Abstract

This essay outlines the personal interactions and political events preceding John Keble’s delivery of a sermon later entitled National Apostasy to the judges gathered at Oxford for the Assize Court as a way of understanding the sermon’s significance in relation to the Oxford Movement.

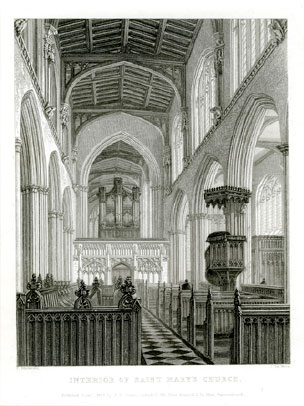

Figure 1: Interior of St. Mary’s Church, ![]() Oxford, with the pulpit from which Keble’s sermon was preached (1833 engraving; private copy, used with permission)

Oxford, with the pulpit from which Keble’s sermon was preached (1833 engraving; private copy, used with permission)

Figure 2: 1844 portrait of John Keble by George Richmond (![]() Keble College, Oxford; used with permission)

Keble College, Oxford; used with permission)

Since The Christian Year had made Keble famous outside as well as within Oxford, the Assize judges would have been gratified that Keble was to preach. However, there were only a few of them, and members of the Oxford community occupied the rest of the pews. Officiating at the service, to judge by the notation in his diary for that day, was the vicar of St. Mary’s and Oriel fellow, John Henry Newman. Newman writes, “6 Trinity Assize Sunday did duty morning and afternoon at St Mary’s Keble preached in morning Assize Sermon” (L&D 4: 5).[3] Though there is not such clear evidence that another Oriel fellow, Hurrell Froude, was also in the church, he certainly was in Oxford, and, given his excited sense of the importance of the occasion and the forcefulness of his personality, he most surely managed to be present.

Fifty years later, as Newman mused in his Apologia Pro Vita Sua on the significance of that moment, he wrote of Keble’s Assize sermon: “It was published under the title of ‘National Apostasy.’ I have ever considered and kept the day, as the start of the religious movement of 1833” (43). Or one could put it another way: these three ministers of the Church of England—Keble, Newman, and Froude—seized the opportunity given them by the occasion of the sermon to protest new developments in the long-established relationship between the Church and the State of England. A fourth figure, Edward Bouverie Pusey, who in later years was to become so prominent a figure in the Oxford Movement that its members were often dubbed Puseyites, is not included in this account. He was sympathetic to the movement soon after it commenced (L&D 4: 11) but was not involved in its very early stages.

Back Story I: Personal Connections

Unlike Keble, Newman, stressed by having over-studied, floundered when he took his University exams in 1820 and received only a pass. However, in 1822 he did brilliantly when he applied for a fellowship at Oriel—at the time Oxford’s intellectually most prestigious college—and became a fellow on April 12. He writes that he managed to stay seemingly calm when summoned to receive the congratulations of the other fellows: “I bore it till Keble took my hand, and then felt so abashed and unworthy the honour done me that I seemed desirous of quite sinking into the ground.” At dinner, he was seated beside Keble, whom he described as “more like an undergraduate than the first man in Oxford—so perfectly unassuming and unaffected in his manner” (L&D 1: 134).

Keble on his side, however, did not initially see the extremely shy new fellow as a potential friend. Through family tradition and personal conviction, Keble subscribed to an Anglicanism that looked to the seventeenth-century model, whose ideal envisioned a divinely appointed ruler acting as both devout son and temporal governor of the church’s bishops. Newman’s “bourgeois” background as son of a London banker, along with the intense but also individualistic and evangelical nature of his spirituality, distanced him from Keble. That evangelicalism became tempered fairly quickly when Newman came under the influence of theologically liberal fellows at Oriel called “the Noetics” (Apologia 20-21), but in Keble’s opinion, that change was decidedly not an improvement.[4]

