive range required to apprehend the vastly enlarged dimensions—the “deep time”—of Lyell’s new earth history. “The plains of Patagonia bear the stamp of having thus lasted for ages, and there appears no limit to their duration through future time” (Journal of Researches 1839: 605). This part of the “retrospect” glosses Darwin’s journal entry of 28 December 1833:

All was stillness and desolation. One reflected how many ages the plain had thus lasted, and how many more it was doomed thus to continue. Yet in passing over these scenes, without one bright object near, an ill-defined but strong sense of pleasure is vividly excited. (198)

In the 1845 edition of the Journal of Researches, Darwin inserts lines from Shelley’s ![]() Mont Blanc:

Mont Blanc:

None can reply—all seems eternal now.

The wilderness has a mysterious tongue

Which teaches awful doubt. (168)

The citation from one of the sublime masterpieces of English poetry reinforces the heightened pedagogical emphasis of the second edition, in which Darwin makes a programmatic attempt to harness “awful doubt” as a cognitive aid to Lyellian geohistory. There lingers, nevertheless, a temporal as well as a rhetorical gap between the pedagogical theme and the tentative, veiled, troubling quality of the “pleasure” that Darwin recognizes.

Summarizing his analysis of Patagonian tertiary formations in the 1839 edition, Darwin comments in 1845:

When we consider that all these pebbles, countless as the grains of sand in the desert, have been derived from the slow falling of masses of rock on the old coast-lines and banks of rivers; and that these fragments have been dashed into smaller pieces, and that each of them has since been slowly rolled, rounded, and far transported, the mind is stupified in thinking over the long, absolutely necessary, lapse of years. (171)

Darwin rationalizes and domesticates the sublime by calibrating it to the gradualist scale of everyday life: removing, in so doing, its catastrophic threat. The minute-by-minute, microscopic accretion of phenomena piles up across the overwhelming magnitudes of geological time, raising mountain ranges, shearing continents.

Later, Darwin listens to the white noise of the Andean river ![]() Maipu, caused by the friction of pebbles swept along by the flood:

Maipu, caused by the friction of pebbles swept along by the flood:

It is not possible for the mind to comprehend, except by a slow process, any effect which is produced by a cause repeated so often, that the multiplier itself ceases to convey any more definite idea, than the savage receives when he points to the hairs of his head. . . . [W]hen listening to the rattling noise of these torrents, and calling to mind that whole races of animals have passed away from the surface of the globe, during the period throughout which, night and day, these stones have gone rattling onwards in their course, I have thought to myself, can any mountains, any continent, withstand such waste? (1839: 385-6)

The “savage” makes a rhetorical appearance as at once the antitype to rational computation, and thus scientific knowledge, and as a type of the observer—Darwin himself—striving to reassert cognitive mastery in the face of an abysmal infinitude. Where the savage may fail, Darwin must succeed, since the savage also indexes the historical coordinates of this geological meditation in the scales of the life sciences and human history: the extinction of animal species, which Darwin mentions, and the extinction of human populations, which he does not—but for which the baffled savage stands in.

These passages open onto a disjunction between different timescales, that of geological history and that of everyday human life, which is so enormous as to make them seem incommensurable. On a terrestrial scale, Darwin commits his thinking to a Lyellian history of gradual, incremental transformations over vast extents of time. According to Lyell, “the elevating and depressing power of earthquakes, which visits, in succession, every zone, and fills the earth with monuments of ruin and disorder, is, nevertheless, a conservative principle in the highest degree, and, above all others, essential to the stability of the system” (178-179). The difference between human history and earth history is so tremendous as almost to set them in separate dimensions—“ruin and disorder,” a tragic phenomenology of experience, versus “the stability of the system,” a serene homeostasis.

Darwin’s journal, by virtue of its being a day-to-day record of experience and observation, records an exceptional convergence of the scales of geological, national, and personal history. The great Chilean earthquake of February 1835 (see Fig. 4) affords him an opportunity to observe the metamorphosis of the earth’s crust, a process that normally unfolds over millennia, concentrated into mere minutes—into a historical event. This produces a representational crisis—a breakdown of the relation between language, knowledge and feeling:

Figure 4: Remains of the Cathedral of Concepcion after the 1835 earthquake, sketched by John Clemens Wickham, 1839 (reproduced with permission from John van Wyhe ed., The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online)