Hurrell Froude, who had Keble as his tutor when he came to Oriel in 1821 and was himself a fellow after 1824, eventually brought Keble and Newman together, but for several years he shared Keble’s distrust of Newman. Handsome, charismatic (to those at least who did not find him overbearingly opinionated), and aristocratic, Froude, like Keble, was the son of an Anglican clergyman, but his views were even more radically conservative than his tutor’s: influenced by Romantic medievalism, Froude’s spirituality leaned in the direction of Roman Catholic belief and practice, though stopping short of any allegiance to the Pope (Apologia 34-35). Until the winter term of 1826 during which they both became college tutors (Ker 27), Newman and Froude also had little to bring them together. Yet at that point Newman already showed that he experienced the charisma of Froude’s extraordinary personality. After Froude became an Oriel tutor on 31 March 1826, Newman described him to his mother as “one of the acutest and clearest and deepest of men” (L&D 1: 280), but by December of the same year he risked a quarrel by calling Froude to his face a “red-hot” high churchman (Froude 59). On his side, Froude wrote to his archdeacon father on 30 November 1826: “Newman has foiled my analytical skill. I cannot make him out at all, but have got far enough to see that he is not my sort” (qtd. in Brendon 71). From a person of Froude’s upper-class temper, nothing further need be said. Their comments on both sides intimate, nonetheless, that each found the other an interesting challenge. Their propinquity at Oriel and their shared duties as tutors necessarily brought them often together, and, before long, as Newman’s own statement in the Apologia makes clear (35), he had come to subscribe to Froude’s way of thinking and to disassociate himself from his old liberal mentors. At the same time, Froude had succeeded in convincing Keble that Newman was a man whose views could now be trusted, and the three embarked in 1828 on their first shared politico-religious campaign: the ousting of Robert Peel as Member of Parliament for Oxford because of the stand he was taking on the issue of Catholic Emancipation.

Back Story II: Political Events

That year, 1828, brought the signal of an imminent and radical change in a relationship between Church and State first enunciated in the 1534 Act of Supremacy that declared Henry VIII to be head of the Church of England: the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts promulgated after the Restoration of Charles II. Aimed particularly at discouraging Protestant Dissent, the Corporation Act of 1661 stipulated that all mayors and officials in municipal corporations must receive the sacrament of Holy Communion within the rites of the Church of England as well as take an oath accepting the monarch’s supremacy in both church and state. The 1673 Test Act extended that demand to all holders of civil and military offices and places of trust, including, of course, Parliament. Under that arrangement the Crown could be assured of its authority over the established church, while the clergy could view monarch and Parliament as a lay synod that provided for its worldly needs but was subject to its spiritual rule. Left without representation, along with many other privileges, however, were all dissenting Protestant sects and Roman Catholics as well as atheists and Jews. All that changed in the spring of 1828, under the Duke of Wellington’s Tory administration, with Robert Peel, the Home Secretary, as second in command: on May 9, the Sacramental Test Bill, rightly seen as a prelude specifically to Catholic emancipation, repealed the Test and Corporation Acts (cf. Michie).

Peel had been an Oxford favorite ever since November 1808, when he was Keble’s predecessor in attaining a double first. He entered the House of Commons soon thereafter and from 1812 to 1818 served under Lord Liverpool’s Tory administration as chief secretary for Irish administration. There he so strongly (and effectively) favored the Protestant ascendancy and resisted Catholic claims for political rights that he came close to a violent clash with the Irish Catholic political leader, Daniel O’Connell, who dubbed him “Orange Peel” (“Robert Peel”). Oxford, on the other hand, so approved of Peel’s Irish activities that he was invited to become its member of the House of Commons in recognition of his “services to Protestantism.” When, therefore, from political expediency and under threat of an Irish Catholic insurrection, Peel reluctantly agreed to a repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts and accepted the upcoming inevitability of Catholic political emancipation, he offered to vacate his Oxford seat (Prest). Sir Robert Inglis, also a Tory but an opponent of Catholic emancipation and a strong supporter of the Church of Ireland, then put himself into the running as Oxford’s representative, and the university-wide Convocation had its opportunity to make a choice between the two men.[5]

Froude may well have stirred up both Keble’s and Newman’s energies for this fight, but at the crucial time of the campaign he suffered from a racking cough, an early sign of the tuberculosis that would end his life in 1836. Keble and Newman, therefore, took over much of the canvassing in what turned out to be a precedent for the Tractarian enterprise that began in 1833. In both they used a similar strategy: they networked with colleagues both past and present, using the mail delivery system and the printing services available to them through their college connection, to contact those former fellows who were now serving in parishes throughout the country.