I have not attempted to give any detailed description of the appearance of

Concepcion, for I feel it is quite impossible to convey the mingled feelings with which one beholds such a spectacle. Several of the officers visited it before me, but their strongest language failed to communicate a just idea of the desolation. It is a bitter and humiliating thing to see works, which have cost men so much time and labour, overthrown in one minute; yet compassion for the inhabitants is almost instantly forgotten, from the interest excited in finding that state of things produced in a moment of time, which one is accustomed to attribute to a succession of ages. In my opinion, we have scarcely beheld since leaving England, any other sight so deeply interesting. (Journal of Researches 1839: 376-7)

The observer’s perturbation and bafflement arise from the collision between states of feeling attached to the different scales of geological and human history. To the geologist, the spectacle of “that state of things produced in a moment of time, which one is accustomed to attribute to a succession of ages,” must be “deeply interesting.” But scientific interest clashes with the pathos of the scene’s human content—the “bitter and humiliating” sight of civilization overthrown, “compassion for the inhabitants.” Again, Darwin rehearses the structure of the Romantic sublime, in which cognitive or imaginative overthrow opens onto a larger range of “interest.” This time, however, the process occupies the scale of human history, and carries with it pathetic and ethical disturbances that are harder to resolve: at least, not without a renunciation of human feeling altogether.

4.

Death—mass death, the destruction of populations—is the prospect that opens here, and it forms an ethical crux in Darwin’s thinking. Darwin finds the evidence of species extinctions, crucial data in the Lyellian theory of the earth, scattered across the sedimentary deposits of South America—the Argentine Pampas is “one wide sepulchre for . . . extinct quadrupeds” (Journal of Researches 1839: 155). Darwin argues that extinction occurs gradually, with members of a population dwindling by units over many generations, rather than perishing in an instantaneous crash. Extinction, in other words, is not so much an event—a historical phenomenon—as it is a process—a natural phenomenon:

To admit that species generally become rare before they become extinct—to feel no surprise at the comparative rarity of one species with another, and yet to call in some extraordinary agent and to marvel greatly when a species ceases to exist, appears to me much the same as to admit that sickness in the individual is the prelude to death—to feel no surprise at sickness—but when the sick man dies, to wonder, and to believe that he died through violence. (1845: 176)

Darwin was fond enough of this reflection, inserted in the 1845 edition of the Journal, to repeat it in the Origin of Species (235). The analogy with human fatalities through sickness and violence is suggestive, since the politically organized elimination of human populations is one of the phenomena Darwin observes in the course of his voyage. He witnesses General Juan Manuel de Rosas’ campaign to exterminate the Pampas Indians in 1833, and he makes landfall at ![]() Van Diemen’s Land in 1836, three years after the removal of the island’s aborigines. While he is able to represent the earthquake as an exceptional intrusion of natural forces into human history, and thus to articulate its catastrophic violence in terms of a collision of scales, here Darwin finds himself viewing extinction as an event that happens fully inside human history—the world history of European colonization that his circumnavigation advances.

Van Diemen’s Land in 1836, three years after the removal of the island’s aborigines. While he is able to represent the earthquake as an exceptional intrusion of natural forces into human history, and thus to articulate its catastrophic violence in terms of a collision of scales, here Darwin finds himself viewing extinction as an event that happens fully inside human history—the world history of European colonization that his circumnavigation advances.

Riding on the fringes of Rosas’ campaign, Darwin understands himself as visiting a barbaric stage of historical development, analogous to the European Middle Ages. (Rosas is a picturesque warlord out of Scott.) The relation of historical distance allows Darwin a set of modulated responses to the campaign, including a cool acceptance of the inevitability if not necessity of the genocide, horror at reported atrocities, and even a regret at the vanishing of the wild savages. That regret assumes an aesthetic, self-consciously “romantic” mode, as in the story Darwin tells of an Indian chief’s escape with his son from Rosas’ troops: “What a fine picture one can form in one’s mind,—the naked, bronze-like figure of the old man with his little boy, riding like a Mazeppa on the white horse, thus leaving far behind him the host of his pursuers!” (Journal of Researches 1839: 104-105). The Indians’ imminent extinction is the historical condition that frames the “fine picture” (modeled, not altogether appropriately, on the poem by Byron) and makes it available for contemplation. (See Fig. 5.)