The John Davison folder in the Keble Archive at Keble College gives an excellent example of how the operation worked. Davison, fifteen years Keble’s senior, had been a distinguished member of Oriel at the time that Keble became a fellow. Although Davison numbered among the Noetics, Keble’s letters to him show that the two were congenial colleagues, even friends. They continued to be so after 1817, when Davison, having been presented with a vicarage, gave up his fellowship, married, and then went on to other clerical honors and assignments (Blaikie). To Davison, then, among a number of other colleagues, Keble wrote from Fairford on 18 February 1829. He begins, “Having felt it my duty to write & print what I send you with this, I need not say that it will give me great pleasure if I find you concurring with me in thinking Sir Robert H. Inglis the right person to be returned for the University.” With the letter came this printed message (Keble Archive AD 1/50):

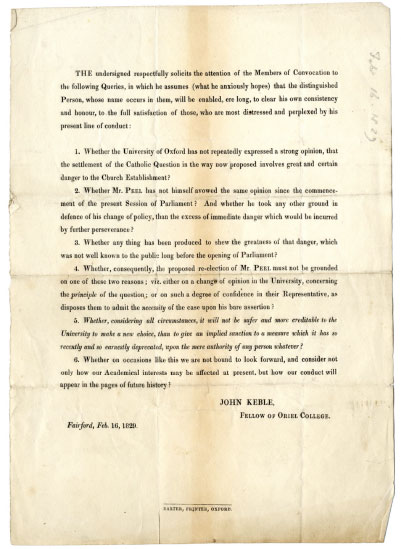

Figure 3: Printed circular opposing the 1829 election of Robert Peel (Keble Archive AD 1/50, Keble College, Oxford; used with permission)

Keble’s six queries in fact make a statement that the settlement of the Catholic question “in the way now proposed” puts the church establishment in grave danger (Keble Archive AD 1/50). Peel had in the past agreed that such was the case, as had the university. Thus, what particularly angers Keble is that Peel changed his position only because he feared an “excess of immediate danger” to himself politically if he continued to stand by what for years he professed to believe (1/50). Newman expresses the same opinion more colloquially in a letter dated 6 February 1829: “It is not pro dignitate nostrâ, to have a Rat our member [of Parliament]” (L&D 2: 118). Therefore, Keble judges, it will be “safer and more creditable to the University to make a new choice” (1/50).

Meanwhile, as is clear from Newman’s letters during those busy days, he also was writing to friends about this topic, and enclosing Keble’s printed statement as a way of adding the moral force of Keble’s opinion to his own argument. He wrote, for instance, to Samuel Rickards, a friend and former Oriel fellow now a curate in ![]() Ulcombe,

Ulcombe, ![]() Kent (Boase): “Is it not noble in modest Keble to come forward with his own fair name on this occasion? . . . . I feel and assent to his view entirely” (L&D 2: 123). Froude’s health may have prevented him from being as active a letter writer as the others, but Newman’s diary entries as well as his letters show that the two had many meetings that must have in part been strategy sessions.

Kent (Boase): “Is it not noble in modest Keble to come forward with his own fair name on this occasion? . . . . I feel and assent to his view entirely” (L&D 2: 123). Froude’s health may have prevented him from being as active a letter writer as the others, but Newman’s diary entries as well as his letters show that the two had many meetings that must have in part been strategy sessions.

Newman’s jubilant account of the outcome, written to his mother on 1 March 1829, clarifies the purpose of these letters. Former fellows still had voting rights in the Convocation but had to be present for the vote. Ten days earlier, when there seemed little chance of Peel’s defeat, the trio had been concerned about putting colleagues “to the expense of coming up,” and had considered simply voting themselves “though the majority against us might be many hundreds,” but had decided nonetheless to make the attempt through circulating Keble’s six-point protest. Given the outcome, Newman sees that holding back from that effort would have been “inexcusable,” for it would have “deprived our country friends of the opportunity of voting” (L&D 2: 126). The triumvirate’s efforts in mustering up friends this way was undoubtedly not the only reason for Peel’s defeat, but Newman’s glee over the outcome seems justified: Inglis won 755 votes to Peel’s 609, and a number of those 755 votes were cast as a result of the trio’s letter campaign. This was a memorable lesson in what constituted effective strategy.

As was expected, however, Oxford’s rejection of Peel as its representative had no effect on the final outcome: Peel returned to Parliament nonetheless from the “pocket borough” of ![]() Westbury, and the Catholic Emancipation Bill passed. Moreover, the divisions within the Tory party over its passage led to the fall of the Duke of Wellington’s administration. The Whigs, under the leadership of Earl Grey, swept into power and, despite strong opposition, succeeded in enacting the Great Reform Bill of 1832; among other needed reforms, it considerably increased the number of men in the population entitled to vote. That done, the government embarked on further changes, among them a restructuring of the Church of Ireland.

Westbury, and the Catholic Emancipation Bill passed. Moreover, the divisions within the Tory party over its passage led to the fall of the Duke of Wellington’s administration. The Whigs, under the leadership of Earl Grey, swept into power and, despite strong opposition, succeeded in enacting the Great Reform Bill of 1832; among other needed reforms, it considerably increased the number of men in the population entitled to vote. That done, the government embarked on further changes, among them a restructuring of the Church of Ireland.