Figure 5 (top left): Mazeppa, by Eugène Delacroix (1828); Figure 6 (right): Mazeppa, by Théodore Géricault (1823); Figure 7 (bottom left): Mazeppa, by Horace Vernet (1826)

Darwin’s responses become more troubled as he moves away from the former Spanish and Portuguese empires into the range of the new British settlements in the South Pacific. He observes dejected bands of aborigines straggling across the Australian colony:

Wherever the European has trod, death seems to pursue the aboriginal. We may look to the wide extent of the Americas,

Polynesia,

the Cape of Good Hope, and Australia, and we find the same result. . . . The varieties of man seem to act on each other in the same way as different species of animals—the stronger always extirpating the weaker. It was melancholy in

New Zealand to hear the fine energetic natives saying, that they knew the land was doomed to pass from their children. (1839: 520)

Darwin rehearses what Patrick Brantlinger has called “extinction discourse,” a pseudo-analysis that naturalizes the disappearance of native peoples, once European settlement has begun, as a mysterious, maybe regrettable, in any case inevitable process (164-170). However, Darwin’s reflections on human extinction, taken together, are rather more complex and vexed than the passage just quoted might suggest.

Occupying a position at the nethermost margin of what Burke had called “the great map of mankind,” the savage is a key figure in the Enlightenment discourse of universal history. He is a figure of human origins and ends, of the murky borders between nature and culture and between animal and man, and also of the extreme ethical consequences of the imperial mission: a historical event that will issue in his salvation (Christian conversion, assimilation into civilization) or his destruction. For Darwin, as for earlier voyagers, it was the inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego, the Haush and Yamana peoples, who exemplified “man in his lowest and most savage state”:

Of individual objects, perhaps no one is more certain to create astonishment than the first sight in his native haunt of a real barbarian,—of man in his lowest and most savage state. One’s mind hurries back over past centuries, and then asks, could our progenitors have been such as these? Men, whose very signs and expressions are less intelligible to us than those of the domesticated animals; men, who do not possess the instinct of those animals, nor yet appear to boast of human reason, or at least of arts consequent on that reason. I do not believe it is possible to describe or paint the difference between savage and civilized man. (Journal of Researches 1839: 605-606)

This passage from the “short retrospect” reiterates Darwin’s Diary account of his first encounter with the native Fuegians:

It was without exception the most curious & interesting spectacle I ever beheld. —I would not have believed how entire the difference between savage & civilized man is. —It is greater than between a wild & domesticated animal, in as much as in man there is greater power of improvement. (265)

We hear dissonant echoes of the great Enlightenment essays in conjectural anthropology: “It is in [the American Indians’] present condition that we are to behold, as in a mirrour [sic], the features of our own progenitors” (Ferguson 80); “the difference between the savage and domesticated man must be greater than the difference between wild animals and tame animals” (Rousseau 31). Darwin finds the recognition of a common humanity, reflected in the ancestral mirror of the savage, balked by the intuition of a difference so extreme that it may be insurmountable. His “astonishment” designates an aesthetic zero-degree: that state of cognitive blockage, of “shock nothing less than categorical in its intensity” (Schmitt 39), which announces the sublime, except that this time there is no imaginative recovery. Darwin’s astonishment sets into a revulsion that fails to modulate into wonder or rational satisfaction (see Duncan; Taussig 73-96; Beer 64-70; Schmitt 34-56).

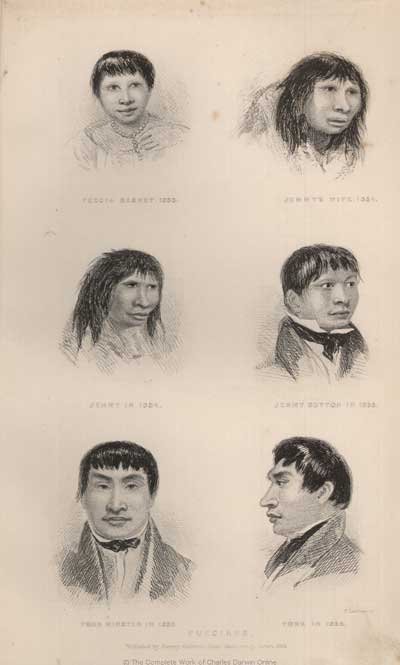

Figure 8: The Fuegians on board the Beagle, 1839 (reproduced with permission from John van Wyhe ed., The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online

Darwin did not seriously doubt that savages were fellow creatures, the types of “our progenitors.” That knowledge was what made the difference between him and them so obdurate: greater than the difference between wild and domestic animals because of, rather than in spite of, man’s “greater power of improvement.” The Fuegians have not availed themselves of that power in the two and half centuries since Drake visited their shores, and now it may be too late. “Viewing such men, one can hardly make oneself believe they are fellow-creatures, and inhabitants of the same world” (Darwin, Journal of Researches 1839: 235): the newly completed map of the world has no place for them, stranded outside the timeline of universal history. “In the Strait of Magellan looking due south from Port Famine, the distant channels between the mountains appear from their gloominess to lead beyond the confines of this world” (233). It is as though the people are ghosts, already dead, in these forests “where Death and Decay prevail” (604).