In 1690, with English power over ![]() Ireland firmly established, Parliament created twenty-two Church of Ireland bishoprics supported by tithes levied on all Irish subjects of the Crown, whatever their religious affiliation. Since the great majority was and remained Roman Catholic, this added tax burden created ongoing and rising resentment as the centuries passed and became untenable once the Irish had been allowed a presence in the English Parliament. Early in 1833, therefore, the Whig government put forward the Irish Church Temporalities Bill; it proposed to reduce the number of bishoprics and archbishoprics by almost half—from twenty-two to twelve—and to remove those of the parish clergy who had no parishioners.

Ireland firmly established, Parliament created twenty-two Church of Ireland bishoprics supported by tithes levied on all Irish subjects of the Crown, whatever their religious affiliation. Since the great majority was and remained Roman Catholic, this added tax burden created ongoing and rising resentment as the centuries passed and became untenable once the Irish had been allowed a presence in the English Parliament. Early in 1833, therefore, the Whig government put forward the Irish Church Temporalities Bill; it proposed to reduce the number of bishoprics and archbishoprics by almost half—from twenty-two to twelve—and to remove those of the parish clergy who had no parishioners.

In other words, just as Keble and his associates had feared, a House of Commons now containing representatives who were not members of the United Church of England and Ireland was in a position to pass a law that demonstrated its political control over this ecclesiastical institution. Erastian theory—so called because it was attributed to a seventeenth-century German physician named Erastus—that the state should have supremacy over ecclesiastical affairs had won the day.

When this occurred, the two more activist members of the group were in ![]() Naples, on their way to

Naples, on their way to ![]() Rome (L&D 3: 224). Newman had accepted an invitation from Hurrell and his father, Archdeacon Froude, to come to

Rome (L&D 3: 224). Newman had accepted an invitation from Hurrell and his father, Archdeacon Froude, to come to ![]() Italy with them when Froude’s troubling cough proved to be the onset of tuberculosis, and he was advised of the necessity of escaping the English winter. From Rome, they had only limited opportunity to follow events, but Newman’s letter to his sister Jemima, dated 20 March 1833, shows that he and Froude already had campaign plans, so to speak, and were jubilant that again they, as comparative unknowns, would be reinforced by Keble’s voice and presence: “We are at present in good spirits about the prospect of the Church. We find Keble at length roused and (if once up) he will prove a second St Ambrose—others too are moving—so that wicked Spoliation Bill is already doing service, no thanks to it” (L&D 3: 264). By using the term “spoliation,” with its violent connotations of pillage, plundering, and unlawful seizure of property, Newman roundly conveys his response to the Irish Church Temporalities Bill. His mention of St. Ambrose puts the decisions being made about the church in Ireland into a broad historical context.

Italy with them when Froude’s troubling cough proved to be the onset of tuberculosis, and he was advised of the necessity of escaping the English winter. From Rome, they had only limited opportunity to follow events, but Newman’s letter to his sister Jemima, dated 20 March 1833, shows that he and Froude already had campaign plans, so to speak, and were jubilant that again they, as comparative unknowns, would be reinforced by Keble’s voice and presence: “We are at present in good spirits about the prospect of the Church. We find Keble at length roused and (if once up) he will prove a second St Ambrose—others too are moving—so that wicked Spoliation Bill is already doing service, no thanks to it” (L&D 3: 264). By using the term “spoliation,” with its violent connotations of pillage, plundering, and unlawful seizure of property, Newman roundly conveys his response to the Irish Church Temporalities Bill. His mention of St. Ambrose puts the decisions being made about the church in Ireland into a broad historical context.

The allusion arises from Newman’s ongoing study of the Fathers of the Church as his focus for the grounds of both orthodox doctrine and church government. Newman sees a precedent for contemporary events in the fourth-century confrontation between St. Ambrose (c. 340-397 CE), then Bishop of ![]() Milan, with the Dowager Empress Justina over the Arians’ right to appropriate a church in his diocese for their worship—an argument that Ambrose won because he had strong popular support.[6]

Milan, with the Dowager Empress Justina over the Arians’ right to appropriate a church in his diocese for their worship—an argument that Ambrose won because he had strong popular support.[6]

This involvement on Newman’s part with events unfolding in England and Ireland stopped abruptly, however, in the months that followed. When the Froudes began the journey back to England on 9 April, Newman turned south to ![]() Sicily. There in mid-May he very nearly died of typhoid fever and arrived back in England on 9 July, still suffering from the after-effects of his illness and the strain of the arduous return journey. But, as we have seen, he was there in St. Mary’s on 14 July to hear the results of the efforts he and Froude had made to “rouse up” Keble for this protest.

Sicily. There in mid-May he very nearly died of typhoid fever and arrived back in England on 9 July, still suffering from the after-effects of his illness and the strain of the arduous return journey. But, as we have seen, he was there in St. Mary’s on 14 July to hear the results of the efforts he and Froude had made to “rouse up” Keble for this protest.

What Keble Said

Keble took as text for his sermon the prophet Samuel’s final exhortation to the Jewish people after acceding to their demand for having a king, as did other surrounding nations, instead of the ad hoc leadership of unelected judges along with God’s guidance and admonishment through his prophets. More in sorrow than in anger about a decision he deplores, the prophet says that he will never cease his prayers for them, but he will not rescind his right and duty to “teach you the good and the right way” (KJV, 1 Sam. 12.23). In the same way, Keble stands before the Assize judges, who serve as representatives of an erring national government, to instruct them in the sinful error of the country’s recent choices.

Keble’s summary of this moment in Jewish history—which he sees as the beginning of a process that ends in the Babylonian captivity—conveys also his view of its relevance to contemporary events: “[T]his first overt act, which began the downfall of the Jewish nation, stands on record, with its fatal consequences, for a perpetual warning to all nations, as well as to all individual Christians, who, having accepted God for their King, allow themselves to be weary of subjection to Him, and think they should be happier if they were freer, and more like the rest of the world” (National Apostasy).[7] The implicit parallel is between the Jewish desire for a monarchy like that of neighboring states and the push of contemporary liberal thinking toward acceptance of an essentially secular state with administrative power, nonetheless, over the Church of England. But does this mean that Keble believes England to have been a theocracy since the time of the Tudors, or that he would envision theocracy as his ideal?

As S. A. Skinner has pointed out, the best place in which to find Keble’s “definitive Tractarian expression . . . of the relationship between Church and State” (36) is his very lengthy 1839 review of William Gladstone’s The State in its Relations with the Church published in 1838. Gladstone attempts to re-establish concord after the strains of the previous decade through a marital metaphor that Keble quotes verbatim: “The Church . . . is united [to the State] as a believing wife to a husband who threatens to apostasize; and as a Christian wife so placed, would act, with patience, and love, and tears, and zealous entreaties . . . so the Church must struggle even now, and save not herself but the State from the crime of a divorce” (State 6). Since, however, under the law of “coverture” operative in England at the time, a husband and wife were one person and that person was the husband, Gladstone’s metaphor leaves the Church powerless with respect to the State save as an amorphous moral influence, and Keble rejects that position. (On coverture, see Kelly Hager, “Chipping Away at Coverture: The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857.″) Or rather, he returns the marital metaphor to its traditional use: the Church is the spouse not of the State but of Christ. Then, calling upon the prophet Isaiah, he uses a passage that says of ![]() Israel, “And kings shall be thy nursing fathers and their queens thy nursing mothers” (KJV, Isa. 49.23) to extend the metaphor so that heads of states have only such power over the Church as palace officials might when overseeing the welfare of a monarch (25). The Church’s power, by contrast, resides in Christ’s establishment of her through the mission given to his Apostles and transmitted through the Apostolical Succession of Christian bishops ever since. The nomination of bishops “exclusively by the Crown,” therefore, as seen in the Irish Church Temporalities Bill, is an “encroachment by our nursing fathers” (43), as he names it in his Gladstone review or, as he says in the National Apostasy sermon, “an infringement on Apostolical Rights.”

Israel, “And kings shall be thy nursing fathers and their queens thy nursing mothers” (KJV, Isa. 49.23) to extend the metaphor so that heads of states have only such power over the Church as palace officials might when overseeing the welfare of a monarch (25). The Church’s power, by contrast, resides in Christ’s establishment of her through the mission given to his Apostles and transmitted through the Apostolical Succession of Christian bishops ever since. The nomination of bishops “exclusively by the Crown,” therefore, as seen in the Irish Church Temporalities Bill, is an “encroachment by our nursing fathers” (43), as he names it in his Gladstone review or, as he says in the National Apostasy sermon, “an infringement on Apostolical Rights.”