Over the next hundred years, the inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego would fall prey to the forces of settler violence and disease that Darwin observed elsewhere in his voyage. Only once do we find him imagining a scenario of Fuegian extinction, as an effect of the conjectural loss of the offshore kelp beds:

Amidst the leaves of the plant numerous fish live, which nowhere else could find food or shelter; with their destruction the many cormorants and other fishing birds, the otters, seals, and porpoises, would soon perish also; and lastly, the Fuegian savage, the miserable lord of this miserable land, would redouble his cannibal feast, decrease in numbers, and perhaps cease to exist. (1839: 305)

Darwin ascribes the prospect to a natural cause, an ecological collapse, rather than to human invaders; rather than being devoured by others, the savages devour themselves. He declines to imagine the Fuegians’ extinction as an event in human history—as a consequence, for instance, of the expansion of European interests that has brought H.M.S. Beagle to the tip of South America. They are specters of a future catastrophe, of which the cause is veiled.

Darwin recurred to his Fuegian encounter throughout his career, in a repeated pattern of recognition and rejection, inclusion and exclusion, “total recall and deliberate amnesia” (Schmitt 35). The savage marks a crux in the theory of evolution by natural selection as it comes to bear on human life. Darwin’s recollection of his primal shock keeps interfering with his rational acceptance of savages as “our progenitors,” stationed between prehuman ancestors and historical forebears. Forty years after setting sail on the Beagle, he stages the crux as (once more) a collision between scales of historical meaning—between the scientific interest proper to natural history and the local pathos of his personal history—in the conclusion of The Descent of Man:

The main conclusion arrived at in this work, namely that man is descended from some lowly-organised form, will, I regret to think, be highly distasteful to many persons. But there can hardly be a doubt that we are descended from barbarians. The astonishment which I felt on first seeing a party of Fuegians on a wild and broken shore will never be forgotten by me, for the reflection at once rushed into my mind—such were our ancestors. . . . He who has seen a savage in his native land will not feel much shame, if forced to acknowledge that the blood of some more humble creature flows in his veins. For my own part I would as soon be descended from that heroic little monkey, who braved his dreaded enemy in order to save the life of his keeper; or from that old baboon, who, descending from the mountains, carried away in triumph his young comrade from a crowd of astonished dogs—as from a savage who delights to torture his enemies, offers up bloody sacrifices, practises infanticide without remorse, treats his wives like slaves, knows no decency, and is haunted by the grossest superstitions. (689)

Darwin keeps faith with his youthful astonishment in order to harness it rhetorically, rather than merely reiterating it like a traumatic symptom. The passage invokes the savage as an affective and moral blind spot—rather than a logical or cognitive blind spot—in Darwin’s and his readers’ perspective. The Fuegians are disgusting because “such were our ancestors”: the difference between wild and civilized man is a historical phenomenon, not a biological one. Horror and shame make up the structure of feeling entailed by Darwin’s theory. They are its subjective proof. It is a key principle of natural selection, articulated in the Origin of Species, that the struggle for existence presses hardest on beings who are closely related. A particular creature thrives, it becomes a species, through the elimination of its collateral branches and ancestral types. The analytic light of Darwin’s theory thickens the darkness of that encounter on a wild and broken shore. Those who inhabit the world as our ancestors are bound to appear alien to us, as violent and obscene: only, the obscenity and violence belong to our relation with them, rather than to themselves. This Darwin’s writing knows.

published December 2012

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Duncan, Ian. “On Charles Darwin and the Voyage of the Beagle.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Barlow, Norah. “Darwin’s Ornithological Notes.” Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Historical Series 2.7 (1963): 201-78. Print.

Beer, Gillian. Open Fields: Science in Cultural Encounter. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1996. Print.

Brantlinger, Patrick. Dark Vanishings: Discourse on the Extinction of Primitive Races, 1800-1930. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2003. Print.

Browne, Janet. Charles Darwin: Voyaging. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1996. Print.

Browne, Janet and James Secord, eds. Darwin Correspondence Project. University of Cambridge, 2012. Web. 8 Nov. 2012. <http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/>.

Darwin, Charles. The Beagle Letters. Ed. Frederick Burkhardt. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2008. Print.