In the face of such encroachment, as we shall see, Keble, along with Newman and Froude, brooded upon the radical possibility of disestablishment, but in the sermon itself, the tone of his response has parallels with the one suggested by Gladstone. In the face of the state’s Erastian overreaching, Keble’s conclusion echoes his initial text from Samuel by advocating: “earnest INTERCESSION with God” on behalf of a misguided nation and “grave, respectful, affectionate REMONSTRANCE” with the nation itself (National Apostasy).

The peaceable tone with which Keble ends his argument reveals the core of his response to the inflammatory events of the time. If Newman took his example from the saintly but determined Ambrose and Froude from his hero Thomas a` Becket, martyred but victorious over Henry II, Keble remained centered in his allegiance to such sixteenth-century divines as Richard Hooker, who worked within parameters congenial to the state to establish those traditionally based doctrines and attendant rituals that are “the peculiar happiness of the Church of England” (“Advertisement” to The Christian Year.)

The Outcome

To judge by its immediate impact, Keble’s sermon was a non-event. The Irish Church Temporalities Bill became law on 14 August, and although Sir Robert Inglis had risen loyally in protest (Hansard Archive, House of Commons Debate, 6 May 1833), the thirty Anglican bishops who sat in the House of Lords acquiesced in its passage as they had in the earlier pieces of legislation. After giving the sermon, Keble returned to Fairford, and Newman’s brush with death in Sicily had drained him of energy. He confesses in a diary account of the previous months written on 6 December 1833, that in the wake of the sermon, “I was lowspirited about the state of things and thought nothing could be done” (L&D 4: 10). Nonetheless, that diary entry begins with the date of Keble’s Assize sermon, and so from very early on, and not just at the time of writing the Apologia, Newman saw the sermon as a watershed event. Also, as the diary shows, Newman quickly gathered strength for the cause. He continues: “I wrote to Froude (I think) who was in ![]() Essex—and to Keble—urging to the latter the gift we had committed to us in being in Oxford, which was a kind of centre and traditionary source of good principles. On his doubting about it, I wrote him word, he might join it or not—but the League was in existence—it was a fact, not a project” (10). The next sentence in the diary carries an amusing admission that “the League” was actually a fiction concocted for Keble’s benefit: “Froude and I were the only two members at that moment” (10).

Essex—and to Keble—urging to the latter the gift we had committed to us in being in Oxford, which was a kind of centre and traditionary source of good principles. On his doubting about it, I wrote him word, he might join it or not—but the League was in existence—it was a fact, not a project” (10). The next sentence in the diary carries an amusing admission that “the League” was actually a fiction concocted for Keble’s benefit: “Froude and I were the only two members at that moment” (10).

In fact, however, there were others involved in this groundswell of protest. Indeed, Froude was in Essex attending an ad hoc strategy conference held in the rectory of Hugh James Rose, who had studied for the ministry at ![]() Cambridge and who had already forwarded the cause of those who favored High Church as opposed to evangelical or liberal principles by editing the British Critic. However, in essence Newman was right: among the five churchmen present at this meeting, Froude was the only one who favored not a top-down association of churchmen who would lobby for their cause but a radical grassroots movement that would transform the Church of England through a return to traditional principles and practices. Thus, the Essex meeting came to an impasse, but by August Newman and Froude, having brought Keble on board, had set their former strategy in motion: it would involve the writing of personal letters to establish a communications network to facilitate the dissemination of “tracts.” Newman’s language as he urges Keble to further action shows how much the old anti-Peel campaign was still on his mind as he turned to this new effort. In a letter to Keble dated 5 August 1833, Newman writes: “Do let us agree on some plan about writing letters to our friends, just as if we were canvassing. . . . I would not mind writing (as in an election) to persons even whom I knew very little of” (L&D 4: 21). Piers Brendon describes their activity with the image of a troika: “[D]uring the summer and autumn of 1833 the course of the Movement was determined by a triumvirate consisting of Newman, who held the reins, Keble, who provided the motive power, and Froude, who wielded the whip and yelled directions” (128).

Cambridge and who had already forwarded the cause of those who favored High Church as opposed to evangelical or liberal principles by editing the British Critic. However, in essence Newman was right: among the five churchmen present at this meeting, Froude was the only one who favored not a top-down association of churchmen who would lobby for their cause but a radical grassroots movement that would transform the Church of England through a return to traditional principles and practices. Thus, the Essex meeting came to an impasse, but by August Newman and Froude, having brought Keble on board, had set their former strategy in motion: it would involve the writing of personal letters to establish a communications network to facilitate the dissemination of “tracts.” Newman’s language as he urges Keble to further action shows how much the old anti-Peel campaign was still on his mind as he turned to this new effort. In a letter to Keble dated 5 August 1833, Newman writes: “Do let us agree on some plan about writing letters to our friends, just as if we were canvassing. . . . I would not mind writing (as in an election) to persons even whom I knew very little of” (L&D 4: 21). Piers Brendon describes their activity with the image of a troika: “[D]uring the summer and autumn of 1833 the course of the Movement was determined by a triumvirate consisting of Newman, who held the reins, Keble, who provided the motive power, and Froude, who wielded the whip and yelled directions” (128).

It is outside the scope of this essay to describe the content of the tracts and other related publications that brought the message of what came to be known as the Oxford Movement to every corner of England and to the worldwide Anglican Communion, including the American Episcopal Church. Newman was also right in thinking that the strength of the movement in Oxford and also Cambridge, the nation’s centers for religious study, would greatly influence future clerics. But at this initiatory moment a single letter from Keble, again to John Davison, makes it possible to watch the scattering of the grass seed that was to have such rapid future growth. Davison’s response to the earlier request that he vote against Peel had been disappointing, for though deeply pained to find himself in disagreement with his old friend, Davison felt that “[o]n grounds of religion & justice” (Keble Archive AD 1/50) he must favor Catholic Emancipation. Nonetheless, Keble wrote him again on 13 August 1833, from Oriel College, and so in all probability from Newman’s room, which had become campaign headquarters. He enclosed several copies of National Apostasy, one for Davison and others for further dissemination among friends. Then, in the letter’s central paragraph, Keble outlines the “scheme” that he and “some of my friends here” have devised:

They think it might be worth while to try, how many friends of the Church of England might be brought to associate & subscribe for these two definite purposes: viz. The diffusion of eight notions, with regard to the Apostolical commission of the Clergy; & the protection of the Prayer Book from hasty or profane interference – We conceive, for instance, that a series of cheap tracts for the poor, enabling them to imagine a little more than they can at present of Primitive times, might be of the greatest service to them, in preserving them from Schism under certain contingencies, which appear to become less improbable daily. (Keble Archive AD 1/50)

Keble is vague at that point about what the possible “Schism” might entail, but the last sentences of the paragraph offer some further insight into what he is getting at: the possible disestablishment of the Church of England—in short, on radically conservative rather than liberal grounds, the separation of church and state:

The State has been so long considered by all sorts of people as our real & practical bond of union, that we should be in danger of falling quite apart from one another if any thing should happen to separate us from it. Is it not our duty, in a quiet way, to prepare ourselves for such a contingency, & might not such a project as I have hinted at be so managed, as to have that effect, without wantonly causing alarm or jealousy? (Keble Archive AD 1/50)

Mark Chapman on this and other evidence judges that “Although it would be misleading to call Keble a political radical . . . there is a sense, possibly ironic, in which he prepared the way for a slow but inexorable move toward the independence of the Church and the freedom of religion in a pluralist State,” and he did so as “the senior figure of one of the most unlikely bands of revolutionaries of all time” (50).

No schism within the Church of England occurred, and clerical appointments remained under Parliamentary oversight. But within a church already noteworthy for its ability to contain differing religious views and practices, “The religious movement of 1833,” in Newman’s phrase (Apologia 43), began a process that re-shaped for many among clergy and laity their sense of the church’s history within the Christian tradition and their experience of both liturgy and sacrament.

Figures 4 and 5: 14 August 1833 letter from John Keble to John Davison (Keble Archive AD 1/50, Keble College, Oxford; used with permission)

published May 2013

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Materials from the Keble Archive as well as the Keble portrait by George Richmond are reproduced with the kind permission of the Warden and Fellows of Keble College. My thanks go to the Archivist of Keble College, Robert Petre, for all his assistance, and I am much indebted also to the two BRANCH reviewers for their helpful suggestions and to Laura Eidam, my copy-editor, for her care, patience, and insight.

HOW TO CITE THIS BRANCH ENTRY (MLA format)

Gelpi, Barbara Charlesworth. “14 July 1833: John Keble’s Assize Sermon, National Apostasy.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [Here, add your last date of access to BRANCH].

WORKS CITED

Blaikie, W. G. “John Davison.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford UP, 2004-13. Web. 3 Sept. 2012.

Blair, Kirstie, ed. John Keble in Context. London: Anthem, 2004. Print.

Boase. G. C. “Samuel Rickards.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford UP, 2004-13. Web. 20 Aug. 2012.

Brendon, Piers. Hurrell Froude and the Oxford Movement. London: Elek, 1974. Print.

Butler, Perry. “John Keble.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford UP, 2004. Web. 31 Aug. 2012.