—. Charles Darwin’s Beagle Diary. Ed. R. D. Keynes. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988. Print.

—. Charles Darwin’s Notebooks 1836-1844. Ed. Paul H. Barrett, Peter J. Gautrey, Sandra Herbert, David Kohn, and Sydney Smith. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2008. Print.

—. Correspondence. Ed. Frederick Burkhardt et al. 16 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1985-. Print.

—. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. Ed. James Moore and Adrian Desmond. London: Penguin, 2004. Print.

—. Journal and Remarks, 1832-1836. Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle, between the years 1826 and 1836. Vol. 3. 3 vols. London: Colburn, 1839. Print.

—. Journal of Researches into the Geology and Natural History of the Various Countries visited by H.M.S. Beagle. London: Henry Colburn, 1839. Print.

—. Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World. London: Murray, 1845. Print.

—. On the Origin of Species. Ed. Gillian Beer. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

—. “Recollections of the Development of My Mind and Character.” Evolutionary Writings. Ed. James A. Secord. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. 355-425. Print.

—. Zoology Notes and Specimen Lists from H.M.S. Beagle. Ed. Richard Keynes. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000. Print.

Duncan, Ian. “Darwin and the Savages.” Yale Journal of Criticism 4 (1991): 13-45. Print.

Ferguson, Adam. An Essay on the History of Civil Society. Ed. Fania Oz-Salzberger. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1995. Print.

FitzRoy, Robert. Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836. Appendix to Volume II. London: Colburn, 1839. Print.

Humboldt, Alexander von and Aimé Bonpland. Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America, During the Years 1799-1804. Trans. Helen Maria Williams. 7 vols. 3rd ed. London: Longmans, 1822. Print.

Krasner, James. “A Chaos of Delight: Perception and Illusion in Darwin’s Scientific Writing.” Representations 31 (1990): 118-141. Print.

Lamarck, Jean Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet de. Zoological Philosophy: An Exposition with Regard to the Natural History of Animals. Trans. Hugh Samuel Roger Elliott. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2011. Print.

Lamb, Jonathan. Preserving the Self in the South Seas, 1680-1840. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2001. Print.

Leask, Nigel. “Darwin’s ‘Second Sun’: Alexander von Humboldt and the Genesis of The Voyage of the Beagle.” Literature, Science, Psychoanalysis, 1830-1970: Essays in Honour of Gillian Beer. Ed. Helen Small and Trudi Tate. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003. 13-36. Print.

Levine, George. Darwin the Writer. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011. Print.

Lyell, Charles. Principles of Geology. Ed. James A. Secord. London: Penguin, 1997. Print.

Paradis, James. “Darwin and Landscape.” Victorian Science and Victorian Values: Literary Perspectives. Eds. James Paradis and Thomas Postlewait. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1985. 85-110. Print.

Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London: Routledge, 1992. Print.

Richards, Robert J. The Romantic Conception of Life: Science and Philosophy in the Age of Goethe. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2002. Print.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Discourse on the Origins of Inequality. Trans. Franklin Phillip. Ed. Patrick Coleman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1994. Print.

Schmitt, Cannon. Darwin and the Memory of the Human: Evolution, Savages, and South America. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009. Print.

Scott, Walter. Waverley, or, ‘Tis Sixty Years’ Since. Ed. P. D. Garside. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2007. Print.

Sloan, Philip. “The Making of a Philosophical Naturalist.” The Cambridge Companion to Darwin. Eds. Jonathan Hodge and Gregory Radick. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. 17-39. Print.

Stein, Richard L. Victoria’s Year: English Literature and Culture 1836-1837. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988. Print.

Stocking, George W., Jr. Victorian Anthropology. New York: Free Press, 1987. Print.

Sulloway, Frank J. “Darwin and his Finches: The Evolution of a Legend.” Journal of the History of Biology 15.1 (1982): 1-53. Print.

Taussig, Michael. Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses. London: Routledge, 1993. Print.

Wordsworth, William. The Major Works. Ed. Stephen Gill. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Van Wyhe, John, ed. The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. N.P., 2002. Web. 8 Nov. 2012. < http://darwin-online.org.uk>.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Gowan Dawson, “On Richard Owen’s Discovery, in 1839, of the Extinct New Zealand Moa from Just a Single Bone”

Bernard Lightman, “On Tyndall’s Belfast Address, 1874″

Martin Meisel, “On the Age of the Universe”

Cannon Schmitt, “On the Publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species, 1859″