Chapman, Mark. “John Keble, National Apostasy, and the Myths of 14 July.” Blair 47-57.

“Convocation.” Def. 4a. Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford UP, 2013. Web. 5 Jan. 2013.

Froude, Richard Hurrell. Remains of the Late Reverend Richard Hurrell Froude. M.A. Vol. 1. London: J. G. & F. Rivington, 1838. Print.

—. The Christian Year: Thoughts in Verse for Sundays and Holydays Throughout the Year. London: Ward, Lock, and Tyler, n.d. Print.

—. National Apostasy. 1833. Ed. Arthur Burns. UK: Nolitho, 2012. Print, Kindle ebook. Project Canterbury. N.p., n.d. Web. 1 May 2012.

—. The State in its Relation with the Church. Oxford and London: James Parker and Co., 1869. Lexington: BiblioLife, 2012. Print.

Hansard Archive: 1803-2005. Web. 5 Sept. 2012.

Ker, Ian. John Henry Newman: A Biography. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988. Print.

“Liberal.” Def. A, 4a. Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford UP. 2013. Web. 8 Jan. 2013.

Newman, John Henry. Apologia Pro Vita Sua. Ed. Martin J. Svaglic. London: Oxford UP, 1967. Print.

—. The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman. Ed. Ian Ker and Thomas Gornall. S.J. Vols. 1-4. New York: Oxford UP, 1978-80. Print.

—. “What Does St. Ambrose Say About It?” Historical Sketches, Volume I. Newman Reader. Web. 11 Jan. 2013.

Prest, John. “Sir Robert Peel.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford UP, 2004-13. Web. 14 Aug. 2012.

“Robert Peel: Biography.” Spartacus Educational. Spartacus Educational, n.d. Web. 14 Aug. 2012.

Skinner, S. A. “‘The Duty of the State’: Keble, the Tractarians, and Establishment.” Blair 33-46.

RELATED BRANCH ARTICLES

Miriam Burstein, “The ‘Papal Aggression’ Controversy, 1850-52″

Laura Mooneyham White, “On Pusey’s Oxford Sermon on the Eucharist, 24 May 1843”

ENDNOTES

[1] Those involved in the events of 14 July 1833 would have taken only a negative pleasure in the irony that the day marked the overthrow of the ![]() Bastille, a symbol of despotic royal power. For Newman at the time, for instance, “the success of the Liberal cause” epitomized by the French Revolution so annoyed him that in December 1832, he “would not even look at the tricolour” of a French vessel seen on his voyage to Italy (Apologia 42). Far from trying to overthrow an “ancien régime,” they were intent on restoring aspects of ancient faith and practice that they saw as at risk in the Anglican Communion. For that very reason, however, the date has ironic significance.

Bastille, a symbol of despotic royal power. For Newman at the time, for instance, “the success of the Liberal cause” epitomized by the French Revolution so annoyed him that in December 1832, he “would not even look at the tricolour” of a French vessel seen on his voyage to Italy (Apologia 42). Far from trying to overthrow an “ancien régime,” they were intent on restoring aspects of ancient faith and practice that they saw as at risk in the Anglican Communion. For that very reason, however, the date has ironic significance.

[2] Perry Butler in the 2004 edition of the Dictionary of National Biography describes The Christian Year as “probably the widest selling book of poetry in the nineteenth century.”

[3] L&D is short for The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman.

[4] An admiring and perhaps also envious Oxford used the term “Noetics”—i.e. “Intellectuals,” from the Greek word, ηους, “mind”—to refer to fellows at Oriel such as Edward Hawkins and Richard Whately. These men were characterized by a theological liberalism defined by the OED as seeing “the possibility, even advisability, of dispensing with or changing traditional views and concepts,” a view that was anathema to Keble.

[5] The OED’s entry #4a on “convocation” gives the word’s meaning within ![]() Oxford University’s system of governance as “the great legislative body of the University, consisting of all qualified members with the degree of M.A.”

Oxford University’s system of governance as “the great legislative body of the University, consisting of all qualified members with the degree of M.A.”

[6] Later in 1833, the British Magazine published an essay by Newman on this topic entitled “What Does St. Ambrose Say About It?” In the preamble to that discussion, Newman underscores its contemporary relevance and concludes that, when betrayed by the government, the clergy must “look to the people” (341).

[7] The text of Keble’s sermon is available on the Project Canterbury website, but it does not contain Keble’s “Advertisement,” dated 22 July 1833, which prefaced the copy circulated after the sermon was delivered. That is available in the edition edited by Arthur Burns.